|

|

|

| HMS Dreadnought...the Ship that Started an Arms Race |

|

The outcome of the Battle of Jutland has been heavily debated for a century. While the British lost more ships and men than Germany, the High Seas Fleet spent the remainder of the war blockaded in port, only operating in the Baltic Sea and occasional brief excursions into the North Sea. Unwilling to risk another costly encounter with the Grand Fleet, Germany's surface navy was effectively an isolated, non-participant in the war. Thus the great clash of dreadnoughts has often been called a tactical victory for Germany, but a strategic victory for Britain. War continued to rage on the continent for another two and one-half years, however, and its end was perhaps as twisted and complicated as its beginnings. At the end of September 1918, the German army told Kaiser Wilhelm II that the military outlook was hopeless, causing Germany to seek a negotiated end to the conflict. A dizzying series of events followed, including the Kaiser's abdication, a revolt within the military and the proclamation of a German republic. An armistice between the two warring nations was finally signed in the early hours of November 11, 1918, taking effect at 11 am that same morning. Effectively a cease-fire agreement, three extensions were required before the Treaty of Versailles was finally signed on June 28 1919, officially ending the war. | |

|  |

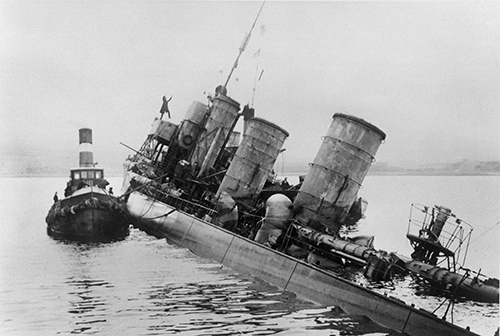

| The interned German fleet at Scapa Flow | German gunboat G-102 after the scuttling--she would be raised, only to be sunk by Billy Mitchell off the coast of Virginia in 1921 |

The terms of the armistice required Germany to surrender its entire fleet of U-boats, while the bulk of its surface fleet was disarmed and interred at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, north of Scotland. Manned by skeleton German crews and under the watchful eyes of the British Navy, the ships remained under German control while peace negotiations dragged on in Versailles, France for seven long months. When the terms of peace finally crystallized, Germany was given until June 21 1919 to sign the agreement. Admiral von Reuter, in command of the interned fleet, was isolated from home with no direct radio contact, and could only keep up with events through four-day old newspapers supplied by the British. Convinced the treaty would not be signed in time, and unaware that the deadline had been extended, he ordered his fleet scuttled on the morning of June 21, using pre-arranged signal flags flown over his flagship Emden. The great High Seas Fleet, the bulk of whom had survived the violent contest at Jutland, and in the German view undefeated in battle, ultimately succumbed to self-inflicted wounds. Of the 74 ships imprisoned at Scapa Flow 52 were sunk; another 22 were beached by the British before going down. The beached vessels were soon refloated and distributed as war prizes among the various Allied navies, while those sunk were initially abandoned�decreed not worth the cost of salvage. Starting in 1922 however, salvage operations began that would ultimately raise 45 of the 52 ships scuttled�an amazing feat and story in itself. Today, there are seven complete wrecks remaining for divers to explore, as well as a number of debris fields left behind from the salvaged vessels. | |

| * * * | |

|

September 2019: We came to Scapa Flow in September of the 100th anniversary year of the Great Scuttle; five Americans joined five Brits and two Germans aboard John Thornton's Karin. Typical of Orkney dive vessels, Karin is a stout, ex-North Sea fishing boat�as stable as they come. With six days of diving and seven major ships to explore, it proved a challenge to get a good sense of each wreck. There are three battleships and four cruisers left from the original 52 sunk, and all are visited regularly. The three dreadnoughts, Konig, Kronprinz Wilhelm and Markgraf, all lie upside-down, turned turtle while sinking by the enormous weight of their guns and armor. These massive dreadnoughts are so overwhelming it seems impossible to make heads-nor-tails of them in a single dive. The four cruisers, however: Coln, Dresden, Karlsruhe and the mine laying cruiser Brummer, all lie on their sides, and combined with their smaller size are a bit easier to navigate and understand. | |

|

Swimming forward along the deck of the cruiser Dresden, Karen Flynn and I enter a long tunnel beneath the ship's drooping steel deck, hanging down like the skin of a peeling onion. Broken away from the upper gunwale, the now-curled deck forms a long steel tube reminiscent of a breaking wave; if we were surfers we'd be "riding the tube." We pass the lower cylindrical anchor capstan, still standing on the foredeck, just above the sea floor. Emerging from beneath the hanging deck we find ourselves at the ship's bow. There on the side of the hull, just aft of the gracefully curved stem, is the clear outline of a shield that bore the ship's coat of arms. Excitedly I point it out to Karen, who obligingly lights it up for me to photograph in the green depths. A few days later the remnants of hurricane Dorian arrived in the Orkneys, reminding me of another time a hurricane had followed me across the Atlantic. This morning the wind was blowing a solid 30+ knots, turning a 3-4 foot chop into a field of white spume. The wind would continue blowing for days, yet the diving went on uninterrupted in the stout North Sea boats, which barely rolled in the heavy winds. Swimming along the deck of the cruiser Brummer, we come across a remarkable searchlight iris�to me it looks like the innards of a gigantic brass camera lens. Near the stern, two 5.9-inch single gun turrets have fallen from the deck, and now lie prone in the silt, beneath steel plating that has collapsed from above. That morning we had dived perhaps the premier wreck in Scapa�the dreadnought Markgraf. Seeing a battleship lying inverted on the bottom of the Flow is a rather intimidating experience�a gigantic mountain of steel towering over the sea floor and rising into the green gloom. The limited visibility, combined with the damage caused by 100 years of decay, make it difficult to figure out where you are on the sunken ship. I found myself scootering endlessly along one side of the wreck in search of the 5.9-inch casemate guns; only later do I realize I was on the wrong side of the wreck�how disappointing! With only one dive on the great ship for the week, there is no second chance for me to find these iconic guns, and I will have to await a return trip to this fascinating place. |

|

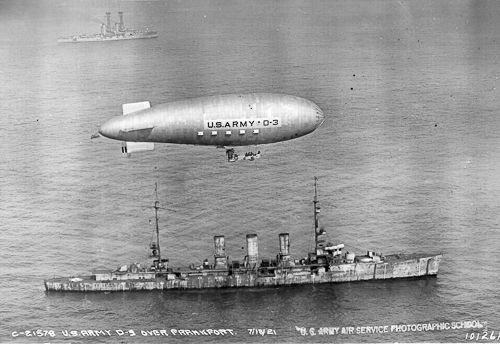

Just as Dreadnought had rendered its predecessors inferior, so its brethren were destined for obsolescence by the next wave of technology�the airplane. While the great battleships would see slow and continuous improvements through the next world war, they would never again hold sway and project pure power like they did at Jutland. The Great War had seen the introduction of many new weapons, and while the airplane had seen only limited use over the skies of Europe, its revolutionary impact on warfare was imminent. The all-big-gun dreadnought had become the backbone of the navy, and it would take someone from outside the naval hierarchy to see that the future lay in air power. In America, that man was Army Brigadier General William "Billy" Mitchell. A commander of air combat units on the front lines of Europe during the war, he had become a true believer in the future of the airplane. A flamboyant publicity hound, Mitchell took his case to the American public through the press after the military bureaucracy tried to ignore him. One of Mitchell's favorite tactics was to point out that a thousand bombers could be purchased for the price of a single battleship, and that his tiny airplanes could sink any naval vessel afloat. Testifying before a House Naval Affairs Committee in January 1921, General Mitchell issued a challenge for a demonstration: "Give us the warships to attack and come and watch it." That summer, against the protests of the United States Navy, Mitchell was given his targets: eight ex-German warships, some veterans of Jutland and the Scapa Flow scuttle, to be used for aerial bombardment tests 50 miles off the Virginia coast. | |

|  |

|  |

| Victims of the Billy Mitchell bombing demonstrations: (top row) German submarine U-117 and gunboat G-102; (bottom row) cruiser Frankfurt and dreadnought Ostfriesland | |

|

The tests began in June 1921, and the first target was the submarine U-117, a long-range minelayer that had sunk 23 ships off the American coast during the war. After two bombing runs the submarine broke in two and was gone. Three weeks later the target was the torpedo boat G-102. A veteran of both Jutland and the Scuttle at Scapa, G-102's decks were raked with machine gun fire before she too was quickly dispatched with 600-pound bombs. Three days later the fliers faced a more formidable target in the light cruiser Frankfurt. A veteran of both Jutland and the Scuttle in the Orkneys, the first runs over the target did mostly superficial damage, but when Mitchell's big bombers arrived carrying 600-pounders, what followed was hell falling from the heavens for Frankfurt. Huge columns of water shot skyward as the big bombs fell alongside the cruiser. One bomb blew a hole in her forward hull, and the cruiser began to go down by the bow. Settling on an even keel with her masts still standing, she finally pitched forward and disappeared. Somewhat alarmed, naval officials insisted there was no way that Mitchell's warriors could sink the heavily armored Ostfriesland. The great dreadnought had taken 18 direct hits at Jutland and hit a mine on the way home, yet still returned to port under her own power, without even losing her place in line�clearly a tough ship. To the Navy she was nearly unsinkable; to Mitchell, she would be the coup-de-grace of his demonstration, and he desperately wanted to bury the ship. The long awaited contest, airplane versus dreadnought, finally began on July 20. The first day brought bombardment with 250 and 600-pound bombs, but little damage was observed. At dawn the following day, however, it was clear that Ostfriesland was taking on water. That morning 1,100 pound bombs were dropped, but the end began when seven bombers arrived over the target carrying 2,000-pound bombs. The first fell alongside Ostfriesland's hull, producing a huge geyser of water; the second missed, but the third was a direct hit on the ship's bow, blowing a huge hole in her hull. Smoke billowed over the target; a fourth bomb, dropped alongside the ship, threw up a huge geyser, visibly lifting the ship. Bomb number five hit near the ship's stern, followed by number six: the bow pointed higher and the great ship began to roll over on her port side, settling rapidly. The seventh and final bomb was dropped in the center of the debris field left behind by the sinking ship, driving home the lesson of Mitchell's demonstration. The mighty Ostfriesland, veteran of Jutland, had gone down at the hands of a flock of tiny aircraft in only twenty-one minutes. It was a triumphant moment for Mitchell, and a crippling blow for the Navy. Admirals reportedly wept openly at the sight of the great dreadnought going down, and the Chief of Army Ordnance said, "A bomb has been fired today that will be heard around the world." A new era had been ushered in�the age of the airplane. | |

| * * * | |

|

When Ken Clayton was a child, he was fascinated by air power. A voracious reader, he pored over vivid accounts of General Mitchell's bombing tests in a book called Victory Through Air Power. The images of the sinking Ostfriesland stuck in Ken's mind for more than 30 years, resurfacing when he took up scuba diving. Ken then teamed up with Gary Gentile to find and dive the sunken dreadnought, and after that was accomplished, he followed up by finding and diving all eight of the German ships off the Virginia coast�wrecks that came to be known as the "Billy Mitchell wrecks." | |

|

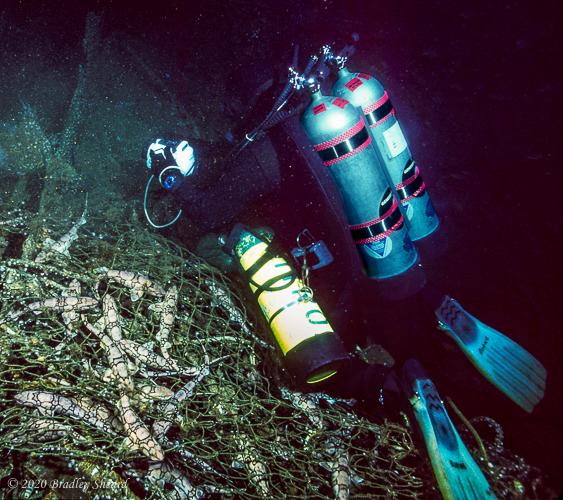

October 1994: Four of us stood on the deck of Miss Lindsey, anchored over the German light cruiser Frankfurt. For Ken Clayton and Harvey Storke, it was a return trip; for Mike Boring and myself, it was a frightening inauguration into ultra-deep open-circuit diving, before the widespread availability of rebreathers. A glimpse is all we would be permitted�the 400-foot (122 meter) dive plan called for only five minutes on the bottom, followed by 2-1/2 hours of decompression. Mike and I would attempt to document the dive on film: Mike was carrying a video camera, while I carried a still camera and strobes. As events unfolded, Mike's video camera imploded at a depth of 380 feet (117 meters), just shy of the wreck�so much for the video! | |

| |

| Mike Boring, surrounded by sharks, lands on the Frankfurt's deck with an imploded video camera housing | |

|  |

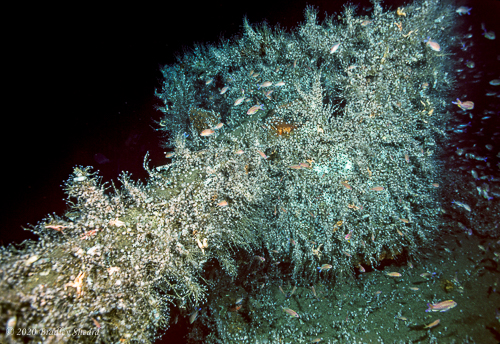

| One of Frankfurt's 15 cm gun turrets before bombing tests | 15cm gun turret on Frankfurt's deck during the author's dive in 1994 |

|

Silent and largely forgotten, Frankfurt sits upright on the ocean bottom, a mirror image of how she went down. Her tall masts tower above her submerged decks. Guns protrude from tiny, lone turrets along her gunwales, aimed at unseen enemies in the darkness of the deep ocean. It is a place few have ever visited. Trawl nets lie draped across her decks, enshrouding the ship's masts in a ghostly, now living, veil, forming an ironic nesting ground for the mysterious chain dogfish. Their tiny egg cases hang from nets and gun barrels like embryonic garland decorating a Christmas tree. Long-limbed, bright orange crabs crawl along gun barrels, which are in turn covered with a strange filigree of marine flora. Brightly colored schools of small fish swarm over her decks and gun turrets. High overhead, a faint but deep green glow silhouettes the warship's giant mast, reaching upward toward the surface some 100 feet above her collapsing decks. It is truly another world�perhaps a world humans were not meant to visit. As we slowly ascend up the anchor line, gazing behind us into the dark and gloomy depths below, the outline of her hull slowly fades from view. Rising alongside her majestic mast we marvel at the incredible scene we have just witnessed. As we leave the last glimpse of her behind and turn our attention to our long ascent, a glance at our depth gages tells us we are still at a depth of 300 feet�a potent reminder of the inhospitable world we have dared to venture into. | |

| * * * | |

|

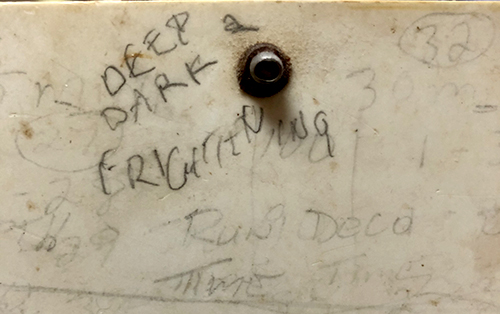

June 1992: My first descent to the dreadnought Ostfriesland was with Steve Gatto and Tom Packer. Breathing 12% heliox, we landed on the ship's bilge keel in near pitch-blackness at a depth of 338 feet (103 meters). I (foolishly) thought I could photograph the wreck in ambient light, and had loaded my camera with Kodak Tmax 3200 black & white film (which I push-processed to ASA 25,000). I clearly remember kneeling in the dark on the ship's up-turned hull, staring at my new digital depth gage and thinking over and over to myself�what the hell am I doing here? After a mere 7 minutes on the bottom we began our ascent and nearly three hours of decompression; at one point I scribbled on Tom Packer's slate "deep, dark and frightening," which seemed to sum up my impression of Ostfriesland. | |

|  |

| Sitting on top of Ostfriesland's hull at 338 feet in 1992 | Tom Packer's slate (he saved it all these years!) |

|

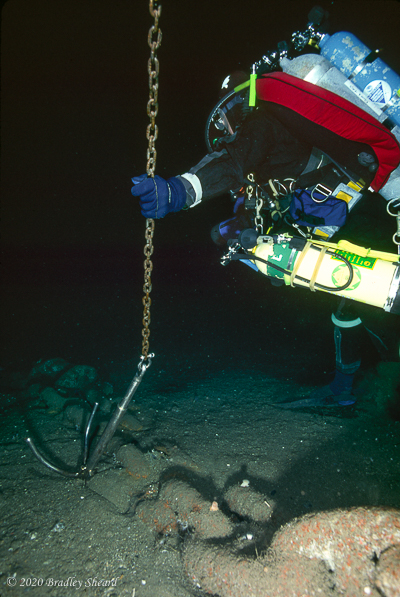

Four years later I found myself aboard Miss Lindsey again, headed offshore for another attempt at the iconic dreadnought. This time I loaded my camera with color slide film and dragged two big strobes along, bringing my own light source to the dark wreck. Diving with Ken Clayton, we descended Miss Lindsey's anchor line to the bottom at 383 feet (117 meters), only to find one tine of the grapnel hooked into the huge links of the battleship's anchor chain. The chain stretched across the ocean bottom in two directions for as far as our lights could see; surely Ostfriesland lay at one end of the chain�but in which direction? I could almost convince myself that there was a shadow in one direction, but at this depth there was little time to go swimming in search of the wreck, and after taking a few photographs of Ken and the anchor chain, we started our long ascent. Once again my efforts at photographing the wreck had been foiled. | |

|  |

| Anchor chain on the Ostfriesland's foredeck | Ken Clayton at the bottom of the Miss Lindsey's shot line... |

| * * * | |

|

The rise and fall of the dreadnought battleship was a short-lived affair. Begun with the launching of HMS Dreadnought in 1906, the end of their reign was definitively signaled by the 1921 bombing demonstrations off the American coast. In that short 15-year period, the British had built 35 dreadnoughts, while the Germans added 19 to their great fleet, and most other navies had joined in the building spree. Rendering all other battleships obsolete, they themselves were quickly eclipsed by the advent of air power. Perhaps the great dreadnoughts were more symbols of power than actual manifestations of power, but the future of warfare clearly belonged to the airplane. | |

All images, text and content Copyright © Bradley Sheard. All rights reserved.