|

The Revenue Cutter Mohawk:

Silent Witness to an Environmental Debacle

This article was originally published in the October 1993 issue of New York Outdoors, and later in the October 1995 issue of Sport Diver magazine.

|

| USRCS Mohawk's aft gunmount |

Amidst a bubbling froth of escaping air and roiling sea water, a dying ship settles to the ocean bottom outside New York Harbor. Clouds of steam spew forth from the ship's stacks as cold sea water reaches her red-hot boilers; a last few gasps of air burst from her hull and claw their way towards the surface. Then all is still and quiet once again--another ship has been swallowed by the sea. The United States revenue cutter Mohawk, transferred to the Navy six months earlier on the day the America entered World War I, had become a victim of collision at sea on a foggy morning in October, 1917--run down by one of the very merchant ships she had been assigned to protect.

While the Mohawk's place in the history of World War I ended with her sinking, her rusting hull would survive to bear witness to one of man's greatest environmental debacles. Purely by chance, the Mohawk had come to rest in an area that years later would bear the mark "Dump Site: Municipal Sewage Sludge," on coastal navigation charts. The 6.5 square-mile rectangle designated for the disposal of man's most personal refuse lay twelve miles southeast of New York Harbor, and came into general use in 1924. The Mohawk lay just outside the northwest corner of this rectangle, and over the years her collapsing hull slowly disappeared under a rain of poisonous sewage sludge—a rain that would continue for more than six decades. Over the course of time marine life was slowly smothered, and the surrounding waters became known as "the dead sea" to fishermen and environmentalists.

As the turn of the century ushered in the industrial revolution, bringing mankind new-found productivity and filling his shop windows with a huge quantity of consumer goods, the alleys behind those same shops began to pile high with garbage. The disposal problem quickly became acute, and it didn't take long for man to look toward the sea as the perfect garbage depository. But the sea is neither bottomless nor endless, and soon after the dumping began the ocean was coughing up garbage along the seashore. Between 1925 and 1931, a controversy raged between the states of New York and New Jersey, the latter blaming the former for the trash washing up on its beaches. A court battle resulted which caused the end of garbage dumping at sea in 1934—yet the dumping of an even more treacherous substance continued unabated.

Ten years earlier a special site was designated for the disposal of "sewage sludge," twelve miles southeast of New York Harbor. Day after day, year after year, decade after decade the "sludge barges," a newly defined class of naval architecture, made their daily rounds to dispose of their cargo. The environmental awareness that came with the arrival of the '60s and '70s drew attention to this abhorrent practice. In 1973 Dr. William Harris, a Brooklyn College marine scientist, reported that a survey of the ocean bottom off Atlantic Beach, Long Island by graduate students had found sewage sludge that had crept to within one-half mile of the beach. Seven months later, he announced that the sludge had come to within one-quarter mile of the beach and predicted that the ocean currents would bring the sewage ashore by 1977. This was disputed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), who claimed that the sludge "presents no threat to swimmers and may even be of natural origin."

|

| Dead crabs and debris litter the darkened ocean bottom at the Mohawk's gravesite |

In June 1976, twenty miles of Fire Island beaches were closed to swimmers: the prediction of Dr. Harris had been off by only one year—the sludge had arrived early. Throughout the month of June "globules of sewage-like material" washed up along the Fire Island beaches. When accusing fingers pointed to the City of New York's dumping practices, the EPA came rushing to the defense of the metropolitan giant, denying that the City was the "major cause" of the polluted beaches.

In July, commercial fishermen reported a huge fish kill off the coast of New Jersey, extending from Sandy Hook to Barnegat Inlet; the water below the thermocline was fouled a yellowish-brown color and the oxygen content was found to be below normal. Biologists later determined that offshore sewage dumping had caused an algae bloom that depleted the sea water's dissolved oxygen and subsequently killed hundreds of thousands of fish. Raw sewage continued to wash up on the beaches, and public outcry was enormous. It was the uproar of the voting public that finally caught the attention of the politicians, who had so long ignored the environmentalists. In July the EPA announced that all municipalities must end ocean dumping by 1981; EPA administrator Gerald Hansler proclaimed that the government would "not tolerate" any failure by New York and New Jersey to meet the deadline. Such threats failed to impress the City of New York, however, who sued the EPA over the issue and won—Judge Abraham Sofaer ruled that the EPA could not stop New York from dumping its sludge in the ocean unless it determined that such dumping would "unreasonably degrade the marine environment." The dumping continued.

|

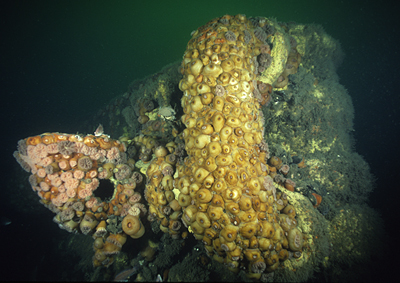

| The Mohawk's steam engine rises high above the ocean bottom, providing a platform for an oasis of life |

In 1985 the EPA tried a new approach by ordering the sludge to be dumped further out to sea: 106 miles off the New Jersey coast and beyond the edge of the continental shelf. The new dumping limits were to go into effect at the end of 1987 and compliance was all but assured when sewage again appeared on the beaches during the summer of 1987, this time accompanied by infectious medical waste. Dumping at the twelve-mile site ceased in November, but only at the expense of a previously untouched deep sea environment off the edge of the continental shelf. Before long, lobster fishermen reported that crabs and lobster caught in the area exhibited burn-like holes eaten through their shells by bacteria breeding in the sludge on the ocean floor.

The summer of 1988 brought another massive fish kill off the New Jersey coast and medical waste continued to wash ashore on the beaches, outraging a public fearful of the AIDS epidemic. While the source of the medical waste was unclear, the message wasn't. In October 1988, both the House of Representatives and the Senate passed a bill banning the dumping of sewage sludge at sea after January 1, 1992. New York City immediately protested and managed to gain a six-month extension of the deadline, but the end of ocean dumping was inevitable. On July 7, 1992, the sludge barge The Spring Creek released the last 450,000 cubic yards of sewage sludge to be dumped in United States waters. A long, hard-fought battle had finally been won.

But the end of 63 years of ocean dumping did not suddenly change the condition of the marine environment—the damage had been done and the recovery of the area would take time. Meanwhile, the forgotten wreck of the Mohawk had been rediscovered in the early seventies, first by fishermen and then by recreational scuba divers. The members of the "Aquarian Dive Club" were the first to visit the as-yet unidentified wreck in 1973, fifty-five years after her demise. But the dump site was still in active use at the time, and the divers were greeted by an inky-black maelstrom of sludge and sea water when they reached the ocean bottom—visibility was virtually zero. But these explorers were persistent, and later that summer they managed to recover a large bronze bell bearing the inscription:

U.S.R.C.

MOHAWK

1902

The Mohawk appeared to have risen from her grave. But unlike other local shipwrecks which had been transformed into lush artificial reef sites over the years, the Mohawk appeared dead and sterile. Sewage sludge, dumped for decades, had driven almost all living creatures from the area. Virtually no bottom-dwelling marine life could be seen on the wreck; what little marine life could be found was often found lying dead and lifeless amongst the Mohawk's scattered wreckage—only on the higher parts of the wreck did life exist in any quantity. Even there, away from the poisonous wastes of humanity which covered the bottom, the fish life appeared deformed and diseased.

A few years after the close of the twelve-mile dump site, however, an astounding change began to take place in the waters surrounding the wreck of the Mohawk. Visiting scuba divers found the murky, yellowish-brown water of years past less and less frequent. Fish and other marine life slowly began to return and, amazingly, over the course of several years a six-decade accumulation of sludge began to recede.

|

|

To the casual visitor, the wreck now appears similar to other shipwrecks in the area. Schools of fish swarm over the Mohawk's bow and stern, like clouds of gnats on a warm summer's day. Sea anemones carpet the sides of her hull, while crabs and starfish crawl slowly across the debris-littered bottom. The Mohawk's little steam engine rises some fifteen feet above the sand, a towering platform where a lush oasis of life has taken root. Flowering anemones festoon a maze of steam pipes and tubing, climbing the engine's side like ivy climbing a garden trellis, while bergals swim in and out of a maze of nooks and crannies. Another group of anemones, pristine and pure white, fight for habitat space on the yoke of a gun mount near the Mohawk's stern. Overhead loom the lonely ribs of her hull, the steel plating long ago rusted to atoms. A healthy variety of life seems to be flourishing on the wreck—so long as the exploration remains cursory.

Down below, close to the bottom, are signs that all is still not well. Plastic debris of decades past can be found intermingled with the carcasses of dead crabs and lobsters. Glass bottles from an earlier epoch in man's dumping history abound, along with evidence of more recent disposals—scores of medical hypodermic needles. Fanning the ocean bottom around the wreck quickly shatters the illusion that the sludge has completely disappeared; under the fine layer of brownish sediment lies a thick layer of black goo of unmistakable origin.

Very little live marine life can be found inhabiting the ocean floor, although this, too, is slowly changing with time. A few solitary starfish can now be found crawling slowly across the silty bottom, searching for sustenance—or perhaps a better existence. Many dead crabs, both body parts and entire animals, lie limp and lifeless amid wreckage from a decaying ship; a visitor can only wonder what brought about their death. Recently, bottom fish have begun to return to what was all too recently a forbidden world to them. It is chilling, however, to see such masters of camouflage as flounder and goosefish taking on the black coloration of a sludge-stained bottom. Perhaps this is a testimony to the magnificent range of their adaptability, but it is indeed a sad one.

A shipwreck represents a fascinating time capsule from a different age: a tiny microcosm plucked suddenly and without warning from the world—a frozen instant of time preserved while mankind marches ever onward. With passing years the sea's creatures take over and provide a living veil of camouflage, bringing new life to what has died. But here, within the Mohawk's world, an intruder has interfered with the process. A continuous rain of poison fell upon the ocean bottom for decades, preventing the marvelous genesis of life from establishing a foothold. Instead, a rein of death was perpetuated that has only recently been brought to an end. Now that this desecration of the coastal oceans has ceased, the long delayed transformation of dead ship into living reef has begun. In the Mohawk's case, the process is a slow one, but it appears to be well under way. Perhaps more than anything, the return of life to the Mohawk's grave illustrates the incredible tenacity of life on this planet, for if life can spring forth in this once dead sea, it can undoubtedly take root anywhere.

The ocean, from which all life once emerged, was never intended to be man's cesspool.

All images, text and content Copyright © Bradley Sheard. All rights reserved.