More information on this discovery and exploration of the wrecks of U-550 and Pan Pennsylvania can be found here:

|

The Elusive Wolf: The Discovery of U-550

| This article was originally published in issue 31 (2013) of Wreck Diving Magazine. |

|

The boat's name was Tenacious�certainly an apt label for the vessel and crew who found a long-lost German submarine, one that had eluded searchers for decades. The date was July 23, 2012�68 years, three months and eight days since the U-boat had been bested in a brief, violent contest between combatants in the waters south of Nantucket Island. The finders were veteran wreck divers who had dreamed of locating and exploring this particular vessel for years. The submarine was U-550, one of the last undiscovered German submarines sunk off the American coast during the Second World War, and she was believed to lie in diveable waters�but barely. | |

|

World War II's oceanic battles left a trail of twisted, broken steel strewn across the sea floor off America's Eastern Seaboard. By tonnage, number of vessels sunk, lives lost or any other quantifiable measure, the majority of that steel wreckage was overwhelmingly from the Allied side of the conflict. Within the boundaries of the Eastern Sea Frontier, stretching from the Canadian border to Florida, there were 114 Allied ships sunk versus 11 U-boats between 1942 and 1945. Of those 11 submarines, six have been located (U-85, U-215, U-352, U-701, U-853 and U-869) and are reachable by divers, while three are believed to lie off the edge of the continental shelf (U-521, U-548 and U-576)�too deep for scuba divers. The location of the remaining two (U-550 and U-857) has remained a mystery, and both have had their share of hunters. | |

|

April 16, 1944: The war to end all wars had been raging off the American coast for more than two years. What had begun as a near rout on Allied shipping in the six months following Pearl Harbor had reversed course, and any U-boat venturing into American coastal waters now quickly found itself in severe peril. There may be no better example of how much the United States' anti-submarine defenses had matured during the war than the quick and fatal retribution rained upon U-550. | |

|

A long range, type IXC/40 submarine, U-550 left Kiel on her first and last war patrol on February 6, 1944, under the command of 26-year old Kapit�nleutnant Klaus H�nert. Passing North of the Faroe Islands after a brief stop in Kristiansand, Norway, she settled in south of Iceland and spent two weeks reporting mid-Atlantic weather to Germany. On February 22, while traveling on the surface, the new boat got its first taste of combat when a Catalina flying boat patrolling out of Iceland found her. The PBY unleashed a barrage of machine gun fire, killing one German and severely wounded a second, and dropped four depth charges accurately enough to hole a fuel tank and wash another sailor overboard. Shaking off the attack, H�nert finished his weather reporting assignment on March 17 and headed for the American coast, hoping for more satisfying action. | |

|

Sixty-four days after leaving Kiel, U-550 neared the Long Island coastline and received orders to move inshore of the 100 fathom line. After eight days of unproductive hunting, U-550 finally heard the sounds of a convoy passing overhead early on April 16. Bringing the boat up to periscope depth, H�nert found himself smack in the middle of a juicy convoy of nearly 20 tankers heading east. Singling out the massive 11,000-ton Pan Pennsylvania, H�nert fired three torpedoes before quickly diving deep, putting the boat on the bottom at 90 meters in an attempt to hide from the escorts he knew would soon be looking for him. Submerged in the silence of the deep ocean, the Germans heard three quick explosions and correctly assumed they had hit their target. | |

|

On board Pan Pennsylvania, Chief Radio Operator Morton Ralphelson had just sat down to breakfast after a four-to-eight a.m. watch. As he bit into the first good biscuit he had on that ship thinking, "boy this is going to be a great trip!" a torpedo slammed into the ship's number eight tank, knocking all the dishes in the wardroom to the floor. The tanker quickly took a 30° list to port but, despite her cargo of flammable gasoline, didn't immediately catch fire. Captain Delmar Leidy ordered the ship swung hard to port, away from the remainder of the convoy, which had just begun to move into formation. Some of the crew, less than thrilled to be aboard a torpedoed tanker full of gasoline, attempted to launch one of the lifeboats while the ship was still under way. The small boat capsized as it hit the water, spilling everyone aboard into the sea where they were drowned. Meanwhile, a below-decks inspection revealed gasoline had leaked into the bilges and was feeding a rapidly spreading fire in the engine room. Captain Leidy now had no choice but to order the remainder of the crew to abandon ship. | |

|  |

| U-550 comes to the surface after being depth charged (left); men crowd the submarine's conning tower as the Pan Pennsylvania burns in the distance(right, both National Archives) | |

|

Three of the convoy's escorts converged on the torpedoed tanker: USS Joyce and USS Peterson, both manned by Coast Guard crews, began picking up survivors, while the Navy-crewed USS Gandy stood by as a screen against further submarine attack. Just as the last of the tanker's crew were rescued from the sea, Joyce picked up a solid sound contact and moved in to attack, dropping a pattern of eleven depth charges. Seven minutes later the offending U-boat burst to the surface, bow first, where the destroyer escorts greeted her with a hailstorm of gunfire. USS Gandy, finding herself well positioned for an attack run, moved in to ram the intruder and struck her near the stern. After three minutes of blistering gunfire the Allied sailors thought they saw the submarine fire a white flare as a sign of surrender and ceased their onslaught. Until then the German submariners had been unable to abandon their craft due to the heavy fire, but now began pouring out of their rapidly settling boat and crowded onto the conning tower, then jumped into the sea. Joyce once again began picking up survivors, but this time the men were German, and all watched as U-550 sank stern first 30 minutes after being blown to the surface. Twelve of the U-boat's crew were picked up, including Kapit�nleutnant H�nert, and transported to Londonderry, Ireland, to become prisoners of war. Of the 81 men on board Pan Pennsylvania, 56 survivors were picked up, but 25 men were lost, almost all in the fatal lifeboat incident. | |

|

With the war's end the maritime carnage that had taken place off the American coast faded into obscurity. It was only fishermen, and later scuba divers, who were interested in the twisted war wreckage that lay hidden beneath the sea. Diver's interest in finding U-550 seems to have first surfaced with the dawn of the "tech diving" revolution in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Reportedly sunk in 300+ feet of water, the availability of trimix would now make diving the lost warship possible�if she could be located. (I speculated about finding and diving both Pan Pennsylvania and U-550 in the last chapter of my 1993 book, Beyond Sportdiving). It is difficult to say how many have searched for this elusive grey wolf, for most efforts to find her have been undertaken quietly. I was aboard the dive boat Seeker in 1994 and 1995, when we dived Pan Pennsylvania and searched unsuccessfully for U-550. Since the turn of the millennium there have been several other acknowledged searches for the submarine. The publisher of this magazine, Joe Porter, along with Richie Kohler and Evan Kovacs, conducted a number of searches, while a second group, led by Mark Munro, also looked for the wreck in the same time period. | |

|

Joe Mazraani began diving in 1997, and quickly took to shipwreck exploration. His interest in U-550 began in 2000, learning her story from Axel Niestle's chronicle of U-boat losses during the Second World War. He yearned to discover a new shipwreck, and was particularly interested in the two diveable U-boats whose location remained a mystery (U-215 had not been located at that time). He was interested in a number of salvage projects as well, and ultimately decided he needed a boat to pull off the complicated undertakings he had in mind. In the winter of 2010 he bought a 45-foot Novi lobster boat and named it Tenacious. After outfitting it and breaking it in for wreck diving, he and a team of friends set out to recover the remaining helm wheel from the stern of the Ayuruoca, sunk in the Mudhole off the northern New Jersey coast (the first of the pair of big wooden wheels had been brought up in 1993 by the crew of Seeker). After 26 working trips, the prize was finally recovered in November 2010 and put on display the following spring at the dive show Beneath the Sea. With project number 1 successfully completed, it was time to turn his attention to U-550, but finding the submarine would prove more difficult in 2011-2012 than it had in 1944. | |

|

Finding a sunken submarine in 300+ feet of water would require a better tool than an ordinary depth sounder, and the obvious choice was side scan sonar. Able to cover large swaths of ocean bottom by towing an electronic "fish" in a "mow the lawn" pattern, side scans are both expensive and require experience to operate and, most importantly, interpret the data. Mazraani decided to hire an expert for the effort, Garry Kozak, and the first field search was conducted in July 2011. Leaving Montauk, NY aboard Tenacious were John Butler, Steve Gatto, Joe Mazraani, John Moyer, Harold Moyers, Tom Packer and Garry Kozak. For two days they towed the fish through a predetermined search grid with the belief that finding her was simply a matter of time. Despite covering 40 square miles of ocean bottom, however, the team returned to port empty handed�but they had learned where the submarine wasn't. | |

|

Un-deterred and undiscouraged, the group buckled down and really "hit the books," making multiple visits to the National Archives to acquire as much information, from as many original sources, as possible. It soon became obvious that positions and events reported in official documents were literally all over the map. Theories about what had actually happened sixty-odd years ago, and where, were developed, rejected, modified and re-examined. Eventually, a plausible theory and search grid was developed for a second effort. In July 2012 all that research would be put to the test when another search trip left Montauk, NY aboard Tenacious. Aboard this time were Steve Gatto, Joe Mazraani, Tom Packer, Brad Sheard, Eric Takakjian, Anthony Tedeschi and of course, Garry Kozak. | |

|  |  |

| Searching for U-550 | ||

|

Arriving on-site at 6:30 am, we deployed the sonar fish on a long cable and began "mowing the lawn." Plowing slowly and methodically through the ocean at 4-5 knots, the boat followed invisible electronic lines drawn across the ocean's surface by modern navigation tools. At first, we all watched the sonar screen waiting for something to appear, but as hour after hour passed it was clear this would be a long effort. We read, talked, ate, drank coffee and re-examined our research material; when we were done, we started the cycle over. We had plotted dozens of fisherman's "hang numbers" on our charts, and as we approached each mark everyone clustered around Garry and his magic computer monitor in anxious anticipation. While we found a number of sonar "anomalies," as Garry called them, none quite looked like a submarine. We noted their position for closer examination later and drove on. | |

|

On the trip out from Montauk, an easterly wind had forced us to pound straight into the seas for 12 hours, but the ocean had since lain down, and we now moved gently across a liquid mirror of water. We were acutely aware that this marvelous calm was predicted to end after two days, however, and what was to follow would not be pleasant. Toward dusk we decided to modify the original plan and search through the night, taking shifts sleeping, driving and watching the sonar display. By mid-morning of the second day, we had exhausted our entire main search grid without finding any likely looking targets. While panic would be too strong a word, the situation was becoming worrisome, and we began searching two secondary areas we had marked on our chart. | |

Toward dusk of the second day, as we completed scouring the auxiliary areas, things were getting pretty grim on board Tenacious. We had covered our carefully planned search zones and, while we had found targets, none "looked" much like a submarine. Up to that point Garry had been using a very low frequency sonar fish for the broad area scans, and although it gives a low-resolution image, it covers a very large area. We now hauled in the cable and deployed a second, higher frequency instrument that would give us a better look at some of the targets we had found. | |

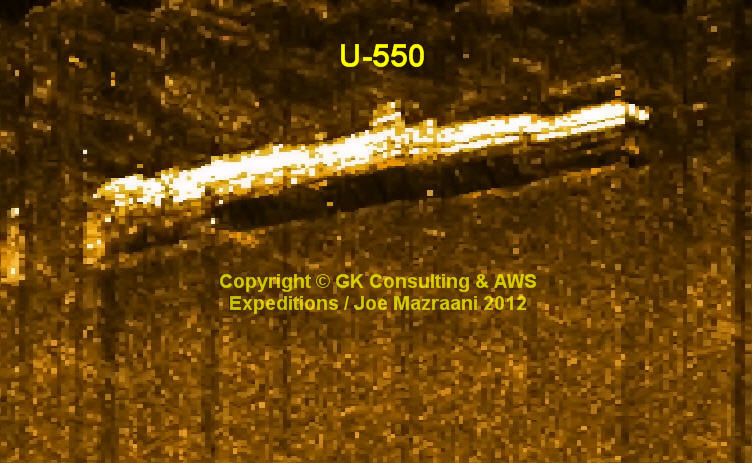

At this point Lady Luck made an appearance to give us an assist. Approaching one of the previously located targets, we actually picked up a small spike on Tenacious' depth sounder before the long, cigar-shaped image of a sunken submarine appeared on the side scan monitor. As we stared anxiously at Garry, then in near disbelief at the monitor, then back again at Garry, his demeanor slowly changed and a broad grin spread across his face. "This is looking good," he said through his smile. After making several more passes with the higher frequency fish, Garry was nearly certain we had found the lost U-boat. | |

|  |

| Gary Kozak's face lights up as he realizes we have finally found our target (left); sonar image of U-550 (right) | |

Our spirits soared as we began to realize that we had actually done it�we had found U-550. Wanting proof positive, we decided to try out a lighted video drop camera that Steve Gatto had recently acquired. Dangling a high-tech yo-yo on a 100-meter long cable, we spent the better part of an hour carefully maneuvering the boat to get the camera over the target. For a few precious seconds the camera bounced over the wreck, surrounded by swarms of pollock and krill attracted to the lights, and we watched in exhilaration as the camera passed over a tightly closed torpedo-loading hatch. U-550 had been found! | |

Although we had brought dive gear with us, like the now-standard documentary formula, imminent bad weather chased us from the wreck site shortly after confirming the target was a submarine. Pounding through yet another rough sea back to Montauk, we immediately began planning a return trip to touch and explore what we had just discovered. Six days later a weather window floated gently across the ocean, and we returned to the scene of a battle we had now become intimately familiar with. | |

Descending through a clear but increasingly dark water column, we land on the decks of history 100 meters beneath the sea. The scene lain out before us is both stunning and frightening: U-550 sits upright, listing slightly to port, cloaked in the darkness of the stygian depths. Her decks are in a remarkable state of preservation�we all agree later that she is one of the most intact submarine wrecks we have ever seen. The depth is extreme, however, and I find it difficult to shake the feeling that we are on the edge, perhaps beyond the edge, of safety, and a long, long way from home. | ||

|  |  |

| Steve Gatto lights up U-550's conning tower in an eerie scene 100 meters down (left); Steve Gatto swims over remarkably intact decking (center); close-up of the submarine's conning tower and RDF aerial (right) | ||

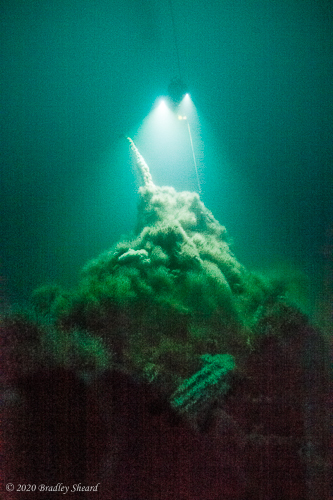

The signature feature of a submarine is surely its conning tower�a lonely sentinel rising above a nearly featureless steel tube. In the case of U-550, that protuberance has the appearance of a bushy, soft-edged hillock standing proud over her flat, listing deck. Well camouflaged by thick hydroids and a thin veil of fishing net, its smooth, amorphous shape is broken by two unmistakable features. Marking the forward end is the distinctive, ring-like RDF antenna�a circular icon asserting its human origin amid the living camouflage of the depths. Not far behind is the tall, lance-like attack periscope stabbing into the darkness, still in its fully extended position�an echo through history from the short, violent battle that placed her here. | ||

Swimming forward over the submarine's deck we first pass the galley hatch, still submerged beneath a network of steel framing�the hatch is eerily open to the sea. It is striking how well preserved her decks are, with steel gratings still in place after 68 years immersed in corrosive brine. Toward the bow we stop at the forward torpedo-loading hatch, sprung open on its hinges. There is a large and mysterious crack in the pressure hull emanating from the circular opening. Was this damage caused by Joyce's depth charge attack? It seems far too large for the boat to have reached the surface again, but what else could have caused it? A nearly irresistible siren call to enter beckons, but the dark, cavernous interior swallows the beam of a dive light while revealing little of what lies inside. Perhaps on another dive�. | ||

Seven divers swam over the decks and around the hull of the U-boat for two days, awestruck by a long awaited rendezvous with history. Only reluctantly did we leave the wreck at the end of our necessarily short dives. With dive support provided by Paul McNair, Steve Gatto, Joe Mazraani, Tom Packer and Brad Sheard dived this historic wreck with open circuit gear, while Mark Nix, Pat Rooney and Anthony Tedeschi used closed-circuit rebreathers. The dive proved an exciting and emotionally fulfilling achievement after a long search conducted through history as well as beneath the sea. | ||

Following our discovery and two dives on U-550, we put out a press release to announce the find to the world. Intermingled with congratulatory messages and inquiries by both divers and historians, a truly unexpected epilogue began to unfold. Interest in the discovery seemed to spread like wildfire across news outlets and the Internet, and the story began to catch the interest of both survivors and the families of those involved in a nearly forgotten battle that most could only know from the pages of history. Voices from both sides of the battle reached out and spoke to us, congratulated us, often sending news clippings and contemporary photographs from their personal collections. The interest, excitement and enthusiasm were overwhelming, and we decided to send a small booklet of underwater photographs of the wreck to all who contacted us. It was a small gesture, but allowed us to share our discovery with those whose involvement in U-550's story was far more intimate than our own. | ||

|

| The team presents Morton Raphelson, Pan Pennsylvania's radio operator, with a shadowbox containing a plate recovered from the wreck of his ship |

All images, text and content Copyright © Bradley Sheard. All rights reserved.