Anatomy of a Steamship Wreck

|

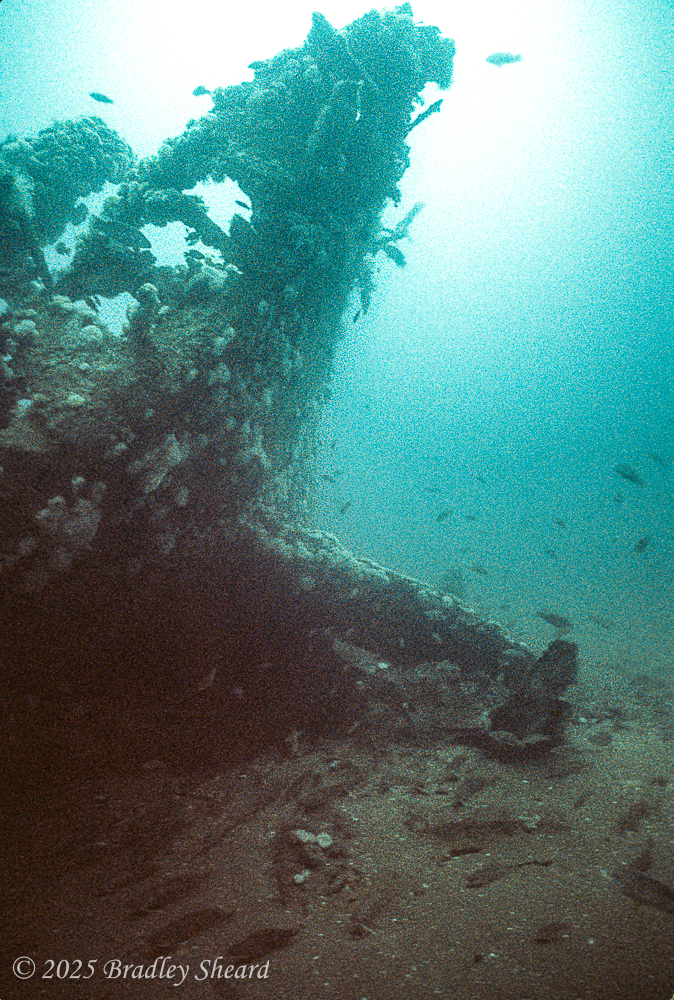

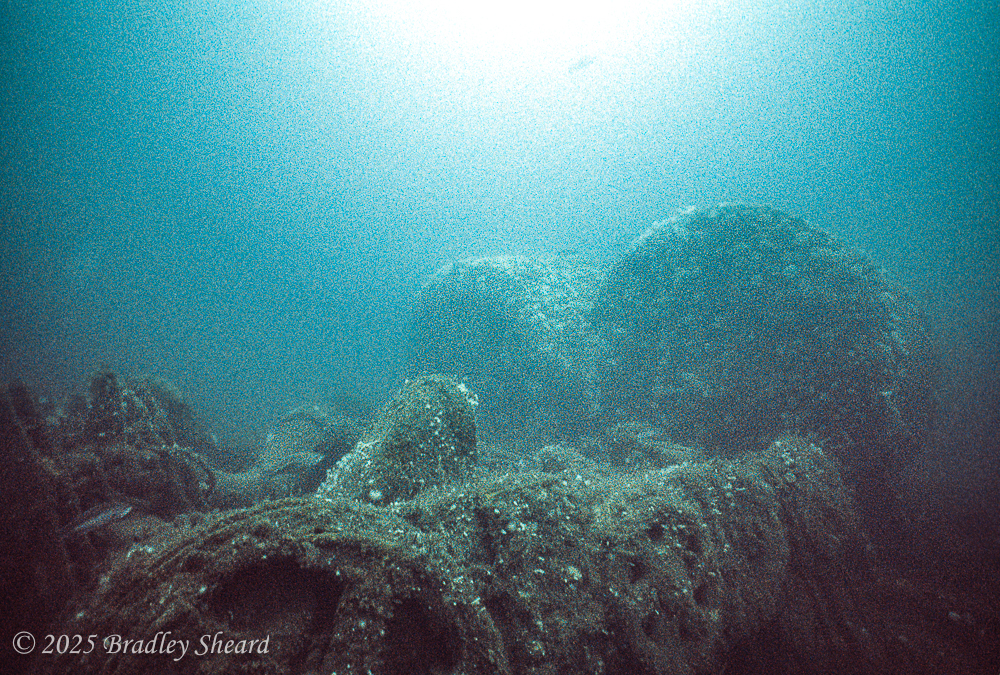

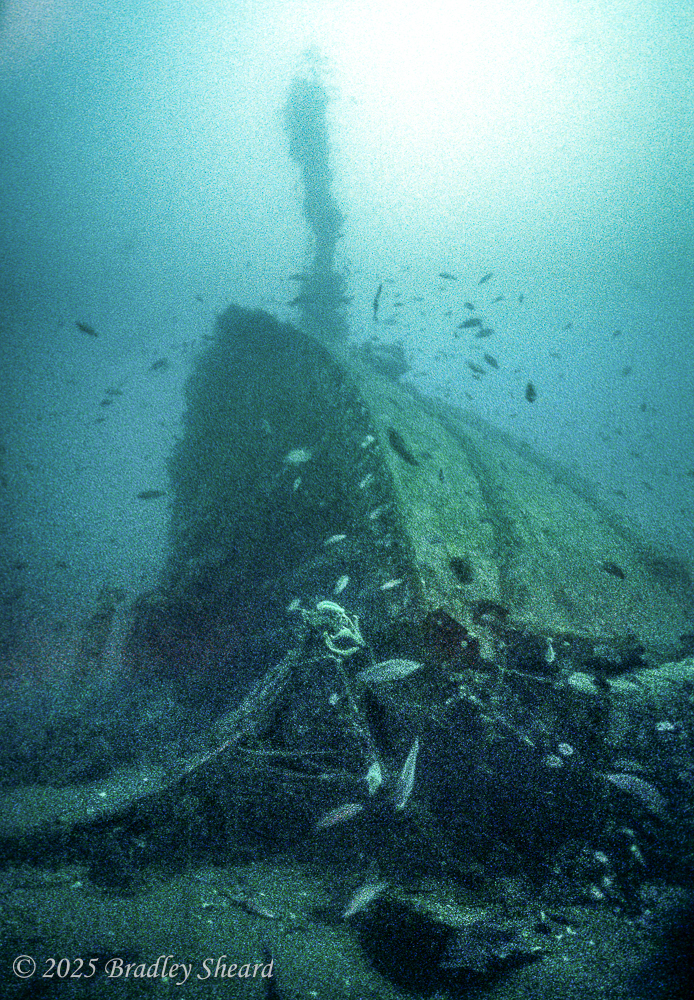

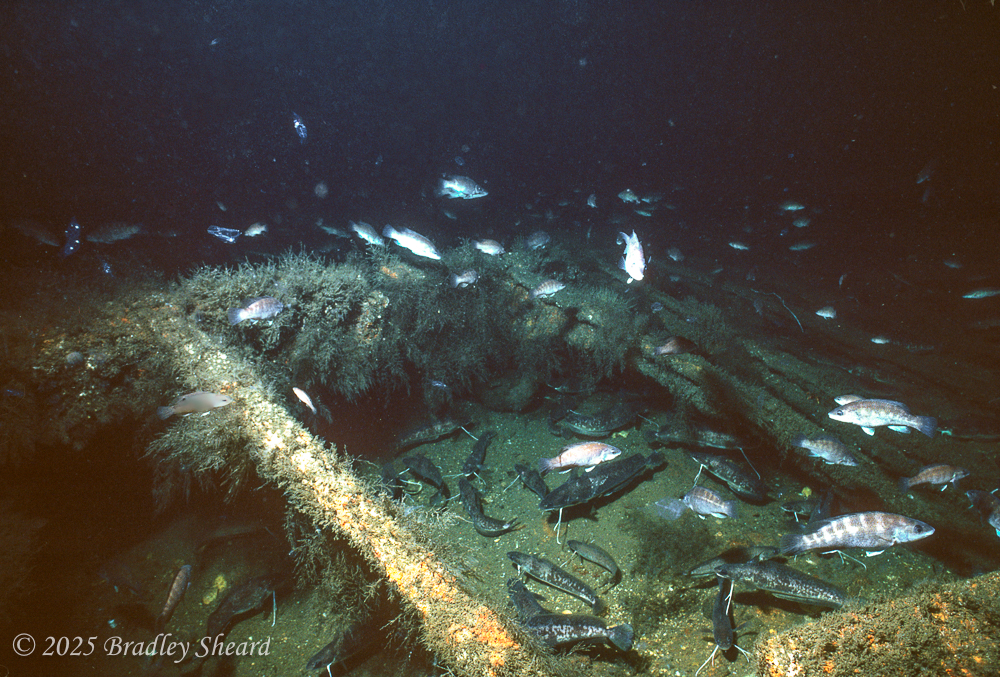

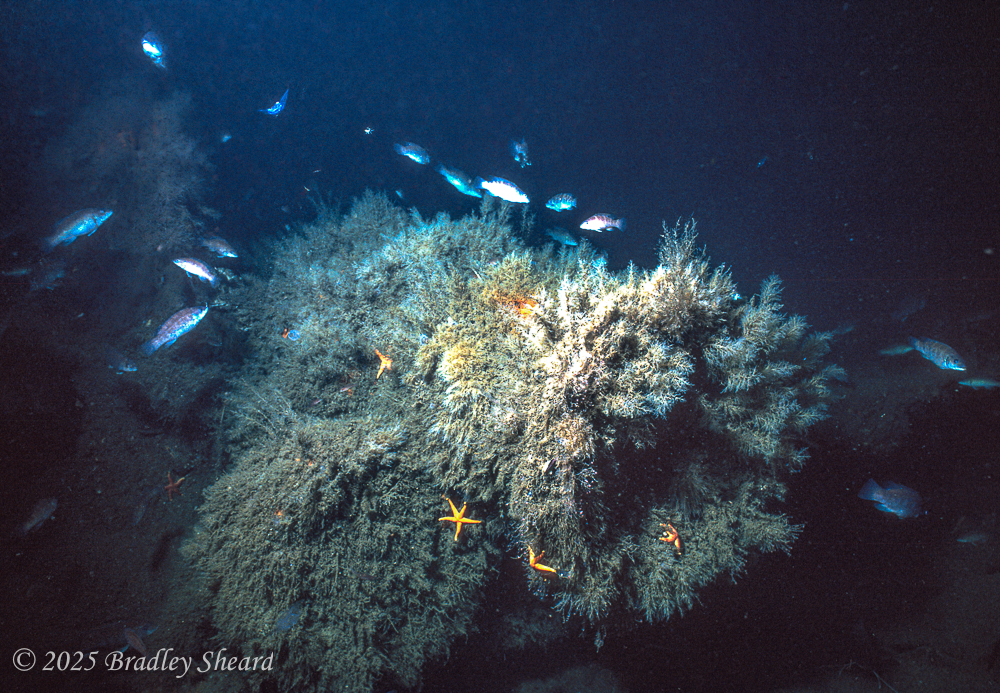

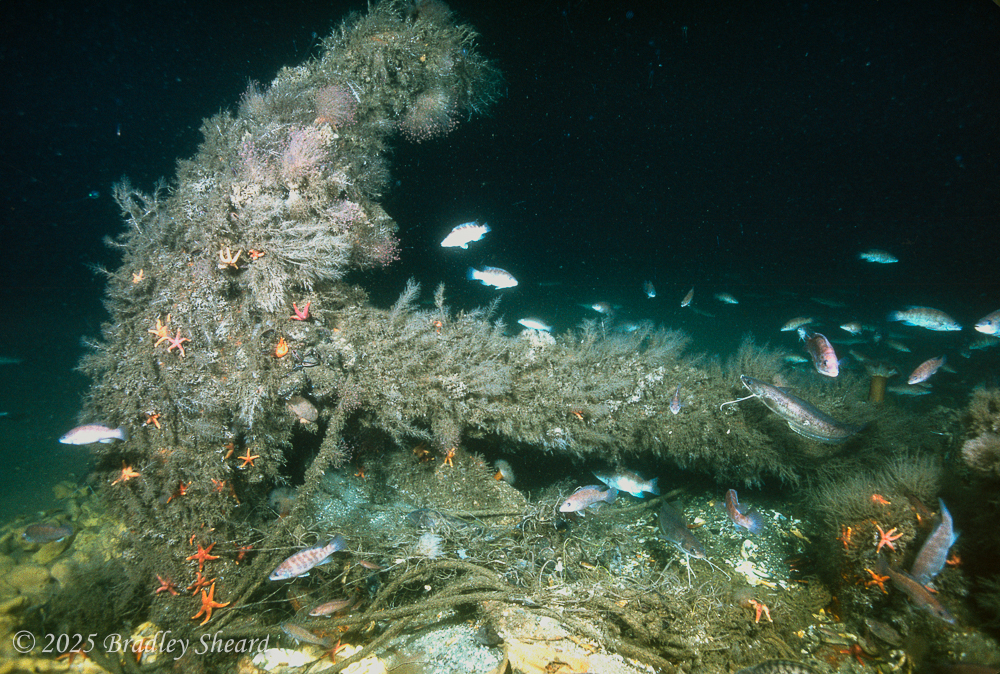

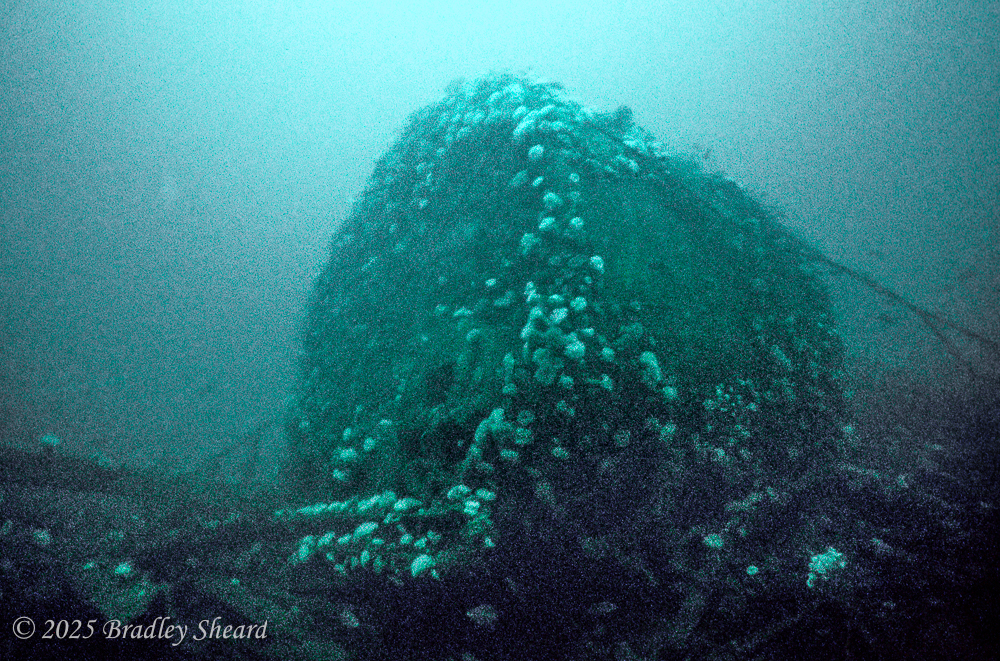

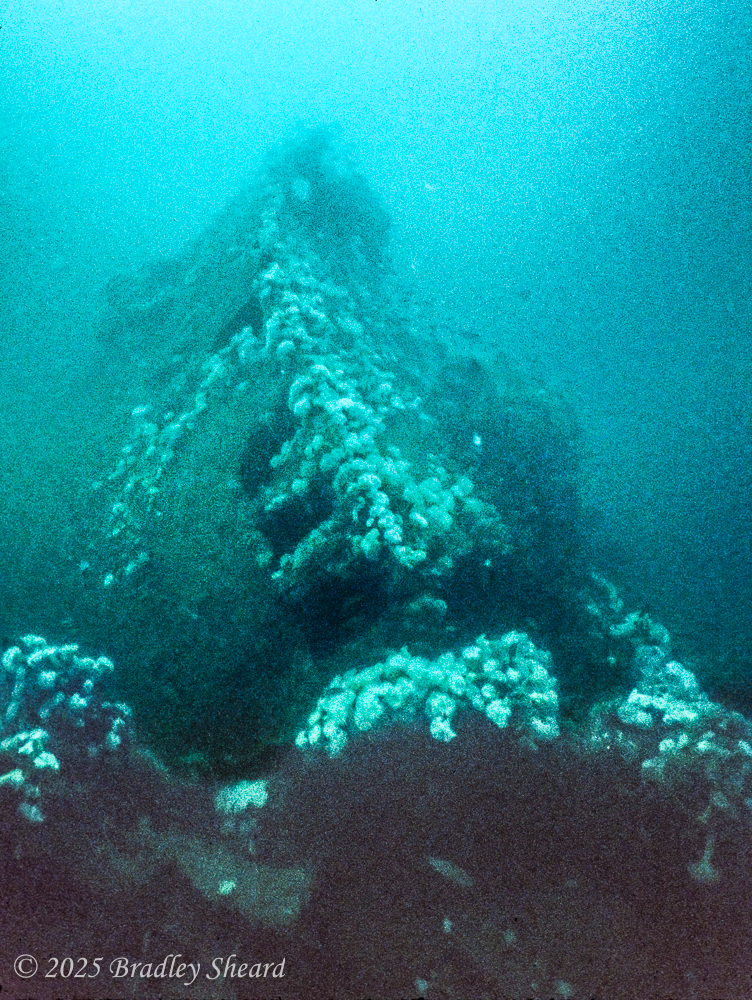

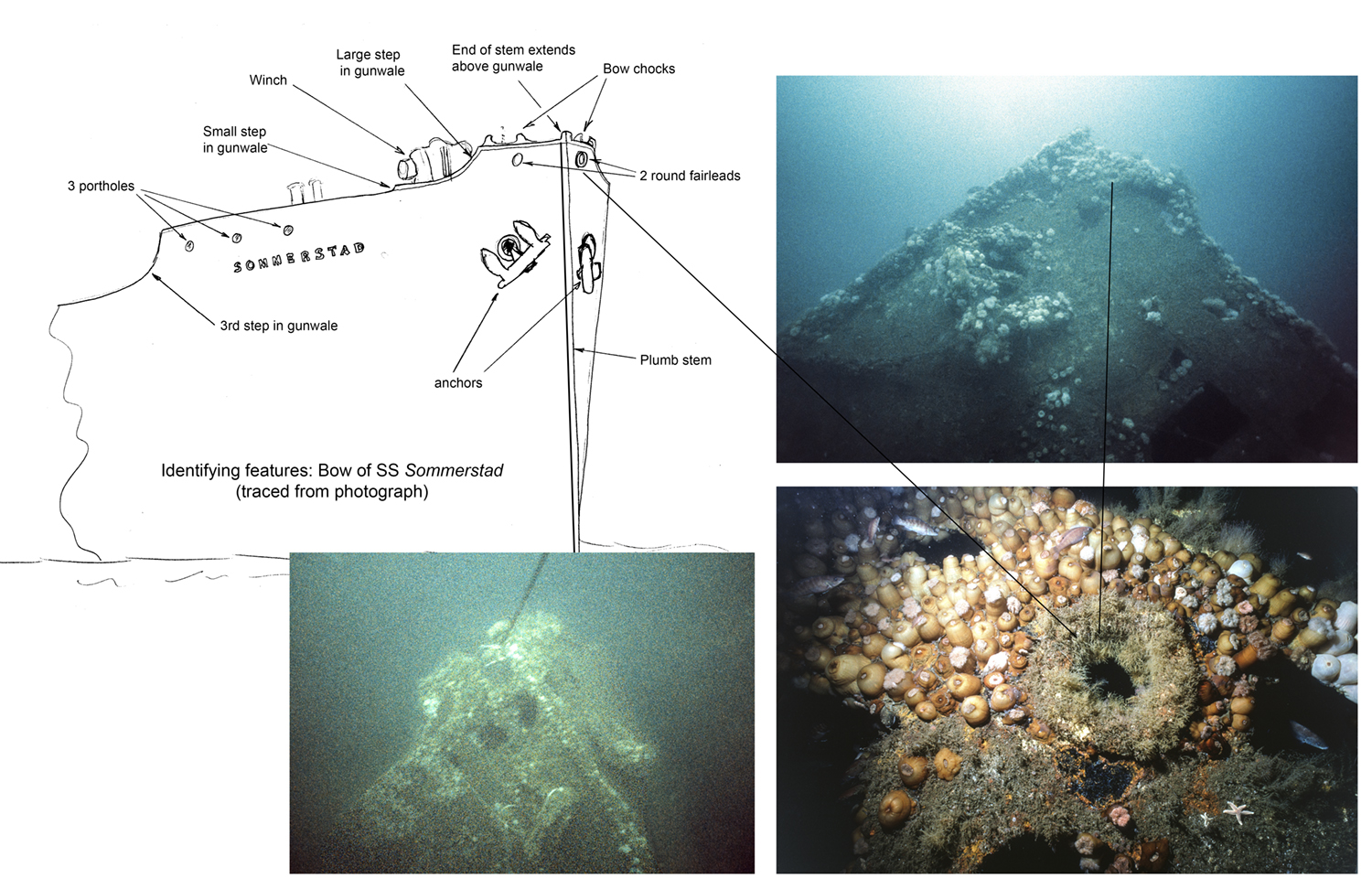

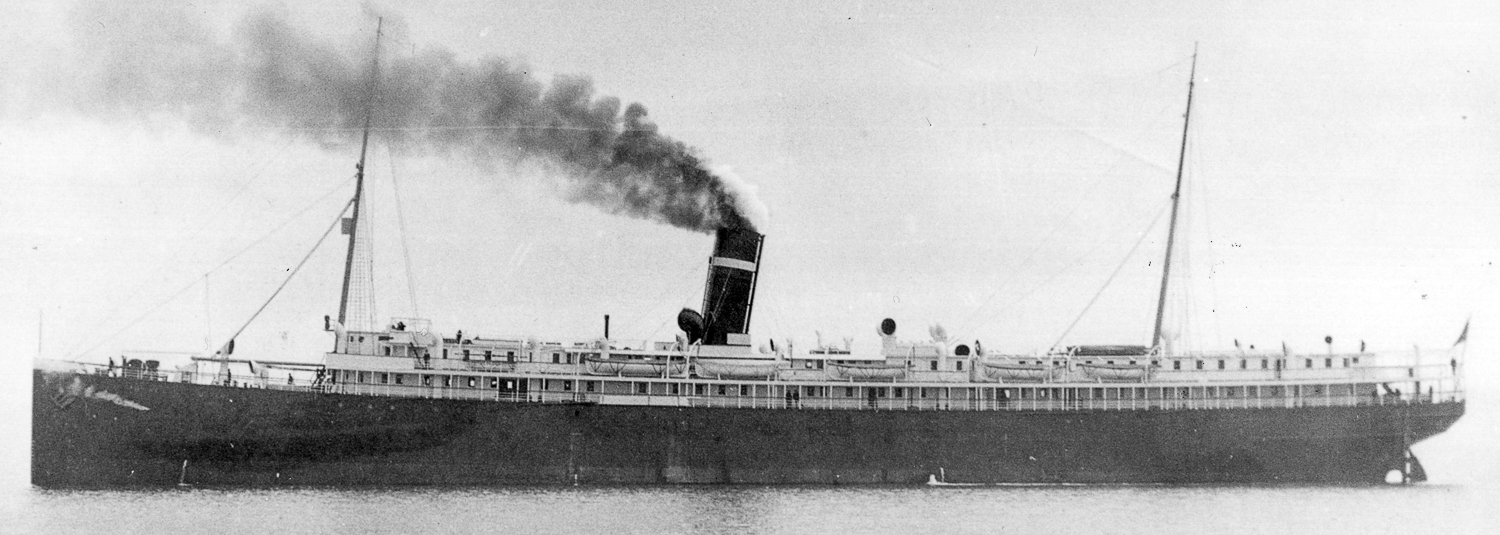

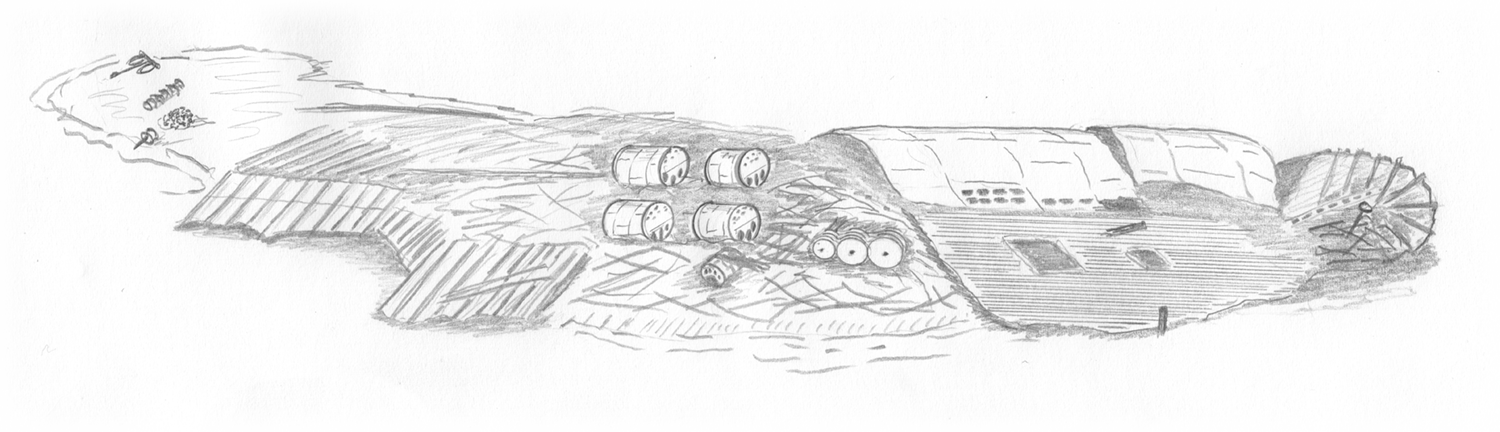

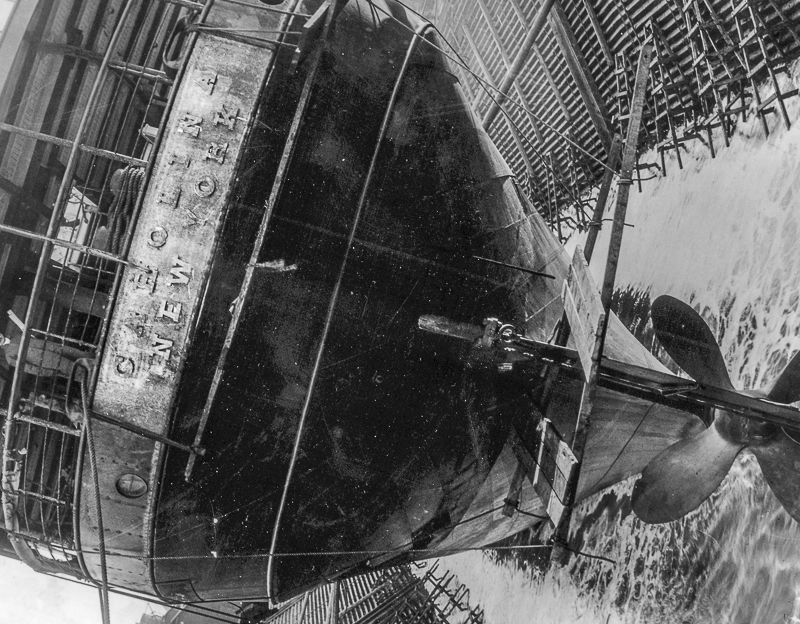

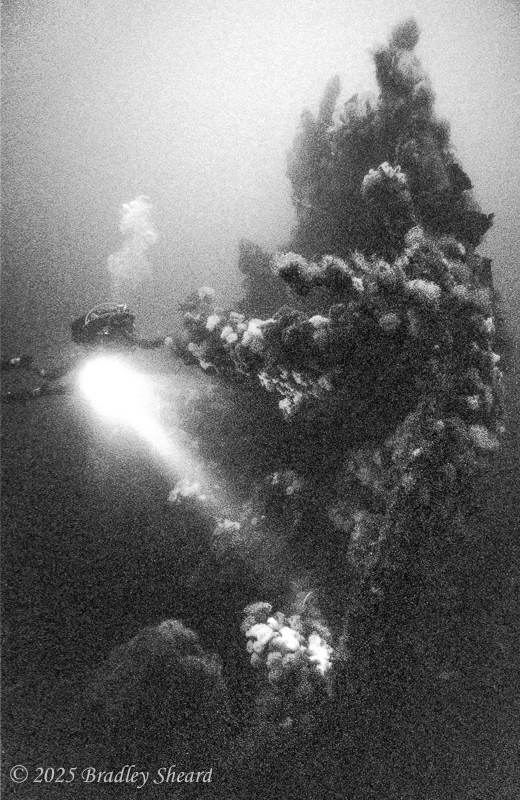

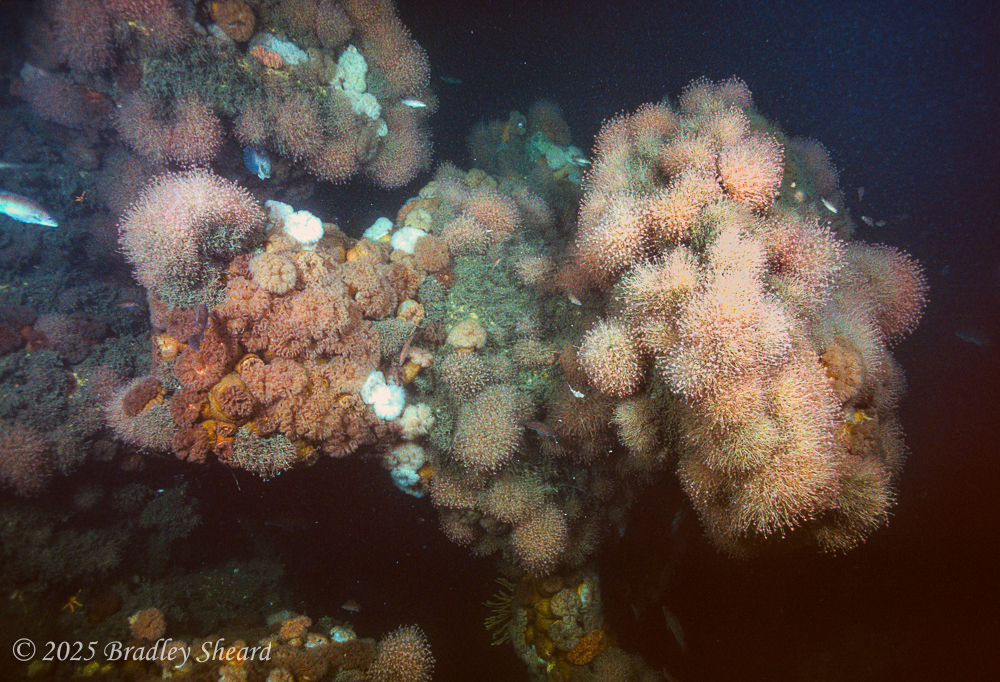

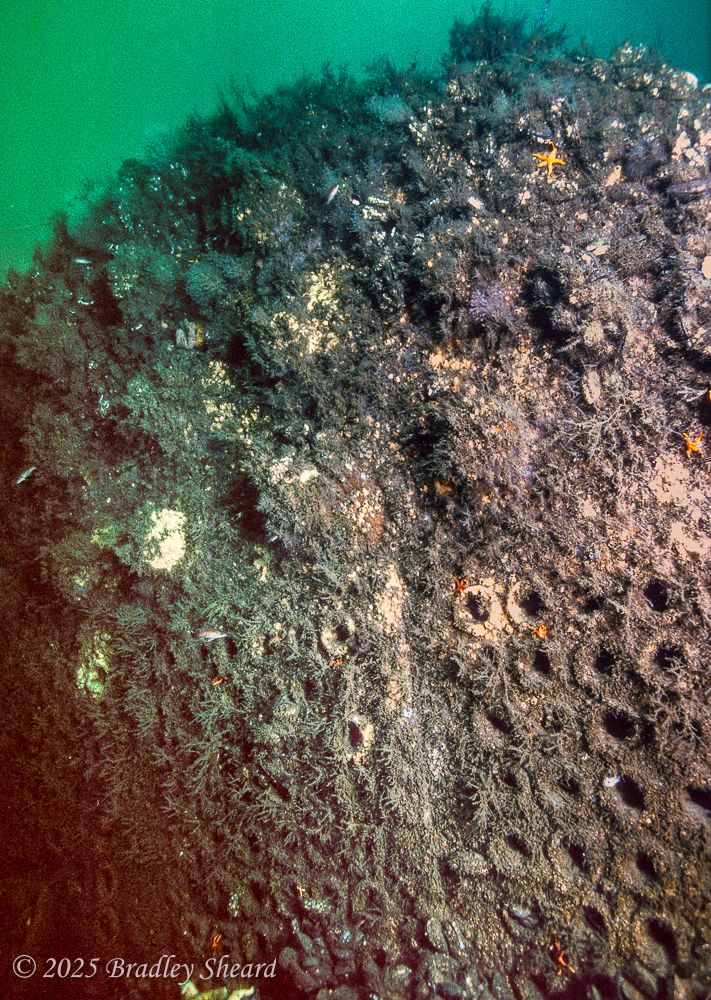

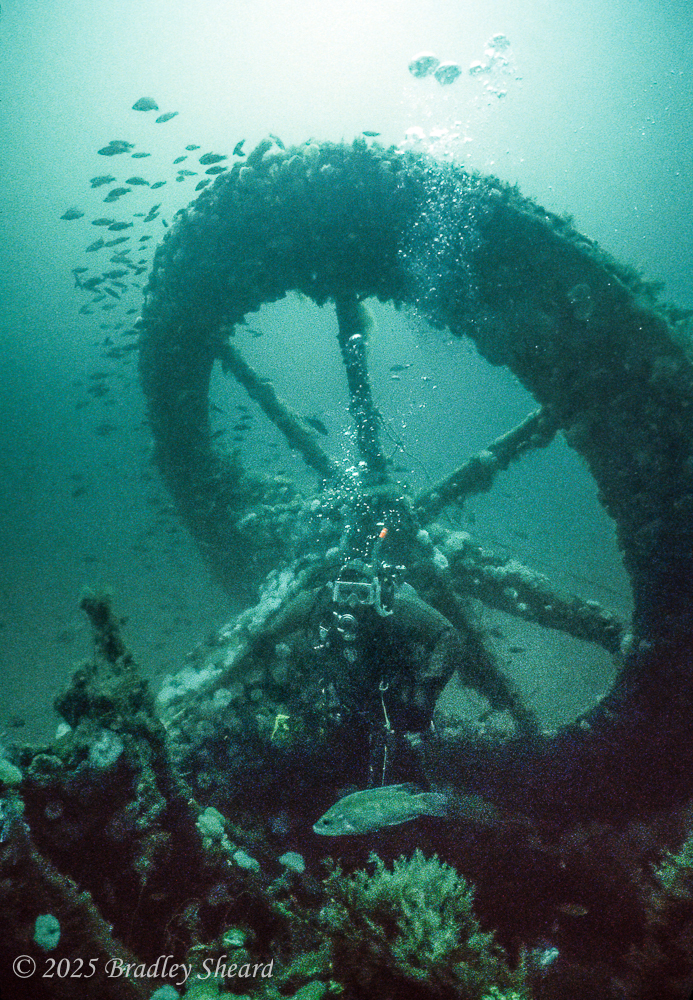

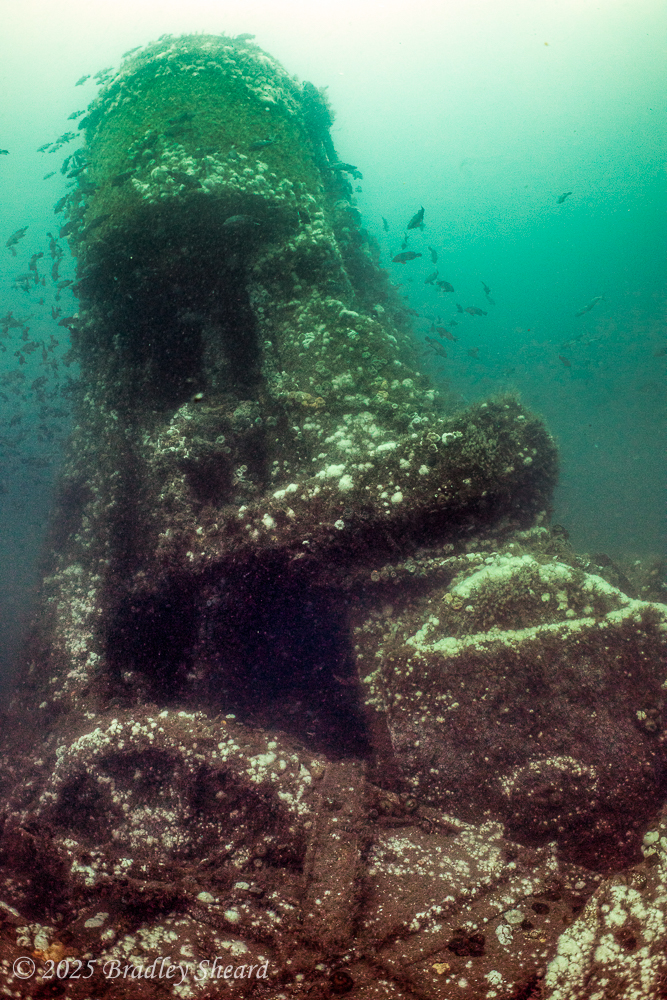

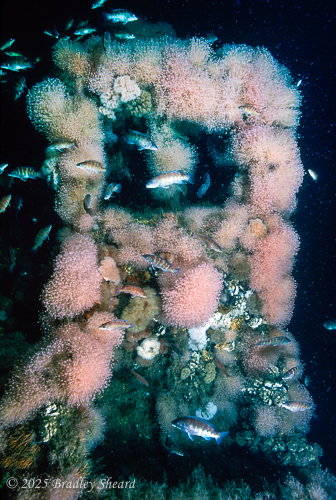

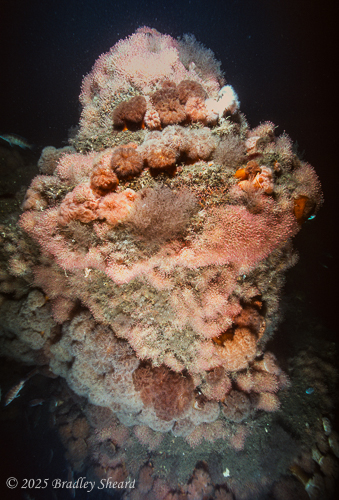

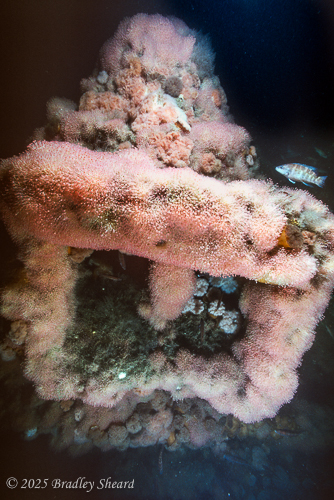

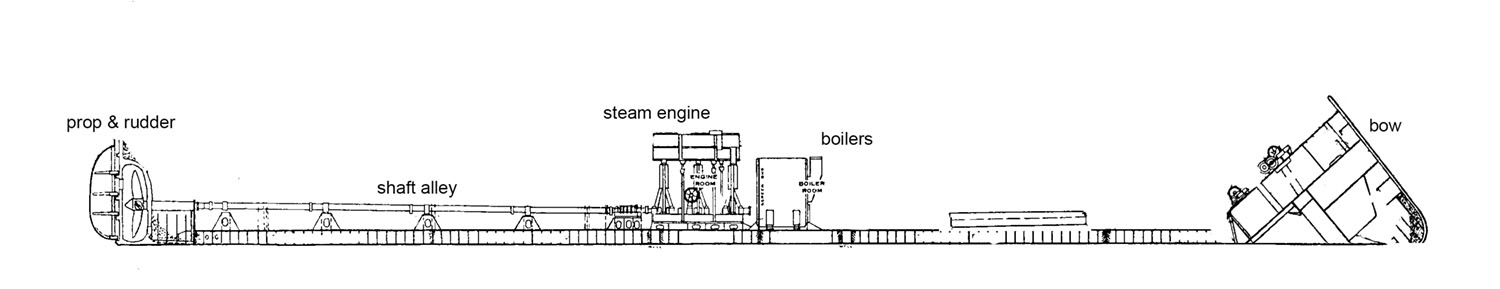

As steam-powered ships matured and largely replaced commercial sailing vessels, their designs coalesced into fairly common configurations. There were, of course, variations--one of the biggest being engine placement. Some designers placed the engine and boilers midships, while others placed them in the stern, shortening the length of the propeller shaft. When a ship like this sank, it might land upright on the bottom or on its side (except warships, whose top-heavy guns often made them land upside-down). Cargo vessels generally had wide, flat bottoms to maximize hold capacity, and these flat bottoms more often than not facilitated the ship initially settling upright on the ocean bottom. As years passed following their sinking, the corrosive effects of the ocean, as well as the constant forces imposed by storms and currents, took their toll on the vessel. The long expanses of flat hull plates along the ship's sides, as well as the decking, first began to sag; joints failed and eventually the sides of the hull fell outward onto the ocean bottom and the decks collapsed downward. The curved structures of the bow and stern are naturally stiffer and often lasted far longer, leaving fairly intact bow and stern sections on some wrecks. Inevitably, however, the hull eventually collapsed, leaving a few of the stouter parts of the ship still standing. The massively-built compound steam engine and boilers are generally the last parts to deteriorate, and in so many cases are the highest part of the wreckage still standing today. Since the original design of these ships was so similar, most steamship wrecks take on a common appearance on the bottom, with a largely collapsed hull broken down and partially scattered, while the engine, boilers, bow and stern generally form the highest part of the remaining wreckage. Below are a number of representative examples of steamship wrecks off the US East Coast, with rough sketches and a series of photographs showing how they appear today (or at least at the time I dived them), and some of the major features of the wreck site. |

|

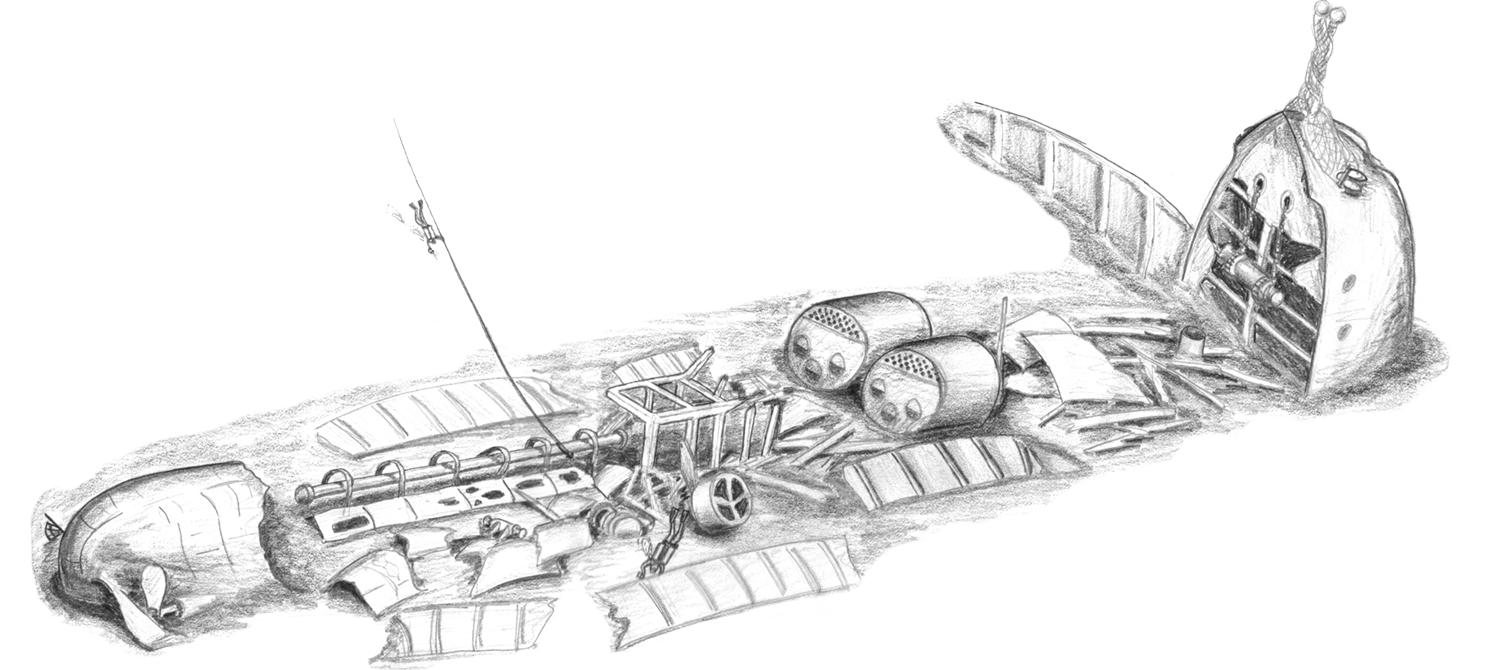

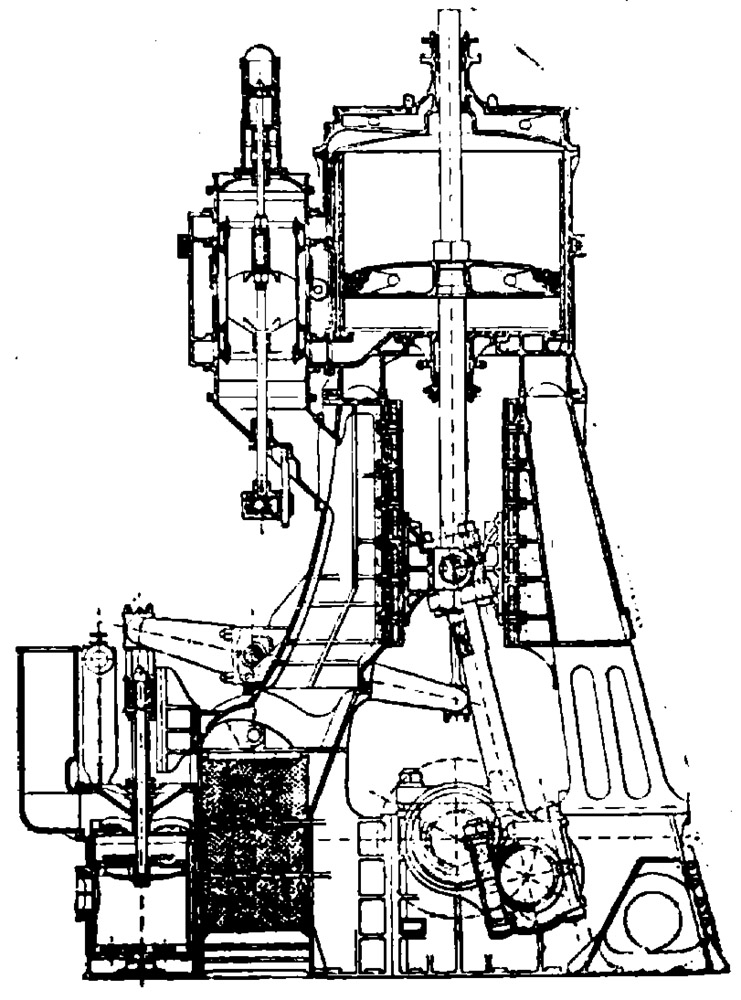

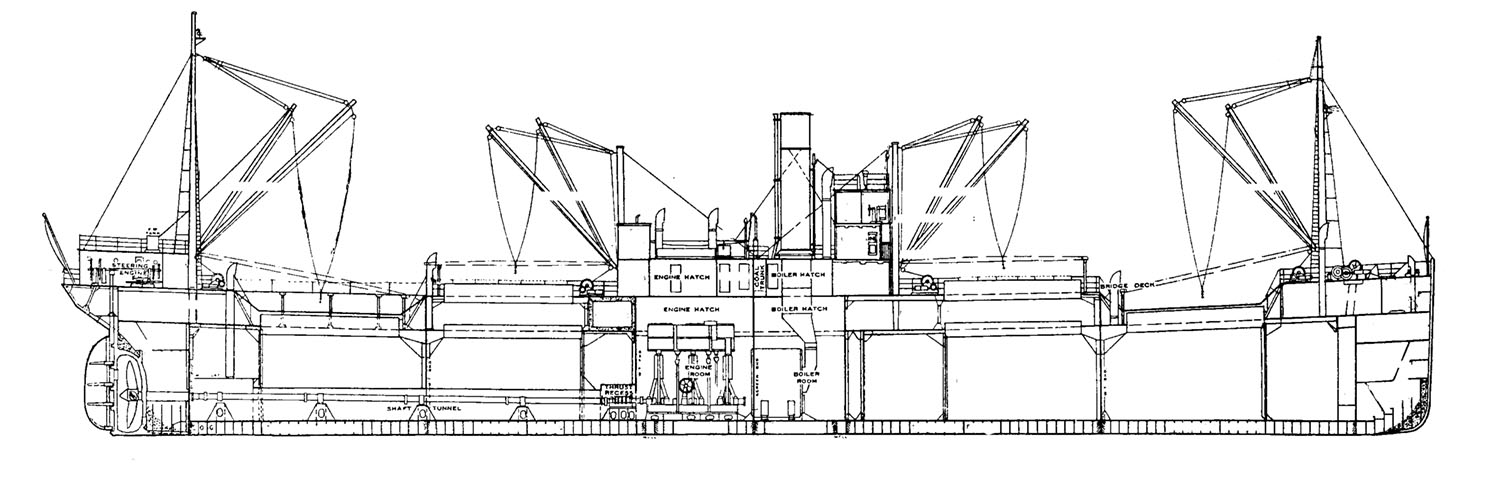

| Inboard profile plan of a generic steamship, with a triple-expansion steam engine and scotch boilers located midships | |

| |

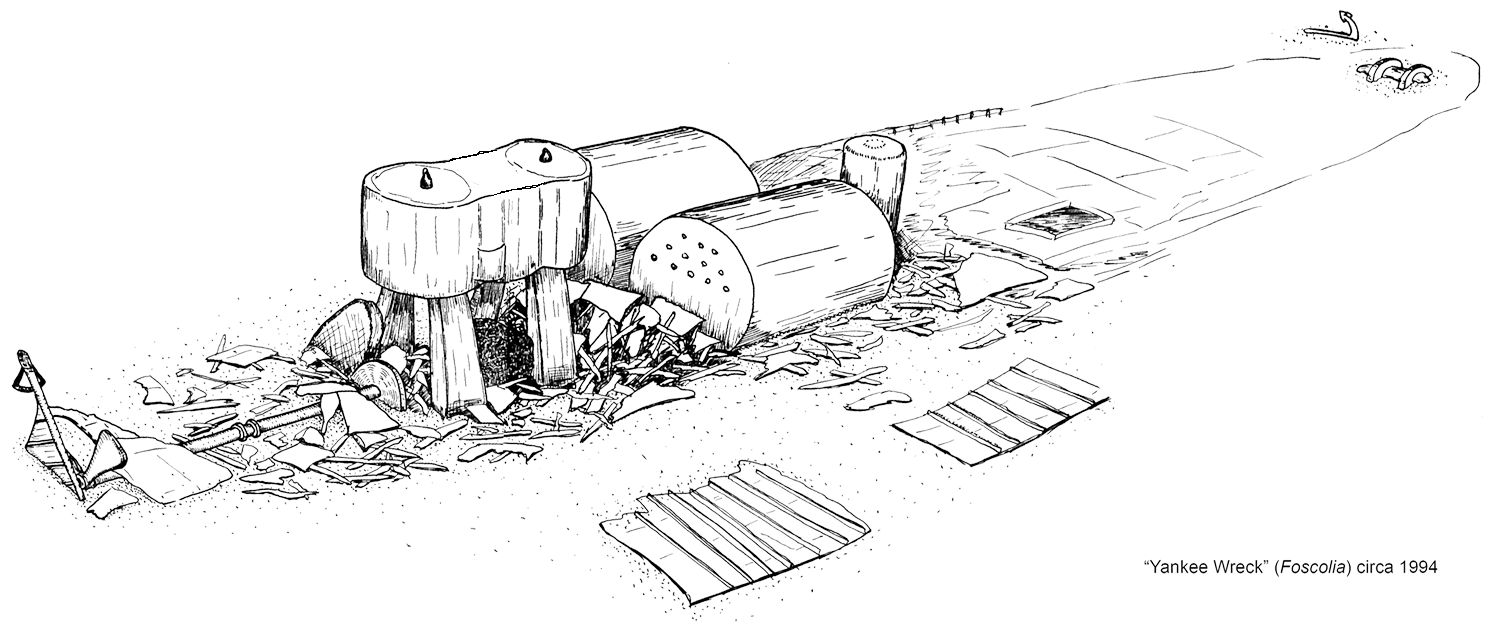

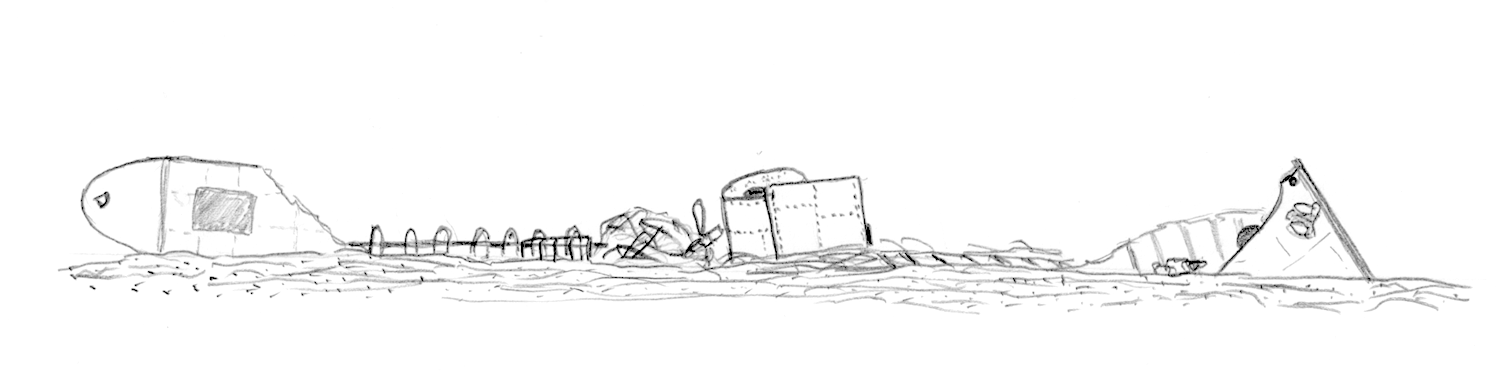

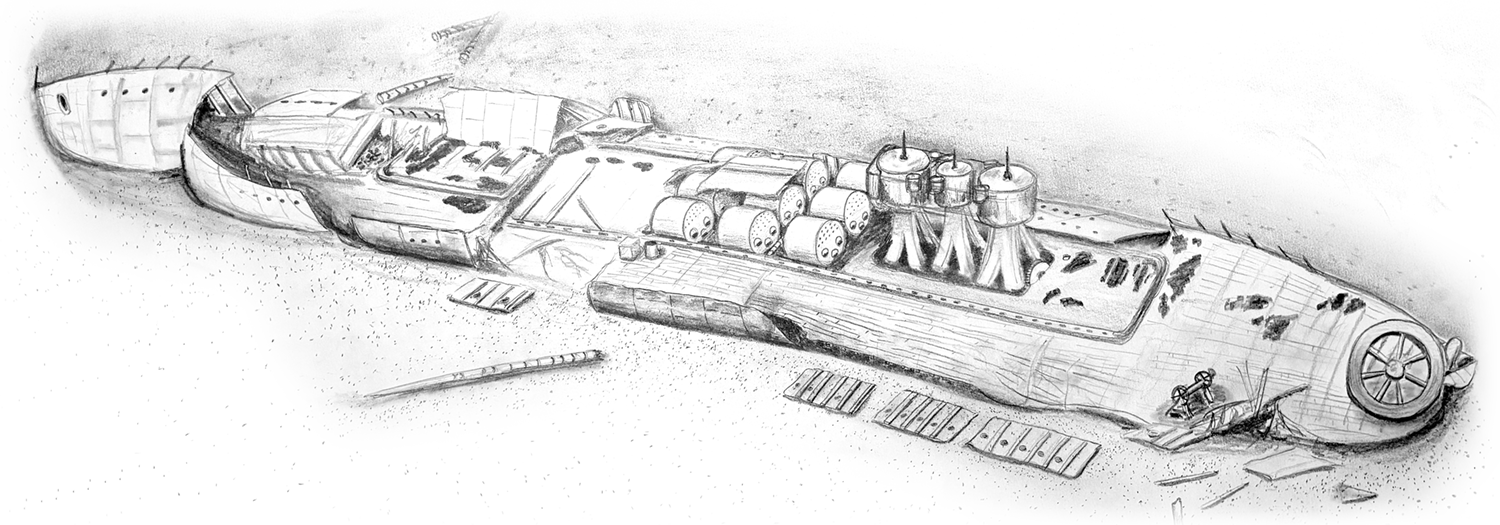

| A typical steamship wreck after 50+ years on the bottom. The hull has largely collapsed except the bow, but the engine and boilers still stand upright. |