|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| |

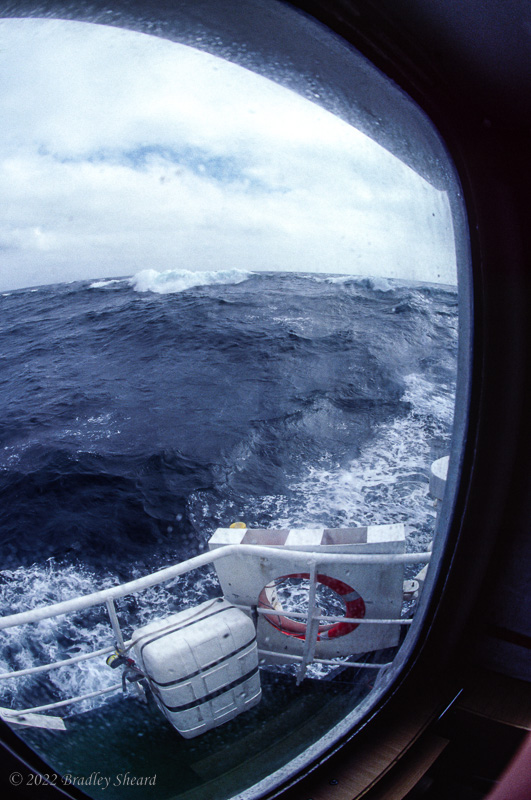

I just had to get out of this bunk, no matter how painful it might be. Like the other passengers on board I had been clinging to the bed boards of what seemed like my personal coffin for hours and desperately needed to escape. The 24-meter ex-Royal Navy tender Loyal Watcher was rolling heavily, beam-on to the fury of a Force 8 gale in the midst of the North Sea. As I made my way up to the Loyal Watcher's bridge, I found the skipper and captain alone. I gazed out the front windows in amazement as the huge waves rolled past at nearly eye level, despite the bridge being at least 20 feet above the ship's waterline. I longed for the seas of only two days ago, when this notorious body of water seemed like a glassy pond. Having seen the tormenting ocean first hand, and having snapped a few pictures for posterity, I staggered back below to the boredom, and relative comfort, of my bunk to ride out the remainder of this storm. This was day two of a scheduled twelve-day prizefight with the North Sea, and we were now running back to our corner, tail between our legs. By the time we finally reached the small fishing village of Thyboron on the West coast of Denmark, it was late at night. Despite the exhaustion of both crew and passengers—we had spent 15 hours battling our way back to port from the wreck site of the HMS Defence—it was all hands to the local pub to unwind. If such torture was the price of admission for exploring the remains of the greatest naval battle in history, it certainly seemed worth it. |

|

| |

|

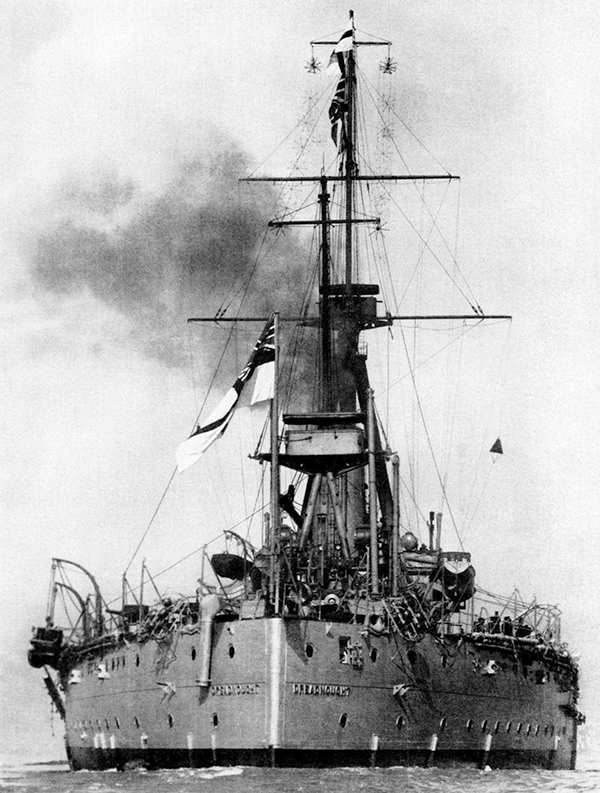

In the first decade of the twentieth century a ship was launched in England that changed both the face of naval warfare and the balance of power in Europe. HMS Dreadnought appeared distinctly different from all other battleships that preceded her, even to the casual observer. Five massive 12-inch, twin-gun turrets, and the near absence of secondary armament, was in stark contrast to the standard warship design of the day. Combined with her many other innovations the ship was so revolutionary that her launching instantly rendered the world's battle fleets obsolete—including England's own. HMS Dreadnought became symbolic of a naval arms race that followed, and her name became the descriptor for an entirely new class of battleship: henceforth, battleships were either "dreadnoughts" or "pre-dreadnoughts." Two major innovations set Dreadnought apart from all her predecessors: reciprocating steam engines had been replaced with steam turbines to achieve superior speed, and she had traded in nearly all of her secondary armament in order to carry a larger complement of big guns. The first change provided her with a maximum speed of 21 knots and the ability to maintain that speed for long periods of time; the second rendered her instantly superior in battle to any adversary then afloat. Before Dreadnought, battleships were equipped with a tiered arrangement of guns of varying sizes. Small and medium-caliber guns were placed within a "casemate"—an armored box placed midships and oriented to deliver coordinated broadsides reminiscent of the days of wooden warships firing iron shot; larger guns were placed in turrets forward and aft. But by their very nature, bigger guns had greater range, and the genius of Dreadnought's all-big gun configuration was that she could bring all her guns to bear on an enemy at superior range. In this new order of battle using big guns at long distances, the smaller guns of the pre-dreadnoughts would be useless. The ship with the greatest number of big guns could deliver more shell weight on target, at greater range and, at least on paper, was considered the de-facto victor even before the battle took place.  |

|

| HMS Dreadnought...the Ship that Started an Arms Race | |

|

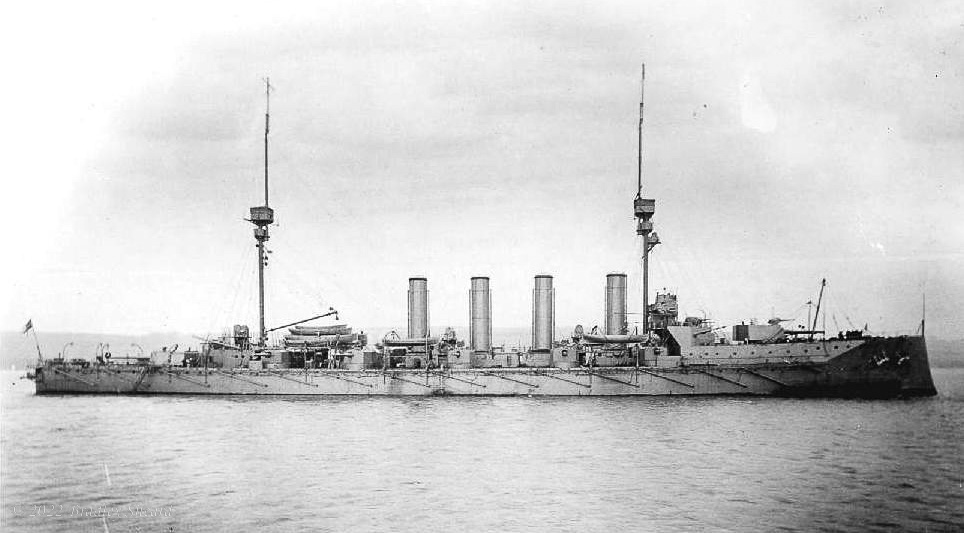

Precisely because Dreadnought was so revolutionary, she leveled the naval playing field among nations. Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II lusted for a powerful, world-class navy that could compete with England's—the launching of Dreadnought gave him a window of opportunity to achieve his dream. England's long-standing policy, being an island nation and dependent upon sea-borne trade, had been to possess a navy superior to the combined naval strength of the next two greatest sea powers, making her nearly un-challengable at sea. Since the Dreadnought rendered all fleets obsolete, the result was a naval arms race between Britain and Germany that was a large contributor to the causes of the First World War. Each nation sought to build bigger and more powerful warships than her rival, and each year the ships launched were armed with larger and larger guns. Huge steel barrels filled with massive charges of black powder propelled armor-piercing shells, weighing nearly one-half ton each, for distances of thousands of yards. Yet in one sense man's technology had outpaced itself, for these lethal machines were still aimed by optical means alone, despite the distances involved. The sophistication of radar to guide and aim these weapons would have to wait for the next war. | |

|

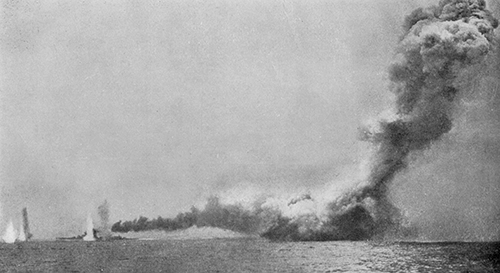

When war came to Europe, the world awaited--and expected--a titanic clash of the protagonist's dreadnoughts. But the battle was not quick in coming, for both sides were reluctant to risk an all-out confrontation of their great fleets. Such a battle could change the course of the war in short order. As Sir Winston Churchill put it from the British perspective, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, commander of the Grand Fleet, was "the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon." When the great contest finally did come, it involved some 250 warships and 100,000 men locked in a life or death struggle lasting barely twelve hours. After the smoke had cleared, the British had lost 14 ships and 6,094 men, while the German navy was 11 ships and 2551 men smaller. The German command knew they couldn't win an all-out, head-to-head battle with the superior British fleet, so they hatched a deceptive plan to draw the British fleet out in pieces and ambush it. The Germans split their fleet into two parts, sending the battlecruisers north under the command of Admiral Franz von Hipper, knowing that the British would get wind of the fleet movement and send Admiral Sir David Beatty's battlecruisers to intercept. The plan was for Hipper to then double back and lead the British to Admiral Reinhard Scheer's fleet of dreadnoughts following behind--an ambush designed to annihilate the British battlecruiser fleet. The plan had an escape clause built in--if the entire British fleet were to sortie, the Germans planned to quickly retreat and avoid a confrontation they would surely lose. In addition, the Germans stationed U-boats outside British naval bases in the hope that some of the enemies' warships could be torpedoed as they left port. Despite the carefully laid German plan, Britain dispatched not only her battlecruisers but the entire Grand Fleet in pursuit of the German ships. Because the British battleships and battlecruisers were based in different locations, the two fleets sailed separately, and the event unfolded with two groups of warships from each side headed for a rendevous with history in the North Sea. The first major encounter between the great fleets occurred between the two squadrons of battlecruisers. Each side knew that their own fleet of capital ships was quickly approaching from the rear, but were ignorant that the entire opposing fleet was also converging on the scene. As the battlecruisers opened fire upon one another, they turned and raced south at 25 knots--on parallel courses they traded deadly salvos as each desperately tried to destroy the other. Although the German ships in this initial encounter were outnumbered six to five, they had a visibility advantage and were outscoring the British in shells landed. Then the German Von der Tann hit the British battlecruiser Indefatigable with two 11-inch salvos and she began to go down. Another salvo of shells connected and there was a tremendous explosion--the Indefatigable disappeared in a cloud of smoke. 1,017 British sailors were gone in an instant. Four battleships from the main fleet then joined the five remaining British battlecruisers, clearly outnumbering the five German battlecruisers. Despite being outmatched, the German ships Derfflinger and Seydlitz concentrated their fire on the British battlecruiser Queen Mary, which had been damaged by previous hits. According to eyewitness accounts, three shells out of a salvo of four hit the Queen Mary, followed by a second salvo of two shells--a small puff of smoke was followed moments later by a deep red flame and a tremendous explosion. The ship split in two while the roofs of her gun turrets were flung at least 100 feet into the air. When the smoke cleared all that was left was the ships stern, her propellors still spinning. Another explosion followed and the great ship was gone, along with 1266 men. Looking on from the bridge of his flagship, Admiral Beatty reportedly exclaimed "There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today." | |

|  |

| The British Grand Fleet at Jutland | The end for HMS Queen Mary |

|

But the Germans were not yet finished with the British warships. The British armored cruiser HMS Defence fell victim to a hail of heavy gunfire from the German ships Lutzow, Grosser Kurfurst, Markgraf, Kronprinz and Kaiser. "Salvo after salvo from the German heavy guns fell at the shortest of regular intervals. . . In a moment the Defence was enveloped in columns of water from exploding shells. First aft, and then forward, immense flames gushed forth from under the turrets, and then the third of those tremendous catastrophes occurred which in this battle overtook only British ships. With an explosion audible in all the ships of both fleets, Defence flew in the air out of a crater of fire. Soon only a cloud of smoke hung over the water where previously there had been a ship, and no survivor bore witness to the way of her destruction." (Groos, Otto, Der Krieg zur See, 1914-1918: Der Krieg in der Nordsee, Bande I-V, Mittler and Sons, Berlin, 1925.) The German battlecruiser Lutzow was not yet done, however, and while under heavy attack let loose three salvos at the battlecruiser HMS Invincible--the last of which penetrated one of the main turrets, igniting the magazine below, and Invincible met the same fate as the Indefatigable and Queen Mary before her with the loss of another 1026 men. At this point the main force of the British fleet arrived on the scene ready to engage. The Germans immediately executed a 180-degree turn and attempted to run from the enemy's superior force. Fifteen minutes later Admiral Scheer came about again, trying to double-back behind the British ships; instead, he came face-to-face with the British fleet. The British ships opened fire and pounded the German's with salvo after salvo. A torpedo attack by German destroyers caused the British battleships to turn away in self-defense, and the bulk of the German fleet slipped away in the haze. Although there were fleeting encounters of the great ships during the ensuing night, including the loss of the German pre-dreadnought Pommern and the battlecruiser Lutzow, destroyer of the Invincible, the Battle of Jutland had effectively come to an end. It is inevitable that such a great battle have both a winner and a loser, but the outcome of Jutland has been the subject of much debate. Perhaps the fairest assessment is that the German's scored a tactical victory as they clearly sank more ships, but the British came away with a more important strategic victory. For the remainder of the war, the German High Seas Fleet remained in port, held impotent by the knowledge that it was outgunned by Britain's Grand Fleet. | |

|

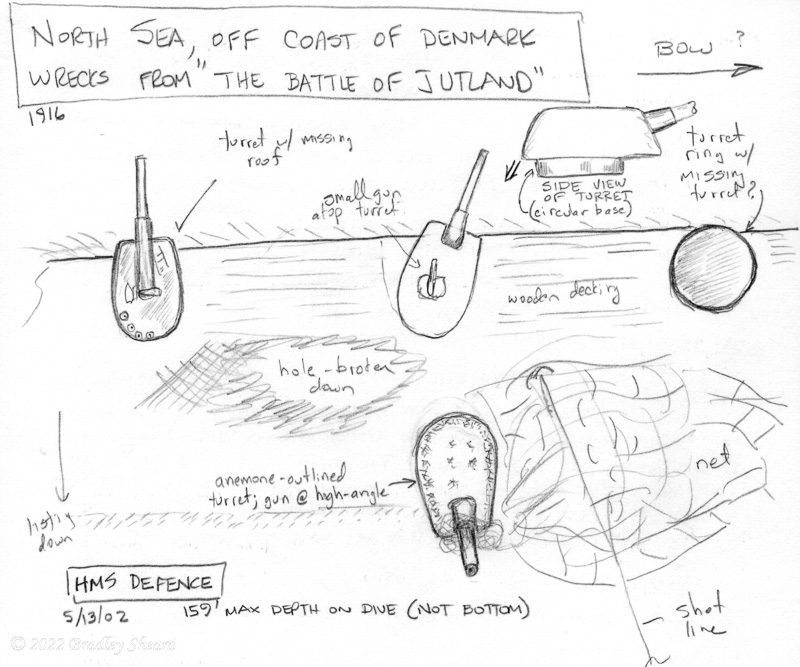

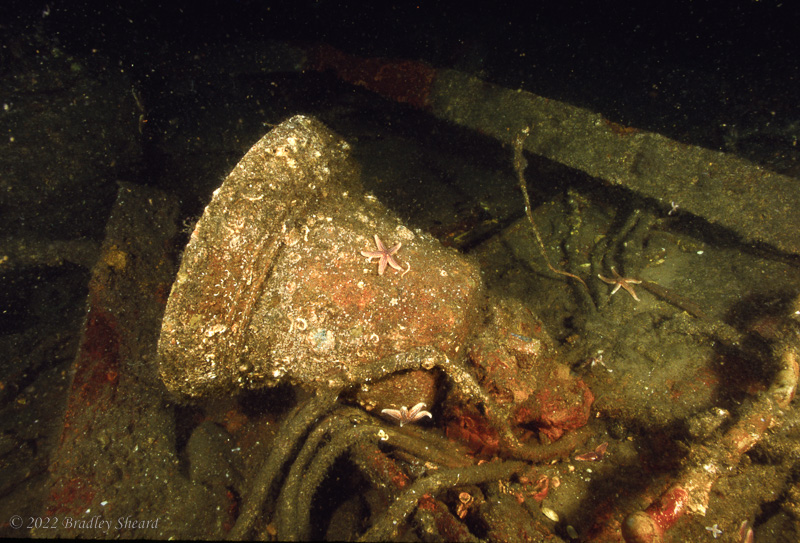

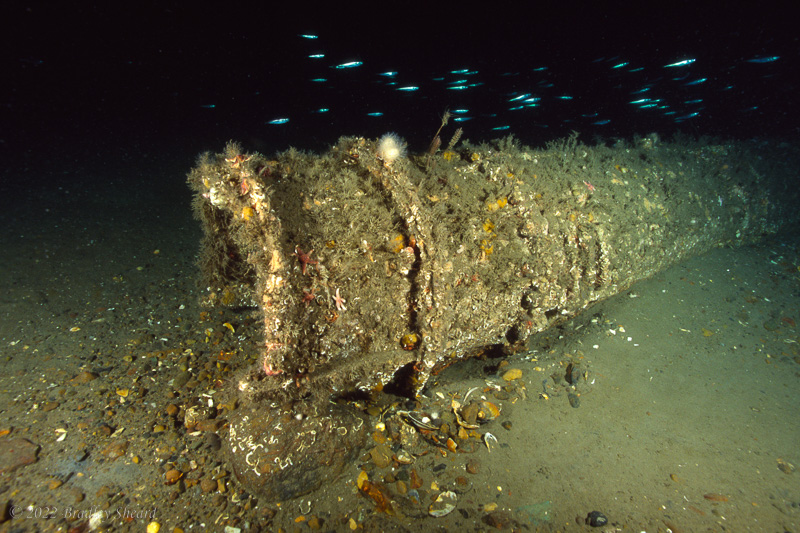

The Battle of Jutland took place nearly ninety-years ago (as of 2005), but the wrecks are not often visited due to their remote location and the fickle weather normally presented by the North Sea. Some of the wrecks are reportedly visited by Danish divers on occasion, and several of the wrecks were apparently commercially salvaged in the past. A 1992 Diver magazine article reports on an expedition to dive the wrecks in 1991, and the renowned British dive team Starfish Enterprise conducted exploratory trips in 2000 and 2001. I was fortunate enough to be invited on a trip run by British diver Chris Hutchinson aboard the Loyal Watcher in May of 2002; Mike Boring and I were the lone Americans on board along with many members of the Starfish Enterprise team. The trips to Jutland are truly exploratory trips. Many of the wrecks have not yet been dived or identified, and while I was there we were often diving a set of marks that to the best of our knowledge had not been dived previously. On this particular trip two bells were discovered, and one of the small wrecks was identified as the HMS Nomad by the inscription on her bell. Most of the trips are run as two week expeditions to ensure an adequate chance of securing a good weather window. Lying some 100 miles from the nearest land the wrecks are remote and weather becomes a serious concern. The area is foggy, often rough, and the water cold and deep--the trips are not for the faint of heart. In typical European wreck diving fashion, dive operations are conducted "live" using shot lines to mark and dive the wrecks, and the boat never anchors. A number of the British divers were concerned enough about drifting off from the dive boat and getting lost at sea--a sort of cold-water version of the film Open Water--that they bought and carried submersible EPIRBS. The water was an icy cold six degrees Celsius, and bottom times were largely limited by temperature rather than decompression tables. Note that taking artifacts here is prohibited--these are all considered war graves by the British government. Arriving in Thyboron, Denmark on the first day, we were greeted by the sight of flags standing out straight in a brisk breeze as if spelling out "Welcome to the North Sea". We had come a long way, however, and there were no dissenters when the skipper announced we would be leaving that night despite the questionable weather. Round one of this bout was about to begin with both fighters game and determined, and charging strongly from their corners to center ring. Round 1: The two fighters came out of their respective corners sizing each other up. The Loyal Watcher made a bold first strike out to the wreck of the HMS Defence, one of the furthest offshore of all the Jutland wrecks. The divers of Starship Enterprise, sponsers of the expedition, landed early blows by finding and shotting the wreck, then putting 12+ divers down on her remains. A previous expedition had dived a set of marks the year before and discovered HMS Defence. One side of the ship was reported to be upright and intact, with a line of gun turrets pointing outward in a menacing broadside along her gunwale. HMS Defence was an old-style armored cruiser that would be considered a pre-dreadnought were she a battleship. Sunk in an artillery exchange with the Lutzow, nine-hundred-three men had gone down with her. After dropping the shot line on the wreck, we descended 160 feet through dark but reasonably clear water to explore a visually magnificent shipwreck. That this was a warship was immediately obvious, for the shot line had fallen directly alongside the upturned barrel of a small gun turret. Indeed, an entire side of the ship stood upright and intact, with a line of small, single-gun turrets, still poised for action after 86 years of submersion. The roof of one of the turrets was gone, undoubtedly blown off during the intense action that led to her demise. The missing roof permitted a fascinating view inside the turret, complete with it's 7.5-inch gun. A projectile hung half-way out of the shell hoist running to the magazine below--clear evidence that she had gone down in the midst of battle. In the rear of the turret stood a neat row of shells, standing upright and ready for use. | |

| |

| HMS Defence (left); a sketch by the author of Defence's wreck (right) | |

| |

| A stack of dishes in the wreck's rubble field (left); HMS Defence's bell (right) | |

| |

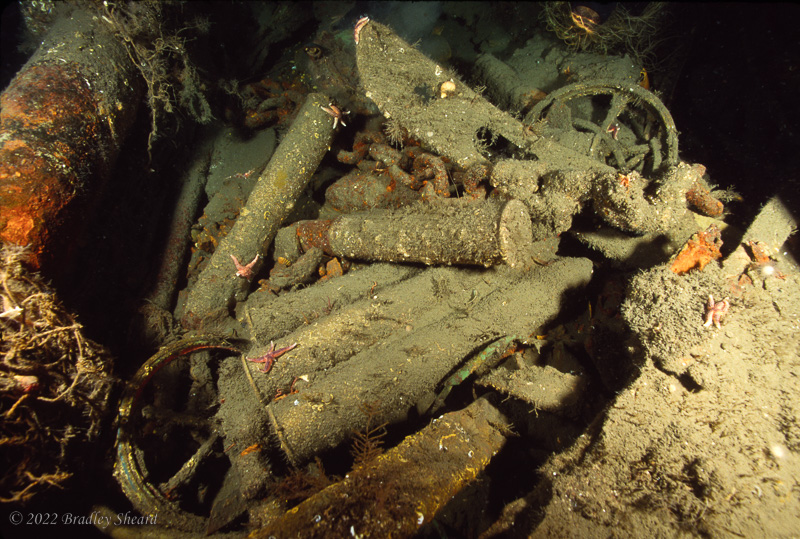

| Casemate guns still in place on the wreck | |

|

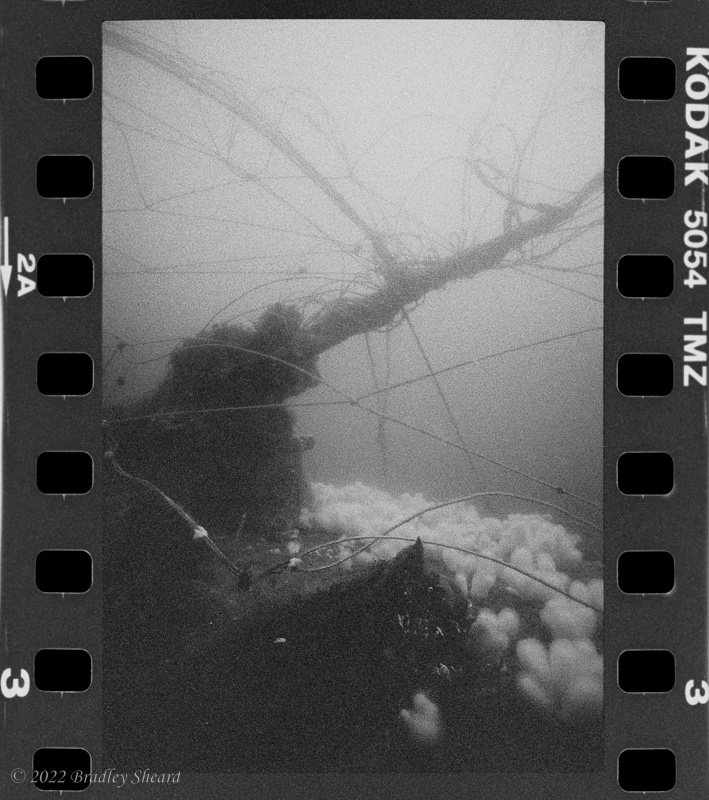

Round 2: Having pulled off a fantastic first dive of the expedition the divers were awarded round one of the bout. But the North Sea would not remain so docile in the second round and came out swinging at the sound of the bell. The North Sea soon delivered upon the divers a Force 8 gale, gleefully watching as the Loyal Watcher turned tail and made a torturous, 15-hour retreat to their corner in Thyboron. The North Sea had clearly taken round two of the match. Round 3: As the bell sounded for the opening of the third round of the fight, the North Sea quickly appears in the center of the ring, clearly agitated and dancing about with great showmanship, making taunting gestures at the Loyal Watcher's corner. Although well rested after a good night's sleep, the diverrs fail to emerge from their corner. The passengers and crew hang back warily after yesterday's late-round throbbing, carefully watching the North Sea's center-ring antics and waiting for an opening. Later in the day it became apparent that the Watcher's waiting game was paying off as the North Sea began to tire. The intrepid Loyal Watcher carefully made her way out to sea, ever watchful for any aggresive moves by her adversary. Round 3 awarded to the North Sea by forfeiture. Round 4 opened with the Loyal Watcher making a dramatic thrust deep into the North Sea to the wreck of the HMS Invincible. Invincible was one of three British battlecruisers that had met a violent end during the Jutland battle. The shot line brought us down alongside an intact, 12-inch gun turret with both guns in place but the entire turret roof missing. Two huge brass gun breeches glinted in the beam of our dive lights, continuously polished by the current-induced undulations of a trawl net draped over the turret. The massive barrels stretched out over the sea bed some twenty feet, and appeared still ready for action. The North Sea seemed content to bob, weave and feint, but she landed no blows and that afternoon the divers made a second dive on HMS Defence. Chris Hutchinson and Christina Campbell found the ship's bell on the dive, but it would prove to have no inscription and positive identification of the wreck was still elusive. | |

| |

| Mike Boring with the breech end of a 12-inch gun, HMS Invincible (left); gas cylinders inside the 12-inch gun turret (right) | |

|

Round 5: The North Sea entered Round 5 with yet another new tactic, as she put forth a combination of bright warm sunshine to soothe and distract the divers, while simultaneously serving up a brisk breeze and choppy seas. Clearly intended to put the divers off-balance, this new tactic was simply ignored as Loyal Watcher pressed on with her own agenda. The morning saw another dive on Defence, while the afternoon's dive was an exploration dive to a fresh set of as-yet unidentified numbers. This turned out to be one of the many German torpedo boats lost during the great battle. As the day wore on the North Sea once again began to tire and the seas steadily calmed. | |

|  |

| |

| Torpedo tube on German gunboat wreck (above left); shells and shell carriers (left, below); Mike Boring with mug inscribed "Bavaria" on bottom (right) | |

|

Round 6: The North Sea set forth from its corner this fine sunny morning and simply lay flat on its back, putting up no fight at all. The divers aboard Loyal Watcher took full advantage of their opponents passive behavior and mounted an all-out assault on the wreck of HMS Defence. Later in the day, with the North Sea still displaying disinterest in the diver's activities, yet another German torpedo boat was discovered. Badly broken up and clearly a small vessel, she was littered with shells and at least one torpedo tube. Mike Boring found a small ceramic mug amidst the wreckage with "Bavaria" inscrbed on the bottom--clearly another German casualty of the Battle of Jutland. Round 7:The North Sea continued its passive behavior this morning with a glassy sea and mild fog, sea birds rising and falling peacefully on an ever-so-slight ground swell. Taking advantage of the fine weather Loyal Watcher headed north to the location of another of the sunken trio of British battlecruisers: HMS Queen Mary. The deepest of any of the Jutland wrecks and the furthest north, the visibility was a spectacularly clear one-hundred feet. The upside-down hulk of Queen Mary is massive as shipwrecks go. From my journal: 'Although she is largely broken and twisted, her massive size is obvious. The steam turbines that once drove the ship lie exposed near the stern, and are visually impressive due to their size alone. Off to the starboard side lies the inverted hulk of one of her after 13.5-inch gun turrets--along with a smaller casemate gun somehow sitting smack in the middle of the larger upside-down turret. The explosive force that ripped this ship apart and deposited the smaller gun here must have been enormous. In the center of the wreck lies an exposed magazine, with 13.5-inch shells and powder kegs lying in a jumbled heap--impressive evidence of her once destructive firepower.' Round 8: The following morning found the great North Sea continuing its rope-a-dope tactics, although there were omonus signs that the sleeping giant might soon awaken; for two days now the weather forcasts have been warning of impending gales on the horizon. A morning dive was made on the Queen Mary's bow section. Once again we were treated to the sight of huge guns on the ocean bottom. One of the forward turrets sits upright but canted at an angle, with one of the huge gun barrels pointing skyward, while the other gun barrel is missing, although the breech end appears to be in place. Like so many of these turrets the roof is missing, giving clear access to the interior. Nearby are two gigantic turret foundation rings standing on end, like huge archways standing over a rubble-strewn bottom. The weather remained threatening and choppy all day, a sign of things to come. An afternoon dive was made on a small British destroyer not far from Queen Mary. The wreck had had previous vistors and was believed to be that of HMS Nestor. The wreck held a surprise, however, and revealed it when a bell was found inscribed with the name HMS Nomad instead! | |

|  |

| Mike Boring with one of HMS Queen Mary's small guns and armor belt | 13.5-inch shells and powder canisters bursting from Queen Mary's inverted hull |

|  |  |

| Bow 13.5-inch gun and turret | Massive turret barbette lying on its side (bow section) | Stern machinery wreckage |

|

Round 9: A surprise offensive thrust by the North Sea began around 3 am. After days of weather warnings that never seemed to materialize, the barometer began falling rapidly and the North Sea began to beat its chest furiously. She steadily worked the Loyal Watcher's body with short, stiff jabs. After a few hours of this the North Sea's intentions became clear: wear down its opponent while giving us the opportunity to withdraw to our corner and avoid the inevitable knockout blow. We took the merciful offer of escape and spent the better part of the day retreating to our corner in Thyboron to await the end of the North Sea's tantrums. Rounds 10-12: The North Sea continued dancing at mid-ring, the shrill whistle of the wind through the rigging howling throughout the next several days. The wind-whipped flags of local fishing boats alone were enough to intimidate the Watcher's crew, and she refused to leave her corner for the remaining rounds to continue the bout. Tallying up the score of the twelve-round contest between the Loyal Watcher and the North Sea found six rounds for each. It appears that when challenging the North Sea, the best one can hope for is a draw. | |

| |

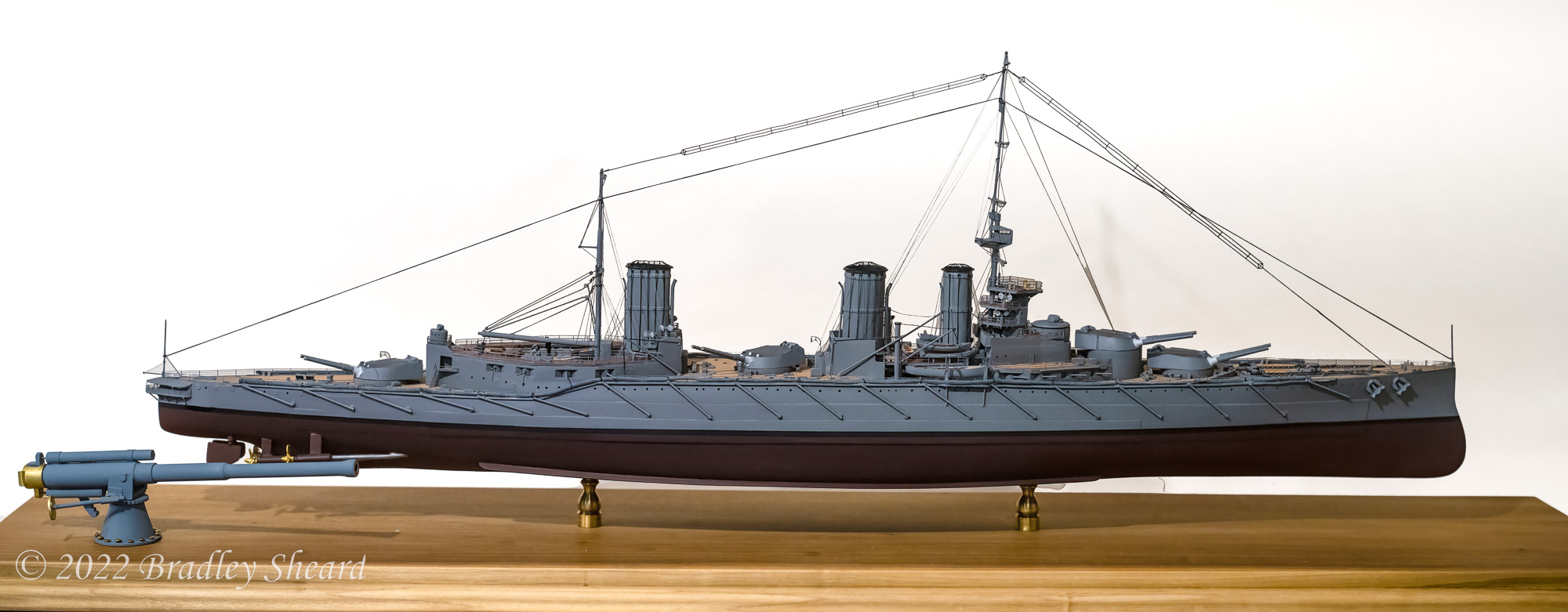

| A 1/350 scale model of HMS Queen Mary built by the author (from Iron Shipwrights kit) | |

|

Tarrant, V.E., Jutland: The German Perspective. Cassell Military Paperbacks, London: 1995. Hough, Richard, The Great War at Sea, 1914-1918. Oxford University Press, Oxford: 1986. Massie, Robert K., Dreadnought. Random House, New York: 1991. McCartney, Innes., Jutland 1916, The Archaeology of a Naval Battlefield. Conway, London: 2016. |

All images, text and content Copyright © Bradley Sheard. All rights reserved.