|

|

| |

|  |

| Scenes of the Orkney Islands. The waterfront of Stromness (top); Standing Stones of Stenness (lower left); Colorful Stromness Harbor (lower right) | |

|

|

Orkney is a small island archipelago lying across the Pentland Firth from the northern tip of Scotland. Typical of Europe, the islands have a long and rich history, including the remains of ancient prehistoric cultures. Underground houses and stone circles can still be seen, such as the the Standing Stones of Stenness. The islands were ruled by the Vikings starting in the 8th and 9th centuries until 1468, when the islands were traded to Scotland, apparently to alleviate certain debts. The natural harbor of Scapa Flow became the northern naval base for the British Grand Fleet during World War I, with the intention of controlling the entrance into the North Sea. |

|  |

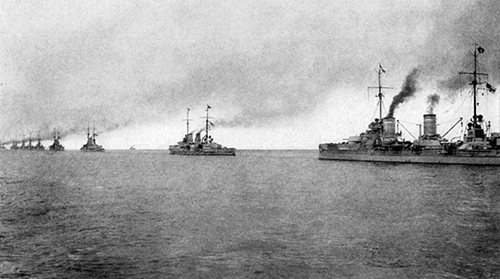

| The German High Seas Fleet surrendering (left); The fleet interned at Scapa Flow (right) | |

|

At the conclusion of the First World War, sometimes called The Great War, an armistice between the warring powers was signed in the early hours of November 11, 1918, taking effect at 11 am that same morning. Effectively a cease-fire agreement, three extensions were required before the Treaty of Versailles was finally signed on June 28 1919, officially ending the war. The terms of the armistice required Germany to surrender its entire fleet of U-boats, while the bulk of its High Seas Fleet was disarmed and interred at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. Manned by skeleton German crews and under the watchful eyes of the British Navy, the ships remained under German control while peace negotiations dragged on in Versailles, France for seven long months. When the terms of peace finally crystallized, Germany was given until June 21 1919 to sign the agreement. Admiral von Reuter, in command of the interned fleet, was isolated from home with no direct radio contact, and could only keep up with events through four-day old newspapers supplied by the British. Convinced the treaty would not be signed by the deadline and fearful that the British might take control of the German ships, he ordered his fleet scuttled on the morning of June 21, using pre-arranged signal flags flown over his flagship Emden. | |

|

|

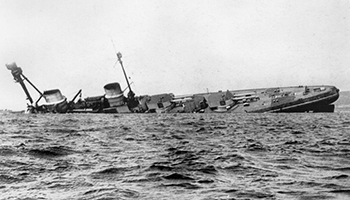

| Germany's High Seas Fleet being scuttled: (left-to-right) battlecruiser Derflinger, dreadnought Bayern and battlecruiser Hindenberg | |

|

The great High Seas Fleet, the bulk of whom had survived the violent contest at Jutland, and in the German view undefeated in battle, ultimately succumbed to self-inflicted wounds. Of the 74 ships imprisoned at Scapa Flow 52 were sunk; another 22 were beached by the British before going down. The beached vessels were soon refloated and distributed as war prizes among the various Allied navies, while those sunk were initially abandoned�decreed not worth the cost of salvage. Starting in 1922 however, salvage operations began that would ultimately raise 45 of the 52 ships scuttled�an amazing feat and story in itself. Today, there are seven complete wrecks remaining for divers to explore, as well as a number of debris fields left behind from the salvaged vessels. | |

|

|

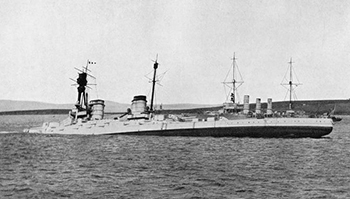

| Three of Germany's great dreadnoughts still sunk in Scapa Flow; (left-to-right) Kronprinz Wilhelm, Konig and Markgraf | |

|

|

|

|

| Scapa Flow's remaining cruisers (left-to-right): Coln, Dresden, Karlsruhe and Brummer | |||

|

|

|

|

| Scenes from aboard John Thornton's dive boat Karin | |||

|

Monday, September 9, 2019: This morning we dived the wreck of the cruiser Dresden. Lying on its port side, the ship is largely intact, although her main deck forward of the superstructure is peeling away from the hull and drapes down toward the sand like loose wallpaper peeling off a wall. Lying on the sand alongside her hull, the wreckage of her superstructure lies in scattered and sometimes recognizable heaps of steel. The armored fire control tower is prone on the bottom--a strange, roughly triangular structure that seems to defy recognition without a guide book to identify it. Beneath the curling deck plates are two capstans in place--one clearly recognizable and the other buried but for the gears and mechanisms that sat beneath the main deck. The bow itself seems nearly perfect, down to the coat-of-arms still in place beneath the gunwale. | |

|  |

|  |

| German cruiser Dresden today: divers swim over the ship's fire control tower (top left); Karen Flynn lights up the buried base of a bow capstan (top right); Mike Powell shines a light on the business end of a 15-cm gun barrel (bottom left); the breech end and turret remains of a 15-cm gun (bottom right) | |

|

"Swimming forward along the deck of the cruiser Dresden, Karen Flynn and I enter a long tunnel beneath the ship's drooping steel deck, hanging down like the skin of a peeling onion. Broken away from the upper gunwale, the now-curled deck forms a long steel tube reminiscent of a breaking wave; if we were surfers we'd be "riding the tube." We pass a cylindrical anchor capstan, still standing on the foredeck, just above the sea floor. Emerging from beneath the hanging deck we find ourselves at the ship's bow. There on the side of the hull, just aft of the gracefully curved stem, is the clear outline of a shield that bore the ship's coat of arms. Excitedly I point it out to Karen, who obligingly lights it up for me to photograph in the green depths." Tuesday, September 10: After finally getting a good night's sleep (jet lag can be a killer!), we dived one of Germany's massive dreadnoughts this morning: Kronprinz Wilhelm. Like all battleships, made top-heavy with the enormous weight of their big guns and thick armor plate, Kronprinz turned "turtle" when she sank, and lies upside-down on the seabed. The ship is so big that it seems impossible to comprehend the layout of the wreck in a single dive. The bottom of the hull is like a huge plain of steel plate, punctuated at irregular intervals by holes, recesses and twisted wreckage, some giving access to a cavernous interior. I find it difficult to comprehend what I am looking at, and even harder to find anything meaningful to photograph. | |

|  |

| Scenes of un-recognizable wreckage on and in the upturned hull of the dreadnought Kronprinz Wilhelm | |

|

That afternoon we dived the light cruiser Coln, one of the most intact shipwrecks in Scapa. Today she lies on her starboard side. The forward half of the ship seems largely undamaged, and a pair of capstans still protrude from the now-vertical foredeck. Further aft, the remains of her forward 15-cm gun turrets can be seen, the guns themselves missing as they were salvaged some time ago. The turrets now appear to have had their tops lopped-off by some huge knife, leaving their lower halves seemingly intact, including part of the square viewing ports on either side of the missing guns. | |

|  |

|  |

| The forward half of the German cruiser Coln: Karen Flynn and superstructure wreckage (top left); skylight forward of bridge structure (top right); Karen Flynn shines a light on one of the foredeck capstans (bottom left); the remains of the port side forward 15-cm gun turret, sans-gun (bottom right) | |

|

Wednesday-Thursday, September 11-12: The remnants of hurricane Dorian arrived in the Orkneys today, reminding me of another time a hurricane had followed me across the Atlantic. This morning the wind was blowing a solid 30+ knots, turning a 3-4 foot chop into a field of white spume. The wind would continue blowing for days, yet the diving went on uninterrupted in the stout North Sea dive boats, which barely rolled in the heavy winds. One morning we dived a mountain of steel lying on the seabed that was once the dreadnought Markgraf. Seeing a battleship lying inverted on the bottom of the Flow is a rather intimidating experience. The limited visibility, combined with the damage caused by 100 years of decay, make it difficult to figure out where you are on the sunken ship. I found myself scootering endlessly along one side of the wreck in search of the 5.9-inch casemate guns; only later did I realize I was on the wrong side of the wreck! With only one dive on the great ship for the week, there is no second chance for me to find these iconic guns, and I will have to await a return trip to this fascinating place. After leaving Scapa, I became obsessed with dreadnoughts and their history. I bought and read books. I dreamed of returning to Scapa to dive these magnificent wrecks again. I even bought a model kit of HMS Dreadnought, the ship that started a revolution in battleship design, and began a naval arms race. As we drove south from the ferry that brought us back to the Scottish mainland from the Orkney Islands, I began to formulate an idea for an article about dreadnoughts, and even began writing it on my phone. The article traces the brief but dramatic history of these ships, following both their history, and dives on their wreck sites, that I have had the priviledge of visiting over the years. | |

|

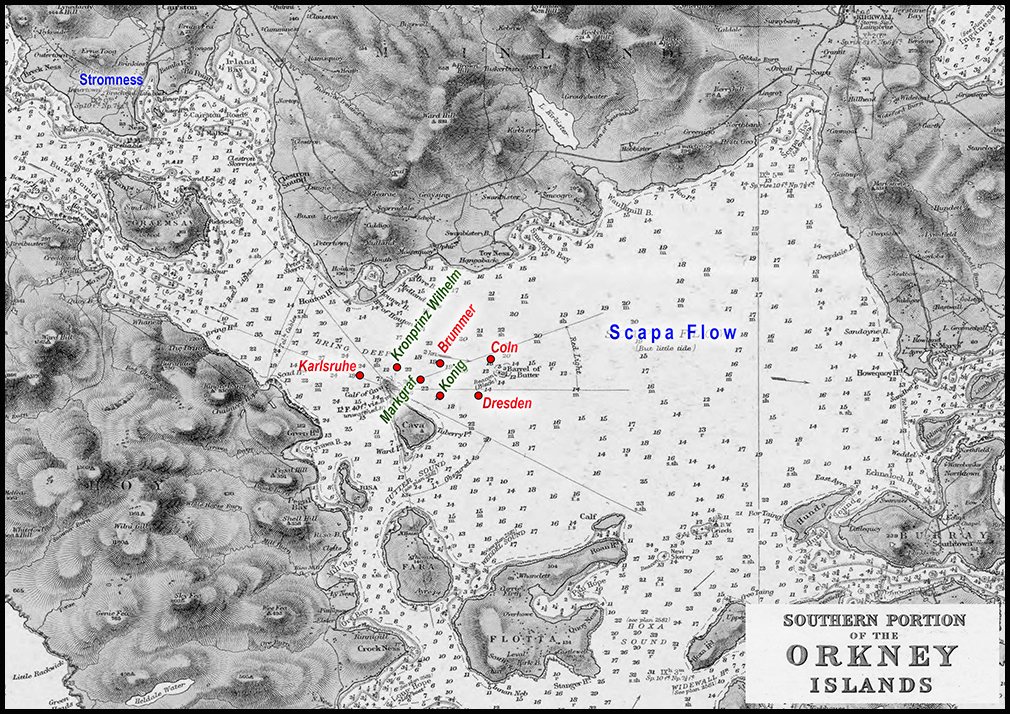

| Chart of the harbor at Scapa Flow, showing the approximate location of the remaining wrecks of the German High Seas Fleet |

|

| Moonlit night over Stromness and its Harbor |

|

| 1/350 scale model of HMS Dreadnought |

All images, text and content Copyright © Bradley Sheard. All rights reserved.