|

Ghostly Guns of Iron Bottom Sound

| |

| This article was originally published in the September/October 2011 issue of Scuba Diving Magazine | |

|

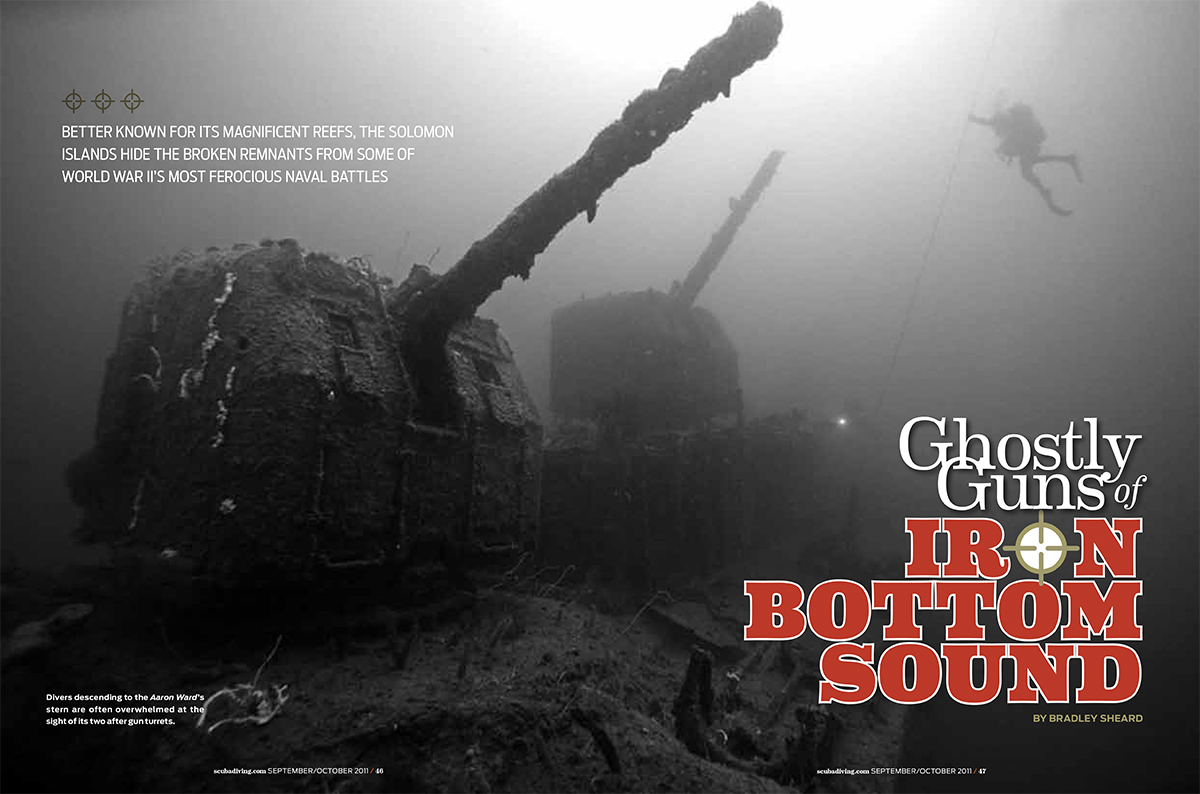

Descending slowly into the depths, I find myself freefalling through both space and time�200 feet down and 63 years into the past, to a time when the world was in violent conflict. Nearing the ocean bottom, I come face to face with the muzzles of two ghostly five-inch guns, still pointing skyward, locked in an eternal struggle with the aircraft that sent the USS Aaron Ward to her grave. The guns appear ready to fire at any moment, lacking only muzzle flashes to awaken them from their slumber. Dropping to the after deck, I swim around the ship's fantail, past empty depth charge racks, then drop over the port side to the sand for a peek at one of the Aaron Ward's sculptured, high-speed screws. In life, the twin-screwed destroyer was a heavily armed speed demon, capable of 37 knots flat-out, and it was these propellers that had driven her. Ascending to the deck and continuing forward, I spot the starboard 40mm Bofors antiaircraft gun. Although the mount has collapsed, the twin barrels, gunner's seat and elevation wheel are clearly visible�it was here that men sat and faced the Japanese dive-bombers during the Aaron Ward's final contest. The entire panorama is like a battlefield frozen in time, lacking only the human participants that once fought for their lives, and that of their ship. My heart pounds in my chest, adrenaline pumping, as I marvel at the scene laid out before me. I feel like a time-traveling spectator in a combat zone that now lies silently hidden beneath the waves�it is like touching history. | |

|  |

| Descending on the Aaron Ward's stern, a diver is greeted by dual 5-inch gun turrets still poised for action with the aircraft that sank the ship | The Aaron Ward's stern is bend upward, presumably caused by the ship hitting the bottom stern-first |

|  |  |

| The Aaron Ward is a fascinating window into history and beckons exploration. (left-to-right): Fallen gun director beneath bridge wreckage; searchlight iris with stack in background; fallen anti-aircraft gun and 5-inch gun on bow--note how both guns are pointing up toward the aircraft that sank the ship | ||

|

Further forward, a small tower draws my attention. As I rise to examine it, a tightly shuttered searchlight stares back at me, orange-encrusted vanes resembling the aperture blades of a giant camera. Ahead of the searchlight, the silhouette of the after-stack towers over the deck; beyond lies the entire forward section of the ship, begging to be explored. Time is short at this depth, however, and the rest of the wreck will have to wait for another dive. I turn and head aft again, swimming slowly along the starboard gunwale. I pause, suspended in a deep, colorless ocean 200 feet beneath the surface, mesmerized by the sight of the two five-inch turrets. Both guns point to starboard, each barrel at its own elevation, aimed at individual targets; the Ward is still poised for action after six decades at the bottom of the sea. As time ticks steadily away, I am forced to begin my ascent toward the surface and a long decompression. I back slowly up the mooring line, staring into the depths as the two turrets fade from view, thrilled to have enjoyed the privilege of this visit with history. | ||

| * * * | |

|

The Aaron Ward was the lure that had led me halfway around the world, to the island of Guadalcanal and a body of water so steeped in the history of World War II naval battles that its very name is synonymous with sunken ships. So many vessels were sunk in these waters that the sailors who lived through the savage contests that occurred here named the place "Iron Bottom Sound." More than 50 ships were lost here during the war, but with the Sound reaching depths of 3000 feet or more, most are beyond the reach of scuba divers. The shallow edges, however, hide plenty to capture divers' interest, as well as challenge their abilities. Japanese transports sunk right off the beach by the Cactus Airforce, floatplanes strafed by carrier aircraft during the invasion of the island and Allied warships sent to the bottom by Japanese counterattacks, as well as yet undiscovered wrecks, all beckon to be explored. | |

|

Although I had first heard of the Aaron Ward in 1996, it had taken me a full ten years to get here. While the Solomon Islands are a popular recreational dive destination, I was unable to find an operator willing to take me to a deep shipwreck like the Aaron Ward, until I found out about Neil Yates' Tulagi Dive operation. Neil first came here on holiday from Australia, dived "the Ward," met his future wife Yolande Jordaan, bought the business and built it into what is one of the top "technical" dive shops in the Pacific region. Fully equipped to support both open and closed circuit divers, he's personally made nearly 1000 dives on the Aaron Ward alone, not to mention nearly a dozen other local war wrecks. | |

|

The shipwrecks found here are not purpose-sunk artificial reefs, or merchantmen sunk in quick, one-sided carrier raids. Most of the ships lost in Iron Bottom Sound were front-line warships lost in savage gun and torpedo actions in the dark of night: brilliant searchlights illuminated the enemy, high explosive shells sailed through the night, ships exploded, and men died by the hundreds in encounters that lasted only minutes. The Aaron Ward was heavily damaged in one of these vicious battles in November 1942, absorbing nine direct hits, including 14-inch shells from a Japanese battleship. She managed to survive the contest and was quickly repaired and returned to service, only to fall victim to an aerial attack two months after Japanese ground forces admitted defeat and abandoned Guadalcanal. | |

|  |

|

The naval, land and air battles that took place around Guadalcanal are legendary in the history of World War II, and the island drips with history. Guadalcanal's strategic significance lay in a small airfield begun by the Japanese, and considered so dangerous to the supply lines between America and Australia that it warranted almost immediate invasion. Nineteen thousand marines easily took Guadalcanal and the surrounding islands during "Operation Watchtower" on August 7, 1942. Two nights later, a brief but deadly naval encounter sent the four Allied cruisers Canberra, Vincennes, Quincy and Astoria to the bottom. This stunning naval defeat prompted the US Navy to withdraw its warships and the half-unloaded transports, leaving the Marines behind, short on supplies, to finish and hold the airfield, which was completed only ten days after the invasion. Three days later the first Marine Corp fighter aircraft�the seeds of what became known as the Cactus Airforce�arrived at the newly anointed Henderson Field, named after one of the air heroes killed in the "Battle of Midway" two months earlier. What ensued was a bloody, sixth-month struggle between opposing land forces in a dank, malaria-infested jungle, fierce air battles between defending fighters and attacking bombers, all punctuated by intermittent but ferocious naval actions that left scores of broken ships hidden beneath tropical seas. | |

|  |

| The Kinugawa Maru's engine still juts above the surface of the sound | A motorcycle still in the hold of the Azumisan Maru, another sunken transport just off the Guadalcanal beach |

|

In the coming days I manage to explore a half-dozen more casualties of the brutal fighting that took place here. Two Japanese transports, the Kinugawa Maru and the Hirokawa Maru, were run onto the Guadalcanal beaches in the dead of night to re-supply Japanese ground forces; at dawn they were discovered by the Cactus Airforce and bombed into the depths. Today, the bows of both ships lie nearly on the beach, while their sterns sit in 85 and 190 feet of water, respectively. Both wrecks lie on the edge of a coconut grove only one-half mile apart, and are dived from the beach. | |

|  |

| Underwater scenes from inside the holds of the Japanese transport Hirokawa Maru, beached and bombed by the Cactus Airforce | |

|

One drizzly afternoon I get a chance to explore the Hirokawa Maru, the deeper and better preserved of the two transports. Walking into the water from the sandy beach, wearing twin tanks and donning fins in the shallows, feels alien after a week of diving the deeper wrecks by boat. Swimming quickly into the depths along the steeply sloping hull, I reach the ship's intact fantail, lying on its port side at 190 feet. Dropping to the sand, I find a heavily-encrusted deck gun pointing to starboard. Unlike the guns on the Aaron Ward, however, this cannon appears static and lifeless, as if its spirit had died long ago. The gun proved useless in defending the Hirokawa against the onslaught of the Cactus Airforce, whose planes bombed and strafed the ship for hours, leaving her a billowing inferno at the edge of the sea. | |

Leaving the stern behind, I begin my ascent. On this dive the ascent is not vertical, however, but a slow swim up the inclined hull toward the bow and the beach, marking the mid-point of the dive rather than its end. Along the way I explore empty, cavernous cargo holds. Each is a maze of structural beams, subdividing a gloomy darkness into tiny pockets of lightless space, once filled with desperately needed ammunition and supplies for starving Japanese soldiers locked in a losing battle. In the deeper holds, strangely twisted wire corals hang from overhead beams like tangled spaghetti, while finely filigreed coral bushes envelope deck fixtures, cloaking their form in a thicket of white. Further forward, giant H-shaped masts, once used to load supplies, jut out horizontally from the ship's deck like fallen goal posts. As the depth grows steadily shallower, the hull begins to crumble and lose form, but as its structure disappears it gains brilliance, for the shallows bring light, and with it life. Thick, rich coral has transformed a collapsing, rusting remnant of war into a living, breathing being. I find the stark contrast between the kaleidoscope of color found here, and the monochromatic depths of the Aaron Ward, just as striking as the distinction between the Ward's guns, alive and at action stations, and the Hirokawa's limp and lifeless stern gun. | |

| * * * | |

|

Sitting in Honiara days later, I gaze across Iron Bottom Sound, reflecting on my dives of the past nine days. A teeming afternoon rain has just ended and the water's surface is oily calm, marred only by the circular ripples left by the last few raindrops, while storm clouds still march steadily across the sea. I drift off into a dream world, my mind immersed in stories of combat I have only read about, and sunken battlefields I have now visited firsthand. Suddenly, a brilliant flash of light breaks the darkening twilight. The low-lying hulk of Savo Island stands out starkly on the horizon as the sky momentarily glows in brilliant gray relief. Seconds later, a deep rumbling thunder rolls across the sea as the luminous afterglow fades from the sky. Is there a lightning storm out there, or is it the sound of gunfire between great warships? There�another flash of light and the sky is on fire again�a lingering, unnatural incandescence that illuminates the scene of battle. I can almost see the Japanese cruisers, racing ahead at 26 knots, bearing down on the unknowing Allied cruiser force. Muzzles flash and eight-inch high-explosive shells rain down upon the American and Australian warships, while long lance torpedoes knife through the sea in a deadly fusillade. As the Japanese warships round Savo Island and speed off into the night, they leave behind an ebony gloom punctuated only by the glow of burning ships, all that remains to mark one of the worst Allied naval defeats of the war. As the lightning fades and silence descends upon the waters, I sit transfixed, unsure of what I have just witnessed. I feel as if I have awakened from a vivid yet implausible dream that my rational mind refuses to dismiss. And burned into my brain forever is the image of the Aaron Ward's guns, an apparition that will haunt me for weeks, months, even years, creating a visual manifestation of the sirens of legend whose call will only be answered by returning to see the Ward once again. | |

All images, text and content Copyright © Bradley Sheard. All rights reserved.