|

Then-and-Now

A Photographer's Journey through Time and Technology

| This article was originally published in issue 35 (2015) of Wreck Diving Magazine. |

|

Standing on the ocean floor 230 feet down, my heart pounds with excitement as I stare directly into the passenger steamer Carolina's huge propeller. Gazing up at what remains of her stern, my mind drifts backward in time�not to the beginning of the last century, when the ship was torpedoed by a marauding German U-boat, but to the year 1995, when the wreck was first discovered. It was 18 years ago that I stood in this exact spot, pointing a camera at this same scene�but how different it appeared now! Gone were the elegant ribs that once gave shape to the ship's rounded fantail. The circular band of steel that wrapped around her curved transom, proudly displaying the well-camouflaged brass letters that identified the wreck, lies twisted and tattered on the ocean floor, barely recognizable for what it once was. Back then I was diving open circuit trimix and carrying a housed 35mm camera loaded with black & white film, push-processed to overcome the lack of ambient light. The resulting image is hauntingly dark, with blocked up shadows and golf ball sized grain�an atmosphere photo for sure. Today I'm using a closed-circuit rebreather and carrying the latest generation digital camera, capable of capturing images that seem light years ahead of that grainy one from two decades ago. But the picture in my head, and in my old photograph, has evaporated into history, never to be recreated, for the wreck is no longer what it once was. While the passage of time has brought me fantastic new technological tools for capturing images, those same years have led to the collapse and deterioration of the very subjects I seek to photograph. | |

| * * * | |

| |

|

Stored on shelves in a small basement workroom are most of the underwater cameras I have owned�a small collection of the dynamic history of underwater photography over the past 30 years. Several Nikonos cameras (still alive after multiple flood-and-repair cycles) and a badly chipped 15mm lens represent my first tools of the trade. My first housed camera was a big white, nearly bulletproof Aquatica beast for the Canon F-1n 35mm SLR. Purchased in 1989 after one-too-many Nikonos floods (OK, I was taking them deeper than they were rated to go�OK, much deeper!), the new housing was only "certified" to 250 feet�but a National Geographic photographer had taken one to 700 feet mounted on a submarine, and it had worked fine�I was sold! There was no Internet then, and purchasing it required a one-on-one, sit-down meeting at Adorama in New York to order the device, but it was soon mine. After years of reliable service from my Canon, the age of autofocus dawned and I purchased a pair of Nikon N90s cameras and matching Aquatica housings. A much smaller and lighter alternative to the big Canon, I discovered I could carry two of the Nikons at the same time, doubling the 36 exposures a roll of film would give me, as well as having a choice of lenses during a dive. | |

| * * * | |

|

Over the years I have watched with dismay as the wrecks I have come to love have slowly, inexorably, collapsed and deteriorated. With wrecks I visited often, the changes were masked by familiarity�much like the growing child you see everyday, the continuous accumulation of alterations goes nearly unnoticed. The metamorphosis was far more evident when calling on shipwrecks I had not seen in many years, however. Returning to the USS San Diego in July 2004, a site I had "grown up" diving on and in, was astounding. Once upon a time I knew my way around the inside of her inverted hulk better than my own living room (or so it seemed). Seeing her for the first time in a decade, it was quickly apparent that venturing inside would quickly get me lost�she had become an entirely different world. Her hull had buckled and collapsed downward as if stomped-on by Godzilla, crushing the life from her body and making the interior an unfamiliar maze of mangled steel and debris. Better to remember her as she once was��I have not been back since. | |

| * * * | |

|

Since my earliest forays into underwater photography, I have been more interested in capturing images of the "big picture" view of sunken ships, rather than their small details. Physics necessitates that such images rely on ambient light rather than strobes or video lights, yet that naturally occurring light is in short supply in the abyss. My earliest attempts relied on Kodak Ektachrome 400 slide film, push processed to ISO 800�a very fast film at the time. Later, I discovered that high-speed black and white films, such as Kodak's TMAX 3200, gave me superior results�and there was contrast in the images! The downside was film grain�akin to noise in today's cameras. The grain seemed monstrous, especially when the film was push-processed to gain speed. Obsessed with limiting the grain in ambient light images, I spent nearly two years designing and building a housing for a medium format film camera�the Mamiya 645. The result was a 30-pound aluminum and Plexiglas monster that served its purpose, but proved to have as many drawbacks as advantages. | |

| * * * | |

|

The Andrea Doria may represent the ultimate timeline in the deterioration of a shipwreck. She was sunk only two years before I was born, and Peter Gimbal made his infamous first dives to the iconic shipwreck only hours after she made her journey to the bottom. My own first experience with the Doria didn't come until 1984�by then she had endured 28 years in the depths�but what a magnificent sight she was! Accustomed to shipwrecks that were broken and twisted piles of steel, here was a nearly unspoiled ship lying on its side. Navigation, at least externally, seemed as simple as walking her decks before she sank. Sure, visibility was often murky and dark, currents were often strong and unpredictable, but she looked like what a layperson imagines a shipwreck to be. Nothing remains the same for long, however, and as the years passed her interior continued to disintegrate and her hull plating began to sag. Once again it was a long absence from the wreck that smashed the memories I had of diving her. Returning in 2006 on the 50th anniversary of the collision that sent her to the bottom, I was greeted by rolling waves of warped and misshapen steel plating, punctuated occasionally by recognizable features entirely out of place: the mighty Everest of wreck diving had fallen. | |

| * * * | |

|

When digital photography came of age, a new series of housings and cameras was required to keep up with rapidly evolving technology. My first foray into the new world of digital imaging was a Nikon D70s paired with an Aquatica housing�an experiment really�to see what the new medium could do. This was followed by a succession of finely engineered Seacam housings for the Canon 5D (the first affordable full-frame digital camera) and then the 5D Mark II. This was followed by the incredible Canon 5D Mark III housed in a nicely built Aquatica, and finally a Canon 5DIV in a Nauticam housing--a thing of beauty. Each new camera system, in its time, provided a leap forward in capability, were it increased reliability at depth, smaller packaging, autofocus or better image quality. It must be difficult for photographers who started after the digital revolution to understand how incredible their current tools are. Trying to make images in the dimly lit depths (without artificial light) was a supreme challenge when film was the only medium available; today's digital cameras are so sensitive to low light that the constraints of film seem archaic (it was not so long ago an ISO rating of 400 was considered fast!). There was a certain magic involved in the darkroom of yesteryear, however, that many of today's photographers will never enjoy. Watching an image slowly appear on a piece of sensitized paper immersed in a chemical bath was a nearly mystical experience that I sometimes miss . . . | |

|

The incessant march of technology is constantly providing the photographer with new and better tools to make images of the world; for me, that world is the myriad of deteriorating shipwrecks lying in our oceans. I often gaze at some of my favorite images from years past, and long to return and re-photograph the scene with a modern digital camera. Unfortunately, those scenes no longer exist. While the ships are still there, the relentless passage of time has taken its toll on each of them. The wrecks continue to crumble and collapse, and neither God nor man (nor NOAA!) can stop the inevitable process of decay that represents the necessary and natural order of things. All will eventually enter the final stage of their journey into oblivion, just as the Anglican burial service foretells: "earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust," and there is no reprieve from that fate. | |

|

Each of the images I dream of re-shooting represents an instant in time that cannot be revisited and cannot be recreated�all I can do is make new images of the way these wrecks exist now, in a more advanced stage of decay. While this harsh reality may disappoint the photographer, the circumstances do present another possibility. By drawing on my collection of older images, and combining them with contemporary photographs of the same scene, I can offer a poignant study of the contrasts between collapsing shipwrecks and the technological evolution of photography. The original images of more pristine wreck sites, taken with traditional equipment and film, are diametrical opposites to the photographs made with modern digital tools, but of significantly deteriorated shipwrecks. The pairing represents a kind of Yin and Yang of photography and sunken ships�a contrast between old and less spoiled, and new and decomposed, each existing in its own time. Presented here is a small sampling of these contrasting scenes�matched sets of photographs taken nearly two decades apart with vastly different camera systems. It is my hope to continue this project as the wrecks continue to collapse, while time and technology marches ever forward. | |

|  |

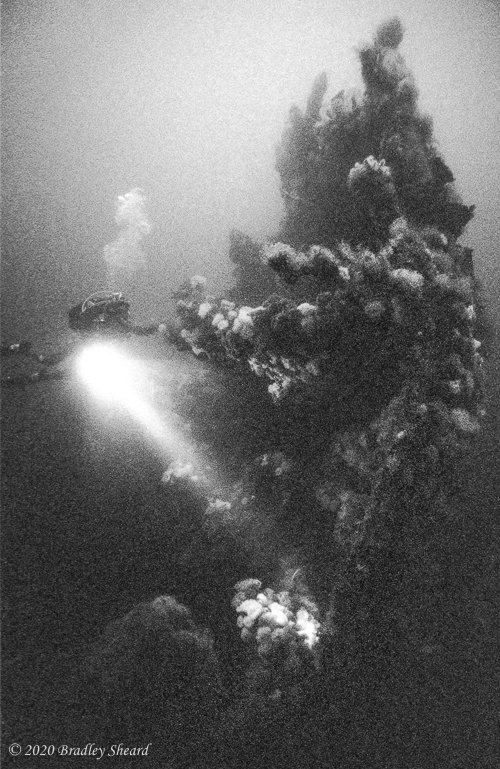

| June 1996: Canon F-1n and 14mm lens in Aquatica housing, T-Max 3200 film push processed to ISO 12,800 | October 2013: Canon 5D Mark III and 14mm lens in Aquatica housing, shot at ISO 6400 |

|

In 1996, the year after we first discovered her, I swam to the stern of the passenger liner Carolina with Tom Suroweic. I wanted to try and capture a "big picture" shot of the stern of the wreck, for at the time the form of the ship's fantail was still framed out by delicately curved ribs. It was here that John Chatterton had uncovered the well-camouflaged brass letters spelling out her name and homeport of New York, positively identifying the wreck on June 15 1995, when we first dived her from Paul Raguso's Bounty Hunter. The Carolina had been sought by wreck divers for many years, and we were lucky enough to have picked the right set of "hang numbers" to dive that year. | |

|

In 2013 I returned to the stern, this time armed with the latest generation digital camera. While the modern camera captures far more detail of the underwater scene (above right), particularly in the shadows, the wreck itself had collapsed significantly during the 17-year interval. The ribs defining the fantail have disappeared completely, leaving the bottom of the hull, rudder and propeller as the most recognizable features of her once magnificent stern. | |

|  |

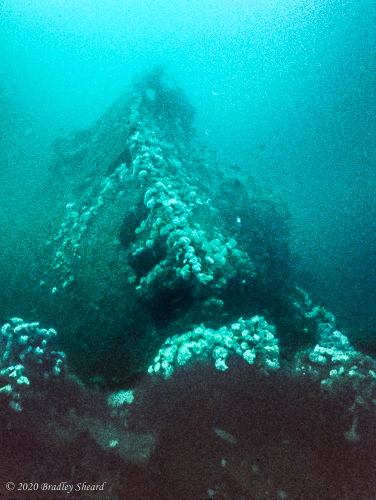

| July 1993: Nikonos II camera and 15mm lens, T-Max 400 film push processed to ISO 800 | June 2011: Canon 5D Mark II and 15mm lens in Seacam housing, shot at ISO 400 |

|

I first had the privilege of visiting the stern of the Tamaulipas (also known as the "Far East Tanker") in 1993. The torpedoed tanker lies both far south of Cape Hatteras and far east of Cape Lookout, and is not visited often. We glided 40+ miles across a glassy sea, punctuated by flying fish and Sargassum weed�rare conditions for Cape Hatteras. When we arrived we found a magical wreck featuring the intact skeletal remains of the Tamaulipas' after tank sections (above left). Shooting with black & white film and a Nikonos II, I managed to capture a small part of the scene for posterity, but always longed to return to the wreck. | |

|

While the visibility seems to be hit or miss on this wreck, the marine life is nearly always spectacular, and when I returned in 2011 armed with a housed digital SLR, the fish were so thick and wild that it reminded me of a marine-life-rodeo. Jacks buzzed and swooped through schools of baitfish like high-speed fighter jets on the hunt, while sand tiger sharks filled every nook and cranny of the ship's collapsing tank sections. The wreck had settled somewhat over the past two decades, but still appeared largely as I remembered her; sadly, the following winter the wreck collapsed noticeably downward, and the deterioration is likely to accelerate as she continues her inevitable journey to rubble. | |

|  |

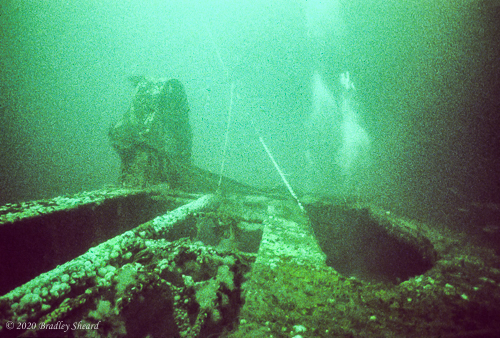

| August 1987: Nikonos IV and 15mm lens, Kodak Ektrachrome 400 film pushed processed to ISO 800 | August 2013: Canon 5D Mark III and 14mm lens in Aquatica housing, shot at ISO 3200 |

|

Many years ago I made my very first "deep" dive to a cod-fishing wreck known by the popular name "Virginia," actually believed to be the World War I U-boat victim Sommerstad. The wreck lay in 170 feet of water 35 miles south of the Long Island coastline; that the wreck was a popular fishing spot was clear, for she seemed to be wrapped in a cocoon of heavy monofilament. The site was blessed with fabulous visibility, making her an alluring destination for Northeast wreck divers. Wearing twin 80's and carrying a Nikonos camera with high-speed Ektachrome slide film in some of my earliest days of underwater photography, I was spellbound by the ships bow, of which I managed some drab and muddy ambient light images. Her prow was intact and tipped backward so far that her stem aimed nearly skywards, mimicking contemporary reports of her attitude while sinking. | |

|

It would be 26 years before I returned to the wreck again, now with a closed circuit rebreather and digital camera. While still easily recognizable, her bow is halfway to collapse. The years have caused the magnificent bow I remembered to settle into a nearly vertical orientation, while her deck has slid free from the hull and collapsed to the bottom, exposing the poor ship's innards for all to see. The forward hull plates have splayed outward like a collapsed tepee, taking on a gentle undulating curvature, while the now exposed, twin hawse pipes drip anchor chain from their gaping maws. The ship's stem is still intact, punctuated on either side by the same pair of big navy anchors I had seen years earlier, when they stood so high above the ocean bottom. | |

|  |

| June 1992: Nikonos camera and 15mm lens, T-Max 400 film push processed to ISO 800 | July 2009: Canon 5D Mark II and 15mm lens in Seacam housing, shot at ISO 2000 |

|

The waters off Cape Hatteras make for wonderful diving�when you can get offshore, that is. There was a reason Orville and Wilbur Wright first flew their airplane over Carolina's Outer Banks--Wind. Combining frisky winds with two intersecting oceanic currents makes it a challenge to visit wrecks like the World War II freighter Malchace. Diving her two decades ago was a rare treat I enjoyed on only a few occasions. I remember marveling at the growth on the bottom of her inverted hull�a veritable cornucopia of coral and color, regularly punctuated by odd whip corals that looked like living corkscrews. Dealing with the strong current and 200-foot depth, while breathing air, made it difficult to see more than a snapshot of the wreck's entirety, however. Her two big boilers amidships were a landmark I had seen on several occasions. | |

|

Seventeen years later I was thrilled to circumnavigate the entire wreck in a single dive, and this time the experience was enhanced by the clarity brought about by a bit of helium. It was a perfect day: a glassy sea with almost no current and 80-100 feet of visibility. I glided in slow motion over and around the wreck I had seen in only bits and pieces previously, feeling at peace and in perfect harmony with the sea, the marine life and the wreck. It was almost shocking how small the wreck seemed now, as I was easily able to swim from amidships to stern to bow and back again�finally able to see the forest for the trees. Those same two boilers lay just as they had years earlier, although the hull plates surrounding them had collapsed a bit more than I remembered�or perhaps it was just the helium I was breathing . . . | |

|  |

| July 1989: stern bridge wing, Nikonos camera and 15mm lens, Kodak Ektachrome 400 push processed to ISO 1600 | July 25 2006: somewhere near stern, Canon 5D and 14mm lens in Seacam housing, shot at ISO 3200 |

|

Once upon a time, the Andrea Doria was considered by many to be the "Mount Everest" of wreck diving. Far offshore and difficult to reach, prone to strong currents and poor visibility, the Italian liner lay on her starboard side in waters deep enough to be considered extreme at the time. She had a certain magic about her, however, that drew divers to return to her year after year. Part of that allure was surely the well-preserved condition of the wreck, for here was a huge sunken ship that still looked like a ship. The extreme conditions always made photographing her a challenge, especially any attempt to capture the "big picture" majesty of the immense liner. I often tried using fast slide film and push-processing to deal with the dim, dark conditions, but the results were mostly disappointing. | |

|

In 2006 I managed to squeeze in a single dive to the Doria, my first in 11 years, on the 50th anniversary of the collision that sent her to the bottom. The dive brought mostly disappointment, however: serious collapse had overtaken the once proud liner, the visibility was poor (that much was familiar!), and the wreck's deterioration made it difficult to figure out exactly where we were tied in. For me, the Doria's "magic" was gone�what was once a majestic and largely intact liner had crumbled into a difficult to navigate mountain of rubble. The Promenade Deck, once the hallmark of the Doria's upper (port) side, now sags downward, its steel plating bent into folds like a set of droopy curtains. Interior stairways lie at haphazard angles outside the wreck, atop piles of non-descript steel plating, all seemingly held together by a plethora of fishing nets. | |

|  |

| June 1991: Canon F-1n and 17mm lens in Aquatica housing, T-Max 3200 film push processed to ISO 6400 (engine in foreground to right) | August 2009: Canon 5D Mark II and 14mm lens in Seacam housing, shot at ISO 3200 |

|

My first dive to the wreck of the Victory ship Ocean Venture was off Mike Boring's boat Sea Hunter out of Virginia Beach in 1991. The waters off the coast of Virginia were new to me, but the boat was an old friend, as I had "grown up" on her when she called Freeport NY home and I was new to wreck diving. Another victim of the ravages of World War II, Ocean Venture soon became one of my favorite "southern" wrecks. Her bow sat bolt upright, while the stern listed to port, but my favorite part was always "the Cathedral." Located adjacent to the big triple-expansion steam engine, and partly surrounding it, swimming inside the anemone-covered vertical framework of a nearly intact coalbunker was a reverential experience. Trying to capture that feeling on film was difficult, for the limitations of light and film added to the challenge of trying to capture an ethereal moment in time with a two-dimensional medium. | |

|

It was nearly twenty years later that I saw her again. "The Cathedral" was still there, but was a mere shadow of its former self, having shrunk in size as the columns and deck plates fell to the ocean floor one by one over the years. The great steam engine, once partly hidden from view by the surrounding curtain of vertical beams, now stood high above the remainder of the wreck, fully exposed on all sides. Sadly, the following winter completed the destruction of the monolithic Cathedral�dives the following summer revealed that this oceanic Stonehenge had collapsed completely, never to be seen again. | |

|  |

| June 1992: Canon F-1n and 17mm lens in Aquatica housing, Kodachrome 64 film | September 2013: Canon 5D Mark III and 14mm lens in Aquatica housing, shot at ISO 800 |

|

The passenger steamer Proteus is surely one of Cape Hatteras' iconic shipwrecks. Lying at moderate depth and generally blessed with fabulous visibility in summer months, visiting divers "back in the day" often had visions of beautiful brass windows, well camouflaged by hard coral growth, dancing in their heads as they swam over her remains. The ship's beautiful rounded fantail lists hard over to port, yet rises high enough off the sandy ocean bottom to allow resident sand tiger sharks to circle continuously beneath it in an endless marine-life carousel. The shark's circular cleaning station took them in a grand orbit that passed beneath the stern, past both the rudder and big propeller and then out over the sand and back again. | |

|

As years passed an observant diver could see that the Proteus' impressive stern was slowly corroding and rotting, bit-by-bit succumbing to the caustic oceanic brew. Eventually, the steel hull had to give way, and sometime in the past decade that once-imposing fantail broke free and fell to the ocean floor. The ever-present sand tigers were forced to alter their racetrack course just a bit, but can still be found there, circling in that endless procession that will likely continue well beyond our time on this earth. | |

|  |

| July 1991: Nikonos camera and 15mm lens, T-Max 400 film | June 2014: Canon 5D Mark III with 15 mm lens in Aquatica housing, shot at ISO 800 |

|

My first exposure to wreck diving out of Cape Hatteras was in the early 1990s on Captain Art Kirchner's Margie II. Artie was always up for trying new wrecks when conditions allowed; when they didn't, we usually managed to make it to one of the "old standbys," one of which was the World War II tanker Lancing. The wreck is big and quite intact, lying upside down in 170 feet of water near Diamond Shoals, making the site subject to current and the visibility quite variable. When conditions were good, however, it was a spectacular dive. It was hard not to be impressed by the scene at the wreck's stern: a huge keel, massive propeller and a giant rudder, centered amidships, rising high above the bottom�exactly the kind of image conjured up by the word "shipwreck." | |

|

Twenty-three years later, the scene appears the same at first glance. Closer examination, however, shows that the rudder has separated completely from the keel: all the pintles and gudgeons have let go, and only the rudder shaft still holds the massive slab of steel in place. The rudder is now turned to starboard, having moved from its original centered position. There are other subtle changes in the wreck as well if you look closely, such as badly deteriorated railings on the underside of the stern, which twenty-years ago were nearly perfect. | |

|  |

| August 1994: Nikonos camera and 15mm lens, T-Max 400 film push processed to ISO 800 | July 2011: Canon 5D Mark II and 15mm lens in Seacam housing, shot at ISO 200 |

|

There are, of course, wrecks and structures that seem to defy the laws of collapse and decay, or at least follow them on a different time scale. In the early 1990s I longed to visit some of the less commonly dived World War II wrecks out of Morehead City in North Carolina. Unfortunately, as happens on the Carolina Banks, wind and weather seemed to conspire against me. Then one not-so-calm-day in August 1994, Brian Skerry and I managed to overcome multiple obstacles and make the long ride out to the sunken tanker Naeco. The wreck seemed to sit on an unfamiliar hardpan bottom, and much of it was flattened. At the stern, however, there was a magnificent steering quadrant still standing proud of the bottom on its rudder shaft, and Brian and I did our best to capture the moment on film. | |

|

Returning to the wreck seventeen years later on a beautifully calm ocean, the wreck appeared much as I remembered it, including the steering quadrant at the stern, which still stood upright. | |

|  |

| May 1992: intact deck railing, Canon F-1n and 17mm lens in Aquatica housing, Kodachrome 64 film | August 2011: intact deck railing, Canon 5D Mark II and 14mm lens in Seacam housing, shot at ISO 5000 |

|

The steamship Ayuruoca, more commonly known as the "Oil Wreck," lies in a silty undersea trench south of New York Harbor that represents the ice-age remnant of the ancient Hudson River valley. Locally called "the Mudhole," this submerged gulley has been the holding tank for river effluent flowing out of the Hudson for millennia, making the ocean depths here dark and foreboding. Diving here is challenging, and photography even more so, for the suspended silt seems to suck-up light like a vacuum, and visibility rarely exceeds 10-15 feet. The narrow ribbon of deeper water does provide some protection to the wrecks that lie in its grasp however, apparently sheltering them from the destructive effects of wave action during storms. The Ayuruoca sits upright and intact on the bottom, although she is cut neatly in two just behind the bridge as a result of the collision that sank her. | |

|

I have dragged a camera along during dives to the wrecks in the "Mudhole" on many occasions, but the results are mostly disappointing. The lack of ambient light necessitates the use of strobes, and the suspended particulate matter nearly guarantees the underwater photographer's nemesis�backscatter. The incredible light sensitivity of digital cameras, however, combined with a rare day of (relatively) good visibility, sometimes allows the capture of an image with only ambient light, largely eliminating the dreaded backscatter caused by strobes. | |

|  |

| June 1992: Canon F-1n camera and 17mm lens, Kodachrome 200 film at ISO 200 | August 2014: stern, August 2014, Canon 5D Mark III and 15mm lens in Aquatica housing, shot at ISO 800 |

|

The freighter Manuela, southeast of Hatteras Inlet, is surely one of the prettiest wrecks in North Carolina waters. Lying far enough offshore to almost guarantee blue water and great visibility, yet not so far that the current is insurmountable, the Manuela has long been a Hatteras benchmark. Her hull is intact but broken�a dichotomy that may seem strange until you have seen her firsthand. Her inverted midship hull has a twist�there is a massive debris field formed by her innards spilled-out across the ocean bottom. The bow lies on its starboard side at one end of the wreck, while the stern, still intact two decades ago, lay on its side at the opposite end. | |

|

Twenty-two years later the midships section of the wreck appears largely the same, but the bow is nearly a skeleton with much of its hull plating gone. The ship's stern has nearly completely collapsed, however, and is only a remnant of what it once was. | |

All images, text and content Copyright © Bradley Sheard. All rights reserved.