|

The Creatures in the Boiler Tubes

This article was originally published in the August 1995 issue of Sport Diver magazine.

Shipwrecks are fascinating things. Whether they consist of broken and twisted steel hulls, buried conglomerations of oak timbers and copper spikes or rich caches of ancient pottery and gold coins, each shipwreck has a unique personality. Rich with history, their tales have been told in countless books and stories—accounts of stout vessels smashed on uncharted reefs or victims of wartime plunder; frail ships hopelessly outmatched by the fury of a violent winter gale and heroic epics of human suffering ending in both death and survival. Such stories of calamity seem to fascinate humankind—undoubtedly for many reasons. As simple adventure stories, they provide a safe escape from the monotonous existence of every day life by allowing us to live out an exciting event vicariously, but without the danger that makes them so exciting.

|

As captivating as these true-life narratives are to the armchair adventurer, the story of most shipwrecks has not yet ended. As each ship dies its own death, it comes to rest on an ocean floor that is largely a barren, featureless plain, only dotted intermittently with flowering oases of life. In this undersea desert, any obstruction becomes an attraction where the ocean's inhabitants congregate. The rusting steel hull of a sunken tanker or freighter provides the perfect platform for the development of a living reef. Fish are usually the first to arrive at a new wreck, but are quickly followed by scores of other creatures. Many species need a foothold or place to hide in the fish-eat-fish world beneath the sea, and ships by their very nature contain a myriad of nooks and crannies that provide perfect homes for many of these critters. As the years pass and more and more species take up residence, what was once a rusting steel hulk is transformed into a fantastic garden of life. Over time, the hard edges of a broken hull are everywhere softened by an encrustation of life—in colors both brilliant and subdued, the sea lends its delicate touch to a progressing work of art. What was once a ship has become a living reef that we term "artificial" only because its seed was a man-made object.

|

While the ocean bottom is littered with wrecks of many types from all eras, it was the advent of iron and steel-hulled steamships that led to the creation of shipwrecks that would stand the test of time. Once abandoned to the ocean a wooden ship rapidly rots and collapses, quickly becoming a scattering of half-buried timbers occasionally marked by a pile of ballast stones. But a steel vessel maintains a high profile on the ocean floor for a much longer period of time. While more often than not a steamer's hull eventually collapses upon itself like a house of cards, her heavily constructed propulsive machinery invariably stands tall for a century or more. Indeed, it is often the steam engine and boilers that are first picked up on a depth recorder when searching for a wreck site, and this machinery is one of the most distinctive features of a steamship wreck. The huge cylindrical shape of a ship's boiler can be an awe inspiring sight, but it also deserves a closer look by exploring divers, for it forms one of the most fascinating marine habitats found on a shipwreck.

|

| A tiny lobster in a boiler off New York |

In its simplest form, a boiler is a big iron box used to heat water and create high pressure steam. It is the steam pressure that provides the power to run a ship's engines—much as the high pressure air in a scuba cylinder can be used to do work with a pneumatic tool. Boiling water in an enclosed space produces pressure because water changing from liquid into gas (steam) wants to expand—but since it is trapped in a closed space, it can't. A whistling tea pot is a good example of the phenomenon—the "whistling" noise is produced by expanding steam escaping through the narrow opening in the kettle's top. It was this principal that allowed the replacement of wind powered ships by those burning coal.

As the design of marine power plants developed during the second half of the nineteenth century, boiler design grew more sophisticated. Ship designers required higher steam pressures in order to provide more efficient engines. In order to achieve those higher pressures, boilers changed from simple box-like structures into the more familiar cylindrical marine boiler—known as a "Scotch" boiler. A cylinder is a much more efficient shape for a pressure vessel than a flat-sided box, and allows the development of higher steam pressures without causing the boiler to burst. The lower half of a cylindrical boiler usually contained between two and four furnaces, where coal-stoked fires burned to heat water inside the boiler and change it into steam. It was soon discovered that additional heat energy could be drawn from the hot furnace gases that were a by-product of the coal fires. This was accomplished by venting the hot gas through a series of small tubes that passed back through the boiler before being exhausted out the familiar ship's smoke stack. These tubes can usually be seen on the flat ends of a cylindrical boiler, about midway up the face and above the large cylindrical furnace openings.

|

| Juvenile eelpout on the "Yankee" wreck off Long Island |

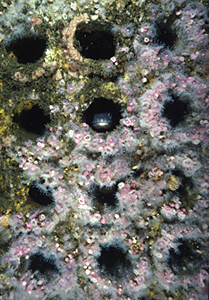

It is these "fire tubes," as they are sometimes called, that today provide a fascinating marine habitat on many old steamships. Forming a honeycomb-like structure much like a beehive, these banks of boiler tubes amount to an underwater apartment complex for a wide variety of fish and invertebrate life. Measuring two to four inches in diameter, each tube is the perfect size for a small animal or fish. In many ways they are reminiscent of the apartment-like bird houses sometimes erected for purple martins, with each individual boiler tube serving as a home for a tiny, individual animal. I first noticed this wonderful adaptation of an old boiler off the coast of North Carolina several years ago. With the weather too rough to trek out to one of the offshore wrecks, we spent the day diving a tiny Civil War era wreck subsequently identified as the Nevada. Since the wreck was small there wasn't very much exploring to do—until I noticed all the critters living in the old square box-boiler.

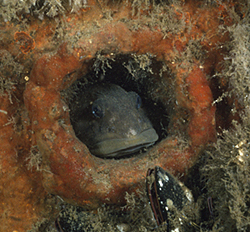

North Carolina's Outer Banks are bathed in clear, warm Gulf Stream water that supports a rich variety of life commonly seen on Caribbean reefs. Here in the Nevada's boiler I found tiny arrow crabs standing on long, stilt-like legs, guarding the "doorway" to their homes. Next-door, thick-tentacled sea anemones were filter feeding on passing nutrients, while tiny tropical fish schooled by outside. After this experience, I found myself stopping to examine the boilers on almost every shipwreck I dived. I soon discovered that many of the wrecks off the Carolina coast had boilers with very few, if any, "vacancies." Sea urchins, their long black, needle-like spines waving gently in the current grazed across the face of many boilers, while a closer look revealed tiny blennies darting from boiler tube to boiler tube, unable to decide which "house" they preferred. Sometimes I found colorful coral shrimp hiding shyly just inside a carefully chosen abode, only daring to venture outside under cover of darkness. Juvenile toad fish are another frequent inhabitant of these boiler tube apartments, and their ugly head and broad lips can often be seen protruding from their homes, sinister eyes peering angrily out at the surrounding community.

|

| Coral shrimp hiding in a tube off the coast of Virginia |

I also began to notice that these fantastic communities were not limited to the warm southern waters off the Carolinas. North of Cape Hatteras the Gulf Stream current moves further offshore and is replaced by colder water from the Labrador current. This cold water supports an entirely different cast of characters, but an inquisitive diver can still find thriving communities living in many an old boiler. Rock crabs are common in northern waters, and the juveniles of the species can often be found nestled snugly inside the round tubes perforating the flat end of a boiler. Another northern crustacean, the delicious lobster, would seem too large to establish residence in the tiny fire tubes of a boiler, but the smallest juveniles can be found living here as well. As do adult lobsters, the youngsters occupy their little caverns with just their claws and perhaps an antenna hanging out for observant passers-by to see. Sea anemones are perhaps the most common invertebrate animal living on northern shipwrecks, and while they invariably carpet the exterior of almost all shipwrecks, solitary animals can frequently be seen living inside boiler tubes as well. "Next-door" might be a baby ocean pout, its expressionless face, punctuated by fat lips and a long sloping forehead, peering out at his surroundings. The face of the boiler itself is often decorated with a rich veil of marine growth that would do justice to any decorator, ranging from yellow and orange sponges to pink or purple soft corals.

Each of these old ship's boilers supports an inter-related and complex community of animals that is often missed by visiting wreck divers. Overwhelmed by the magnificent vista and rich history of a sunken ship, they often dart from place to place trying to "see it all." But in your haste to explore be careful not to miss the trees for the forest, and take a closer look at that rusty old boiler the next time you're exploring that favorite shipwreck.

All images, text and content Copyright © Bradley Sheard. All rights reserved.