World War II U-boats

| U-85 (sunk April 14, 1942) | |

|

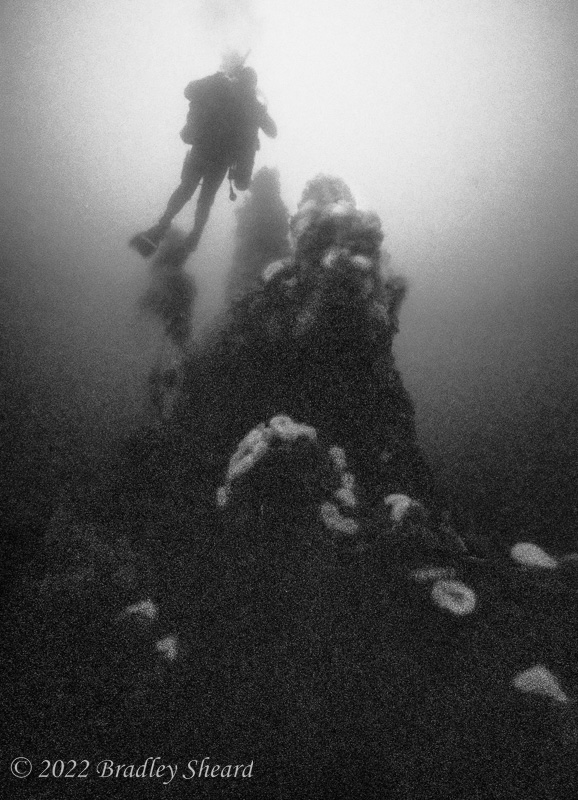

The German type VIIB submarine U-85 left St. Nazaire France in late February 1942 for what had become known as the "Happy Hunting Grounds" to German submariners--the United States Eastern Seaboard. Four months after the US had entered the war, the U-boats had sunk 71 ships in the Eastern Sea Frontier without the loss of a single U-boat. That luck was about to end, however, as US forces gradually adjusted to a wartime footing. The four-stack destroyer USS Roper was zig-zagging off the North Carolina coast on the night of April 13-14. The moonless night sky was dark and clear, with stars shining brightly, casting their dim light upon a calm sea that shone with the phosphorescent glow of bioluminescent plankton. Making 18 knots Roper was equipped with both radar and sound search equipment. Just past midnight the radar operator reported a contact at 2700 yards; the sound operator quickly picked up high-speed screws along the same bearing. As Roper closed the distance to the target, lookouts spotted the wake of a small vessel and increased speed to 20 knots as the target began to take evasive action. The destroyer closed to within 700 yards; a torpedo streaked down the Roper's port side. The destroyer's crew trained a searchlight out into the darkness, illuminating the conning tower of a submarine. Caught on the surface in shallow water, U-85 was unable to dive and tried to run. Men poured out of the U-boat's conning tower as Roper's crew opened fire. Machine guns cut down some of the men, while the 3” gun scored a hit at the base of the conning tower. The submarine began to settle by the stern as the crew abandoned her. Roper charged ahead directly over the sinking submarine, launching a pattern of 11 depth charges into the shallow water, pounding both the submarine and its now swimming survivors. At dawn oil slicks and floating debris were sighted. Spotting bodies in the water the destroyer lowered boats to begin the arduous task of recovering 29 bodies from the sea. Today U-85 has become a popular dive site for recreational divers. Resting in 90-feet off water east of Oregon Inlet, North Carolina, the wreck lists to starboard. Lying North of Cape Hatteras, the remains sit in cold, green water and visibility varies greatly. |

|

| U-85's conning tower hatch (August 1994, film) | |

| U-352 (sunk May 9, 1942) | |

|

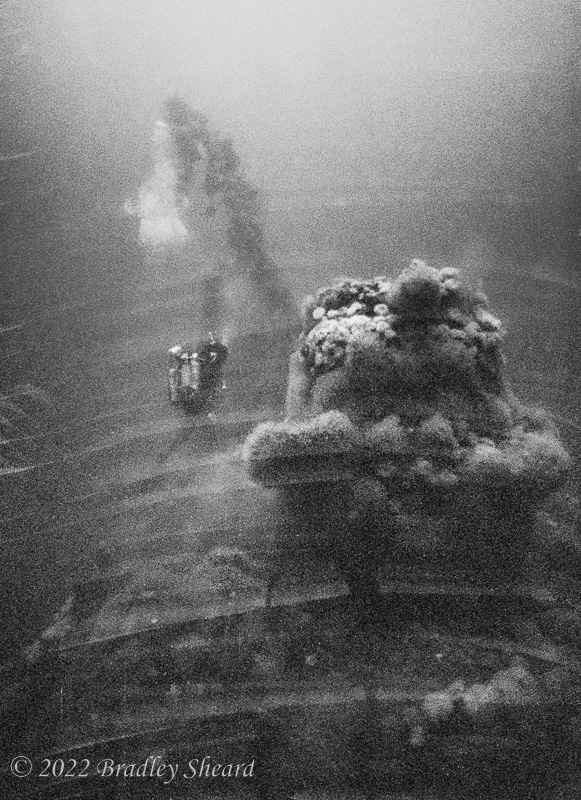

German submarines found good hunting off the American coast in the first half of 1942, but not all were lucky enough to take advantage of the easy targets they were offered. Hellmut Rathke's U-352 was unable to sink a single ship during her two war patrols, and earned the dubious distinction of being the second U-boat sunk off the American coast during the war. The US Coast Guard cutter Icarus was cruising south of Cape Lookout, North Carolina, at a comfortable 14 knots late on the afternoon of May 9. At 4:20 the sound operator picked up a "mushy echo" 100 yards ahead on the port bow. As the cutter closed the distance the contact grew stronger and more distinct, and five minutes after the initial sound alert a violent torpedo explosion 200 yards off the port quarter got the full attention of the ship's commanding officer, Lieutenant Maurice Jester. Jester immediately sounded General Quarters and brought the Icarus hard about. Propeller noises were heard on the sound gear and Icarus bore down on its target, which now appeared directly below where the torpedo had exploded. The destroyer dropped a pattern of five depth charges, came about again and dropped three more charges, this time bringing large air bubbles to the surface. Icarus followed up those attacks with two more passes, dropping a single depth charge each time. Aboard U-352, Hellmut Rathke had attempted a submerged daylight attack in shallow water and was now paying the price; he would later tell interrogators "Thirty meters of water...what could I do?" Icarus' first set of well-aimed charges destroyed the periscope and killed the officer in the conning tower. "Gauges and glasses were smashed in the control room. The deck was littered with broken gear. Lockers burst open. Crockery and other loose objects were flung about the boat." Convinced the submarine was lost, Rathke brought his boat up and ordered the crew to abandon ship. As the U-boat broke the surface, down by the stern, Icarus opened fire with machine guns and her three-inch deck gun, dissuading the German's from manning their own gun. Once they found the range, Icarus' gun crew scored repeatedly on the submarine's hull and conning tower, while a hail of machine gun bullets descended upon the men pouring from the conning tower. Five minutes after surfacing the U-boat sank, taking thirteen men with her to the bottom, and leaving behind 33 German sailors swimming in the sea. Meanwhile Icarus, not yet convinced the submarine was finished, circled around and dropped one last depth charge over the spot where the U-boat had gone down. Unsure whether or not to pick up the survivors, Lieutenant Jester radioed headquarters asking for instructions. Thirty-odd minutes after the submarine sank, Icarus finally began to pick up the German survivors, transporting them to the Charleston Navy base and turning them over to Naval Intelligence, who would learn little of value from the well disciplined crew. The U-boat's survivors became prisoners of war, and were interred for the duration of the conflict. Today U-352 is one of the most popular dive site off the North Carolina coast. Resting in 115-feet of often clear Gulfstream water south of Morehead City, North Carolina, the wreck sits on a sandy bottom. Divers travel from around the world to dive on one of Germany's infamous submarines. |

|

| U-352 off Morehead City, NC (July 1992, film) | |

| U-701 (sunk July 7, 1942) | |

|

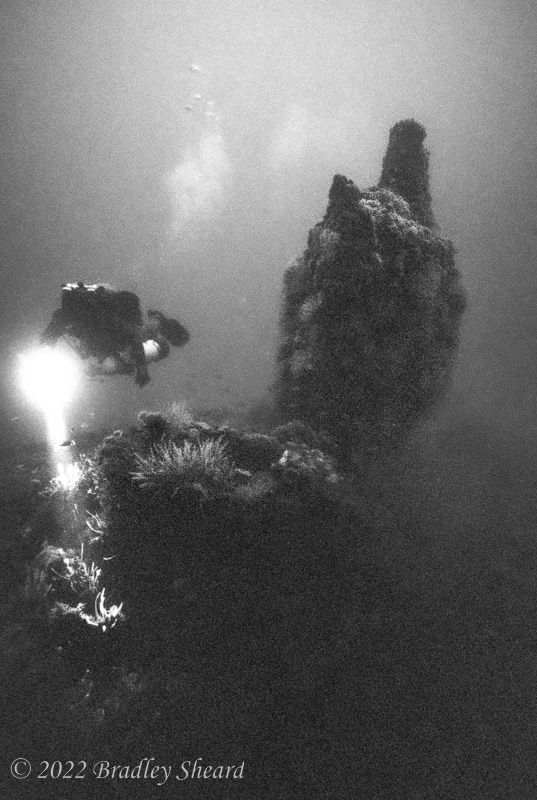

To the German sailors trapped inside a sunken submarine off Cape Hatteras in 1942, their miraculous escape must have seemed like an answered prayer. As circumstances unfolded, however, their break for freedom was much like the proverbial jump from the frying pan into the fire. Two groups of men had clawed their way out of U-701 after she was sent to the bottom, but those destined to survive would spend the next 49 hours drifting in the Gulf Stream, covered in oil and baking in the hot sun with no food and no water. For most it would be a harsh death, but for Kapitanleutnant Horst Degen and six others, salvation would come from the very enemy that had condemned their boat to the deep. U-701 was a 500-ton type VIIC boat whose range was a bit of a stretch for operations in American waters. After a slow crossing designed to save fuel, Degen and crew secretly laid a minefield outside the entrance to Chesapeake Bay that later claimed several unsuspecting ships as victims. A few days later, U-701 was the victor in a daring gun-duel with the armed trawler YP-389, which was sent to the bottom; a week after that Degen put a single torpedo into the tanker British Freedom, quickly drawing the wrath of USS St. Augustine's depth charges. Both the U-boat and the torpedoed tanker managed to survive their respective encounters, but the following day Degen drew serious blood when he put a torpedo into the big tanker William Rockefeller, setting her cargo of fuel oil ablaze. Crippled but not yet finished, the Rockefeller continued to burn into the night, allowing U-701 a chance to finish her off after sunset—but the submarine commander's luck was destined to change shortly. Nine days later an Army A-29 bomber was on routine patrol near Cape Hatteras when the pilot, Second Lieutenant Harry Kane, sighted U-701 through broken clouds, running on the surface with decks awash. Driving in on the rapidly diving U-boat from astern, Kane dropped three depth bombs, two of which hit home alongside the conning tower. Inside the submarine, Degen admonished his executive officer, who had first spotted the attacking aircraft: "You saw it too late." The two bombs smashed instruments and tore open the pressure hull. Water poured in through the breaches and within two minutes the control room was nearly flooded. The men inside managed to re-open the conning tower hatch as the submarine headed for the bottom, and 18 men escaped, popping to the surface in the middle of rising bubbles of air and oil. A second group of Germans escaped from the bow compartment a few minutes later, through the torpedo loading hatch. Seeing the men floating helplessly in the sea below him, Kane dropped four life vests and a raft, all he had on board his aircraft, and circled the area for two hours as he tried to summon help before finally running low on fuel and heading to base. The following two days were a nightmare to the survivors. The stronger saw their comrades drown one by one. Some went mad before dying. Degen later recalled that one of his men, before dying, said goodbye to him: "I'm taking leave of you. Please remember me to my comrades." "As darkness descended we consoled ourselves with hope in the 'morrow. A few of us were ready to give up, but these we cheered up, so that we were all still together when it became light again." After spending another day and a second night afloat in the open ocean and watching more men succumb to the sea's cruelty, seven survivors were finally spotted by a Navy blimp and rescued by a Coast Guard seaplane, becoming prisoners of war. U-701 has long been an elusive wreck site for a number of reasons. The wreck was discovered by Uwe Lovas, and the exact location remained a closely guarded secret for many years. The wreck's coordinates eventually became known to charter boat captains, but lying on the Diamond Shoals the site is often swept by strong currents, making diving challenging. Those same currents also serve to both bury and unbury the remains in constantly shifting underwater sand dunes. |

|

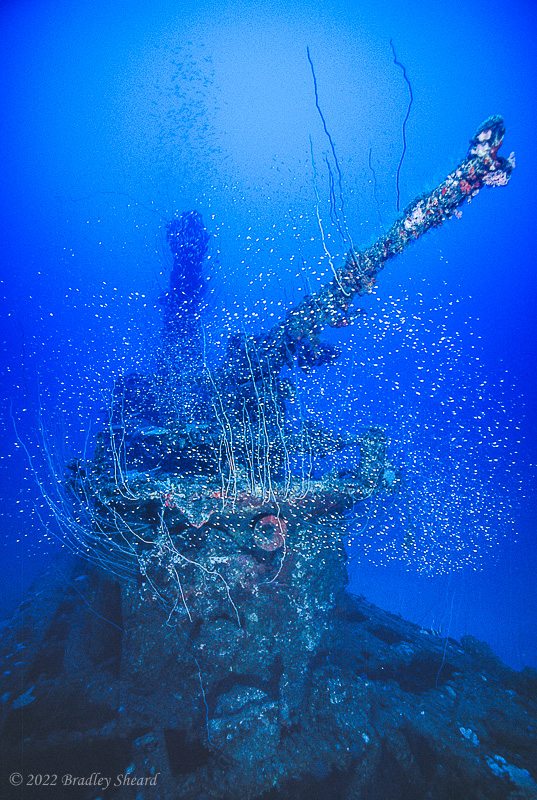

| U-701's bow rising above the shifting sands of Diamond Shoals (June 2014, digital) | |

| U-550 (sunk April 16, 1944) | |

|

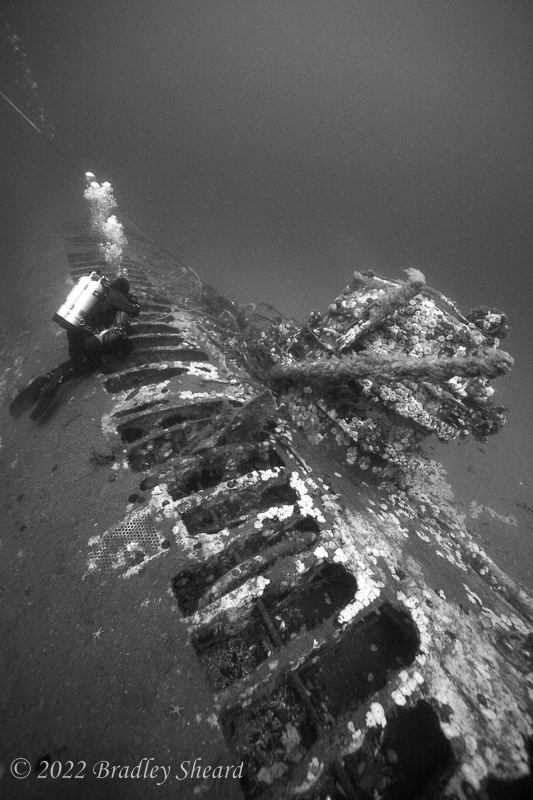

The SS Pan Pennsylvania was a massive tanker--501 feet long and 10,017 gross tons. She left New York on April 15 as part of convoy CU-21, bound for Britain with a cargo of 140,000 barrels of gasoline and seven aircraft lashed to her deck. By 7:00 am the next morning the ships were south of the Nantucket lightship, where they began to form-up the convoy for the Atlantic crossing; Pan Pennsylvania took the second slot in the left-hand column. At 8:05 am an explosion rocked the tanker; according to Captain Delmar Leidy, "She was hit by one torpedo which struck her on the port side in the way of #8 tank. . . Immediately after we had been torpedoed, I went to the port wing of the bridge to inspect the damage. I observed a large hole, but no fire had broken out at that time. The vessel had a heavy list to port, approximately 30°. . . The ship was then making about 13 knots. I then proceeded to the starboard wing of the bridge and found that some of the crew had become panicky and had attempted to launch #3 lifeboat without any order whatsoever. In so doing, they had capsized the boat, spilling all the men in it into the water." There were 81 men on board the tanker, including 31 armed guard to man the ship's guns, but the submarine responsible was nowhere to be seen. Captain Leidy quickly took control of the situation, "I then had the vessel searched for men who might be trapped; the Chief Engineer inspected the engine room and reported back to me stating that he had found gas in the bilges and that it was on fire." A tanker loaded with gasoline and on fire was not a good place to be, and Captain Leidy realized it was time to leave. "About 8:20 am I ordered #1 lifeboat away at which time the ship was dead in the water and had been so for several minutes. In the meantime, the Chief Engineer again reported to me, stating that the fire in the engine room was out of control." The ship was quickly abandoned, the men taking to the lifeboats and rafts, and 56 survivors were picked up by the escorts USS Peterson and USS Joyce about an hour later; 25 men were missing. Leidy's ship was gone: "The last I saw of the Pan Pennsylvania, she was on fire which covered the whole superstructure and she had at that time a port list of 30°." The offending U-boat was U-550, under command of Klaus Hanert; retribution for the sinking was swift. Three of the convoy escorts converged on the torpedoed tanker; while USS Peterson and USS Joyce picked up survivors, USS Gandy provided cover. Shortly after the victims of the attack were safely aboard the escorts, Joyce obtained a solid sound contact. Closing in she delivered a shallow-set depth charge attack; seven minutes later the submarine surfaced. All three escorts immediately poured accurate fire onto the sub. As the escorts converged on the surfaced submarine, Gandy rammed her aft of the conning tower. The Germans abandoned ship and a muffled explosion was heard aboard the U-boat. Twelve of the submariners survived and were taken prisoner, while the U-boat sank stern first. Three German bodies were found adrift with escape lungs and picked up by patrol boats over the next few weeks, the last remnants of those aboard U-550 who did not survive, and who were apparently left at the scene of battle by the American escorts, who's duty lay in protecting the remainder of the convoy. U-550 was discovered lying in 330 feet of water south of Nantucket on July 23, 2012 by the crew of the dive boat Tenacious. For a more complete accounting of this discovery and the exploration of the wreck see |

|

| U-550 330 feet down off Nantucket (August 2014, digital) | |

| U-772 (sunk December 29, 1944) | |

|

U-772 was a type VIIC boat operating out of Trondheim, Norway late in the war. She only made two war patrols before being lost. Working in the English Channel, particularly this late in the war, was extremely hazardous. Two days before Christmas on December 23, 1944, U-772 attacked two separate convoys in the Channel, sending one ship from each to the bottom. Five days later, on the 28th, she sent the infantry landing ship Empire Javelin to the bottom near Cherbourg, France. The following day would be the bold U-boat's last, however. Attacking yet another convoy on December 29th, KL Ewald Rademacher damaged two ships, the steamships Black Hawk and Arthur Sewall. As U-772 was withdrawing from the attack, her periscope and schnorkel were spotted by a Wellington patrol airaft of the Royal Canadian Air Force, equipped with a Leigh Light "on the calm sea in the moonlight". Six depth charges were dropped on the submarine, sending the boat and her 48 crewman to the bottom of the English Channel--there were no survivors. In July 1999, I had a chance to dive this wreck lying in 180-feet of water on the bottom of the English Channel. The submarine lies listing 45° over to starboard with a large hole evident in front of the conning tower, surely from the depth charge attack. The periscopes, aerials and diesel vents were all in place on the conning tower, as were four escape canisters on the port side of the foredeck. She was remarkably intact, but it was difficult to capture the scene in those pre-digital photography days in such dark conditions. The best images I was able to get were shot on Kodak TMAX 3200 black and white film, push-processed to ISO 25,000! Note that the identification of this wreck was tentative at the time I dived it. |

|

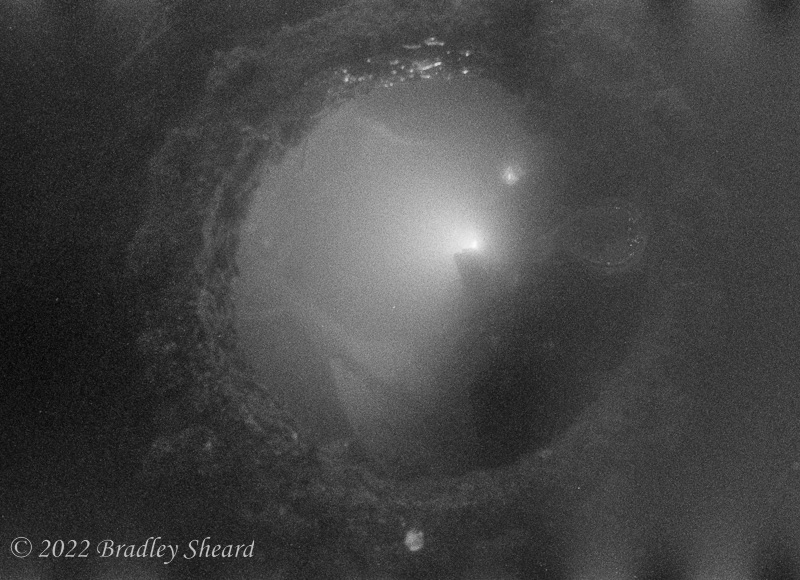

| U-772's conning tower on the bottom of the English Channel (July 1999, film) | |

| U-869 (sunk February 11, 1945) | |

|

On September 2, 1991, a group of divers aboard Captain Bill Nagle's boat Seeker first dived a set of hang numbers 50 miles off the New Jersey coast--what they found was a World War II German U-boat that history said shouldn't be there. Official war records documented only ten U-boats sunk in the Eastern Sea Frontier, and while a few had not been positively located, the closest recorded sinking was more than 100 miles away--far too distant for a navigation error. The identity of this mysterious submarine quickly became an obsession for a small group of wreck divers who sought clues in both historical archives and on the ocean bottom. On November 6 1991, barely two months after the submarine had been discovered, John Chatterton recovered a knife with the name "Horenburg" carved into the handle. German records showed that a radio operator named Martin Horenburg had served aboard the U-869, but also indicated that this boat had been sunk off Gibraltar in February 1945. Soon after this discovery, however, further archival research unearthed top secret Allied radio intercepts from the war indicating that U-869's original patrol assignment was the New Jersey coast; after rounding Iceland she was re-directed to a patrol area off Gibraltar, but never acknowledged that change in orders. In August 1997, six years after the submarine had been discovered, John Chatterton, assisted by John Yurga, Pat Rooney and Richie Kohler, made a difficult penetration into the electric motor room and recovered a spare parts box with a plastic tag marked "U 869"--the ID was official. In 2004 Harold Moyers discovered a previously overlooked U-boat attack record only 4.5 nautical miles from the wreck now known to be U-869. On February 11, 1945, the Coast Guard crewed destroyer escort Howard D Crow was guarding UK-bound convoy CU-58 when she obtained a strong sonar contact with slight movement. Her crew launched a hedgehog attack and obtained "explosions beneath (the) surface." This was followed by two depth charge attacks, bringing up "air bubbles and oil slick." The USS Koiner joined the attack and dropped three more rounds of depth charges. Koiner lowered a whale boat to investigate; finding some diesel oil but a stationary target, the target was officially classified "non-sub." According to the convoy escort report, "Koiner's report of non-sub was made on the basis that there was no movement, that any apparent movement previously was caused probably by current and that repeated attacks on the still target continued to bring oil to the surface, indicating the target to be a wreck, submarine or otherwise." |

|

| U-869's conning tower lying on the bottom alongside the submarine's demolished control room (July 2005, film camera on tripod) | |

| U-1195 (sunk April 6, 1945) | |

|

Late in the war, German U-boats did not have a good life expectancy; being sent to the confined waters of the English Channel did not enhance a boat's chances of survival. U-1195 left Bergen, Norway under command of Ernst Cordes in February 1945 bound for the English Channel. A new type VIIC boat, U-1195 was equipped with a schnorchel, which it likely used for most of the 27-day passage from Norway to the Channel. On March 21st he fired a torpedo at the American Liberty ship James Eagan Lahyne, likely scoring a hit that damaged the vessel. Two weeks later he was still prowling the Channel, and on April 6 he ran across a small coatal convoy, firing several torpedoes, and managed to sink the large British freighter Cuba. U-1195 tried to hide on the bottom, but the depth was only 100 feet, and the convoy escorts had no trouble locating her, firing both depth charges and hedgehogs. The attack put a hole in the U-boat's bow and water poured in rapidly. Too heavy to surface, the U-boat's crew attempted a submerged escape; eighteen of the crew were successful and were picked up by the attacking escorts, but the other 32 men were lost. There were apparently some salvage attempts by the Royal Navy. Today the U-boat lies heeled over to starboard with the conning tower blown off or missing, and a large hole forward of where the tower should be. We made a dive on her remains in 1999, but the visiblity was absolutely horrible--5-8 feet according to my notes, making any real photography almost impossible! |

|

| A ridiculously bad photograph looking into the hatch of U-1195 (July 1999, film) | |

| U-853 (sunk May 5-6, 1945) | |

|

It is difficult to imagine anything more futile than dying on the last day of a war in which your country surrenders unconditionally; when that fate befalls the entire crew of a submarine it could be called tragic--although probably not by the crew of the American collier Blackpoint. The ancient ship had been built in 1918, and was chugging along at 8 knots, well inshore, only five miles off Point Judith, Rhode Island in 17 fathoms of water on May 5, 1945. At 5:40 in the afternoon a single torpedo materialized from the sea and blew the stern off the old ship. She quickly began to sink by the stern and Captain Charles Prior ordered the crew to abandon her; 34 of the 46 men on board survived the sinking, but 12 went missing and were presumed lost. Helmut Fromsdorf had brought his type IXc/40 schnorchel submarine across the Atlantic in the waning days of a war that his country was clearly losing. U-853 left Norway in late February and probably arrived off the American coast in late April, likely sinking the patrol craft Eagle 56 off Portland, Maine before heading south and entering Rhode Island Sound. Undoubtedly operating submerged with schnorchel the entire time, it is unlikely she picked up Admiral Donitz's May 4 broadcast to all U-boats ordering an end to hostilities. Unfortunately for Fromsdorf, the prospects for a U-boat caught in shallow water this late in the war were not good. Two hours after Blackpoint was torpedoed the destroyer Ericsson, destroyer escorts Atherton and Amick, and the CG patrol frigate Moberly, arrived on the scene and set up a patrol line to hunt down the offending submarine. Atherton quickly picked up a sonar contact and began the attack with a full pattern of 13 magnetic depth charges, resulting in one explosion. This was quickly followed up with hedgehog attacks, each producing explosions, after which the sound contact was lost. The ships continued to search the area, but it was nearly three hours and almost midnight before contact was regained. More attacks with both hedgehogs and magnetic depth charges followed, bringing up oil, air bubbles and bits of broken wood. As the target appeared stationary on the bottom, attacks were suspended and the ships continued to search the area until dawn. Just after sunrise the attacks resumed. The water was so shallow that the attacking ships were repeatedly damaged by their own weapons explosions. For the next several hours Ericsson, Moberly and Atherton took turns making combined hedgehog and depth charge attacks. As each vessel completed its attack run, it would move off the scene and make repairs, while the next ship in line would drop its ordinance. As the three ships pounded the bottomed submarine with attack after attack, more and more debris, oil and air rose to the surface. A blimp dropped a sonobuoy, picking up what was described as a "rhythmic hammering on a metal surface, which was interrupted periodically." That afternoon a diver was sent down, finding the submarine's pressure hull split, bodies evident, and confirmed her identity as U-853. The following day, Germany signed unconditional surrender documents, ending the war in Europe. |

|

| Looking down into the U-853's conning tower hatch, showing periscope casing and corroded ladder (July 1994, film) | |